Chapter 11: faraway places

Most of the relatives and friends of the missing passengers and crew lived in England, where there was a long delay on news from the Torres Strait. The letters they have left behind reveal the unwavering hope and deepening despair that inevitably follow in the wake of those who fail to make it home.

One of those relatives was William Bayley. Having received the two oldest D’Oyly boys into his home he had ensured they got a good education, sending them – in accordance with their mother’s wishes – to a private boarding school, that of a Dr Ferminger, near London. Bayley’s loyalty to the D’Oyly family was due to his devotion to his late wife Elizabeth. When she died in 1832 he had a tall marble monument erected in the Norton Church cemetery at Stockton-on-Tees, upon which he had inscribed a poem that concludes with the words:

And I–But ah, can words my loss declare, Or paint th’ extreme of transport and despair? Oh, thou, beyond what verse or speech can tell My guide, my friend, my best beloved, farewell!1

The verse was probably written by his friend, Thomas Wemyss, who also wrote a poetical lament for Bayley entitled Reflections in Norton Churchyard, which Bayley circulated in 1834. Wemyss was a teacher and bible scholar who edited the journal The Dissenter.

In her last letter to her brother-in-law, Charlotte had disclosed that she and her family were about to embark on the long sea voyage back to India, thereby causing anxiety until confirmation came of a safe journey ended. It never did come. By March 1835, Bayley must have known that the D’Oylys had been shipwrecked near the Torres Strait and, by September 1835, that there was a possibility they might still be alive. By that time, they had already been missing for 13 months. He was devastated by the news. He had in his charge two boys whose parents and brothers had been among those lost and speculation about their fate was rife.

Armed with what little he knew, he travelled down to London and called upon Sir John Burrow at the Admiralty, to request a rescue ship. Advised to put his request in writing, he sent Burrow an emotional appeal, inviting ‘the attention of His Majesty’s Government (through you) to one of the most dreadful cases of shipwreck and murder or slavery or both that perhaps ever occurred’. He added, ‘ . . . as it is not unusual for the inhabitants of those Islands to preserve the females for purposes worse than death itself, I do implore the interference of His Majesty’s Government to send out a Frigate of War to rescue the poor surviving sufferers’.2

Burrow realised that Bayley’s appeal was based on speculation. He was sympathetic nonetheless, and passed it on to the Home Office, in charge of England’s colonies. A few days later the Home Secretary, Lord Glenelg, sent a dispatch to Governor Sir Richard Bourke at Sydney, instructing him ‘to adopt such measures as may appear to you most advisable for ascertaining the fate of these unfortunate persons, and for rescuing them from their present position’.3 Similar instructions were sent to Rear Admiral Capel, commander-in-chief on the British Navy’s East India station at Bombay. In those days, the Australian colonies were still under the East India station’s command. Since the information supplied was still scanty and without foundation, the usual practice in such cases was to instruct any ships passing through the area to inquire about any shipwreck survivors.

Bayley, meanwhile, continued to write letters to anyone he thought might have information or influence. Among the D’Oyly family’s relatives, imaginations were in full flight on both sides of the Indian Ocean, with particular concern reserved for Charlotte and her fancied existence as a sex slave. Bayley’s name was being mentioned in newspaper accounts, and he began to receive letters from anxious relatives and friends of the other missing passengers and crew.

One such letter was written by a Reverend at Dublin in Ireland. On Christmas Day 1835 he put aside church duties and festivities for a time to write to Bayley for information. ‘I had two friends on board the Charles Eaton – namely Captain Moore and Mr Armstrong,’ he wrote. ‘Paragraphs have appeared in the newspapers stating there was reason to believe the crew reached the Island of Timour [sic].’ He concluded that he entertained ‘very little hope’ that his two friends were still alive.4

In March 1836 the letter from the correspondent in Batavia, with the first brief statement about the four surviving shipwrecked sailors (Piggott having died at Batavia), arrived at Gledstanes. It was copied by their writers and distributed to interested persons. William Wardell – the coffee house proprietor and self-described bosom friend of Captain Moore and later the executor of his will – copied it again and passed it on to Bayley, who was both appalled and elated by its content. If nothing else, he thought, the sailors’ safe arrival at Batavia proved that survival in the seas north of Australia was possible.

A few days later an excited John Wardell sent Bayley a copy of the letter written by Captain Carr and just received by Gledstanes. In the letter, Carr claimed that there could be as many as nine shipwreck survivors at the Murray Islands. The news was ‘of such nature as to encourage the expectation of seeing or hearing of them again,’ wrote Wardell.5

Bayley immediately sent copies of both documents to Lord Glenelg at the Colonial Office, with his own distraught comment on the five sailors who had arrived at Batavia:

There had been a Mutiny on board, for why otherwise should they have left their Captain (Moore) clinging to the Main-chain, and my relatives Captain and Mrs. D’Oyly and their children standing near to the Captain, when the sea was so tremendous as to threaten immediate destruction to all remaining on board.6

Lord Glenelg sent another, more urgent, request to Sir Richard Bourke in Sydney, instructing him to ‘use every exertion in your power for the discovery of the sufferers and for relieving them from the deplorable position in which they are represented to be’.7

The Batavian deposition reached England in June 1836, and it, too, was distributed. John Wardell was greatly heartened by it, despite the grim nature of its content. He was confused about the difference between Timor Laut and the Torres Strait, and he wrote to Bayley, ‘I feel very confident about seeing our friends again; for it appears very evident it is not the custom of the natives to murder their prisoners.’8

Through all of this, no one supplied information to the chief mate’s father, the Rev. John Clare, and the same neglect applied to the families of the rest of the crew. With no news coming their way from Gledstanes, they had been depending on scraps of news picked up from shipping columns.

Clare was now an old and somewhat melancholy widower of 70. Although officially still the incumbent clergyman for the old Bushbury church in Staffordshire, he had abandoned the vicarage and moved to the Wolverhampton Deanery, where he had closer contact with his three spinster daughters and one other son, the Rev. George Clare, the first vicar of St. Georges at Wolverhampton.9 He knew that his son was assumed lost at sea, but the suspense of not knowing why so many rumours were circulating about survivors became intolerable. He contacted William Bayley, and thereafter the two men maintained a correspondence that sustained them both through their long wait for news. Clare found in Bayley a sympathetic friend who shared his family’s agony. He introduced himself to Bayley with the following letter:

My son was on board the CHARLES EATON, which, I am informed by the newspapers, has met with a disastrous fate; but the nature of that fate I cannot ascertain. In this dreadful state of hope and fear have I and my family been kept, for alas I cannot flatter myself that any rational gleam of hope can be indulged—if they are still alive, the state of slavery and misery in which they are left, is too appalling for the imagination to reflect upon. Perhaps the same wave that engulfed Captain D’Oyly has engulfed my son, and the same moment perhaps has closed the life and sufferings of both: pray communicate what you know, and do an act of kindness to an aged and unhappy father, who can too truly say, that since he heard of the melancholy fate of his son, he has never known a day of comfort, or a night of ease.10

Bayley sent Clare a warm and prompt reply, enclosing copies of Carr’s letter and the sailors’ Batavia deposition, the only fresh tidings he had at that time. Clare and his children eagerly received the information. Within days Clare was writing again to Bayley:

The depositions I have read with unwearied attention, and the result which burst upon my agonised heart is, if these are safe, why may not others be so? Every moment therefore, until the real fact is known, brings with it the alternative sensations of hope and fear, which the transition of a few months must make known to us.11

Clare was, by this time, one of Wolverhampton’s best-known citizens. An Oxford University masters graduate, he had been a lecturer in a protestant seminary for 10 years before becoming the vicar at the village of Bushbury, four miles from Wolverhampton. His teaching years had made him a confident and powerful speaker, capable of delivering stirring – if somewhat stern – sermons from his pulpit, for the benefit of his impoverished congregation of often unemployed coal-mine workers and farmers. Bushbury was part of England’s ‘black country’ of coalmines, but the workings around the village had already been largely exhausted.

For almost 40 years (1800–1839), Clare was also one of the region’s two senior magistrates. It was his true calling and career, but a position that he could only hold by also retaining his position as a clergyman. In order to be a magistrate in those days, one had to be either a member of the wealthy elite or aristocracy, or else you were a clergyman. Clare brought to the magistracy the disciplinary punishments of an old-fashioned religious zealot. The Sabbath day was sacrosanct and any indolent youth who failed to appreciate that fact was liable to end up in the town’s stocks for a few hours, where he had ample time to reflect upon his wicked ways.12 At the same time Clare tried to protect the interests of the poor, particularly against any unfair treatment at the hands of the wealthy mine owners who were the major employers.

Clare was a pioneer in industrial relations, trying to tread a cautious path between the mine owners who fuelled the local economy and bands of angry workers who felt their labour was being misused or abused. The industrial revolution was transforming Staffordshire and the magistrates were a part of it. When one angry man damaged some mining property, the crime was such that any other magistrate might have handed down the sentence of transportation to Australia. Clare, however, upon hearing that the mine owner had failed to pay the man his due wages, let him off lightly.

On another occasion he read the Riot Act at a meeting of angry voters in Wolverhampton in his capacity as the local magistrate, and several people were injured – one child very seriously – when troopers opened fire. It was a sad day that tainted the melancholic old man’s reputation and fuelled the argument that clergymen had no business being magistrates. Clare was called before parliament to explain his decision to read the Riot Act but no further action was taken.13

Growing up in the Clare household could not have been easy, with a father who was loving but also judgmentally strict and devout. Clare was now a widower, and his ongoing religious responsibilities at the villages of Bushbury and nearby Wednesfield, where he was also the resident curate, consumed the lives of two of his three daughters. Every Sunday they travelled with him to one or other of the villages, to help him to conduct the service and organise the choir. His life was their life, and all three girls never married. His other son, George, also took up the religious profession and became a vicar. Fred was the adventurous one. He escaped the oppressive life in the Bushbury vicarage and went to sea, becoming a midshipman in the East India Company’s maritime service. He wrote to his father, probably from Madras (now Chennai), when he transferred across to the Charles Eaton as the second mate, but when he got to London he did not visit the old man and did not tell him that he had now been promoted to first mate. He was, in his own way, still a devout Christian but he had his own life to lead.

His father loved all of his children, but as is so often the case, he loved his absent son in a special way. He was powerless to control his son’s destiny as he controlled the lives of his daughters, and could do no more now than pray for his son’s deliverance from death or, if not that, then pray for his soul.

Every second Sunday the bell at the old Bushbury church would toll out across the valleys to call the faithful to church, and announce that the Rev. Clare was in attendance. Now the toll, toll, tolling of the bell had an especially haunting sound. There stood the old stuccoed vicarage that Clare had organised to have built for his young family, vacant now except for caretakers, and overlaid with images of his son as a child, playing in the long grass of the churchyard. Those images belonged to a simpler time, when Clare had presided over a community surrounded by pastures and sectioned by cottage lanes, where the only sound on most days was the rumbling of cartwheels.

The old man’s heart was breaking, but he tried to put aside his pain by immersing himself in his increasingly onerous duties as a chief magistrate for Stafford. Clare subsequently learned that the man-of-war Tigris had left Bombay in March 1836, on a rescue mission to the Torres Strait. His friends had begun to add to the general pool of news and the old vicar was delighted to be able to make a contribution to the ongoing circulation of information.

A family friend in Sydney had written directly to Governor Bourke asking about any plans to rescue the shipwrecked passengers and crew. He was told that the colonial vessel Isabella would be sent to the Torres Strait to search for them and he immediately conveyed the news to the Clare family by the next ship to England. Another friend in London had been busy compiling news items collected from shipping columns, from which Clare learned that the ship Mercury was supposed to have proceeded with troops from Sydney to India via the Torres Strait, and intended to detour on the way through to look for the castaways. ‘It appears she did not get the troops,’ wrote a disappointed Clare, ‘and she did not sail through Torres Straits so that I must look to the Tigris alone.’14

William Wiseman, still commanding the ship Augustus Caesar, arrived in London in early September 1836 and was summoned on appeal from Bayley to appear before the Lord Mayor, Alderman Copeland, at Mansion House. Wiseman had been following the developments in the story with interest but in his deposition he could add nothing new to what was already known.

The ship Mangles arrived back at London in late September, more than 12 months after her visit to Mer. Captain Carr could hardly have been expecting a warm reception. James Drew, brother-in-law of Thomas Prockter Ching, a midshipman aboard the Charles Eaton, sought him out at the office of Mr Buckle, the then other part-owner (with Carr) of the Mangles,15 and his interview with the captain left him angry and dissatisfied. Carr, he complained, ‘gave a most meagre account of the circumstances’16. Nor was he happy with the responses of two of the ship’s mates, who ‘gave accounts which varied considerably’.17

In the end Drew managed to track down a sailor called Anderson who had been aboard the Mangles when Carr visited Mer, and he proved to be more forthcoming. He prepared a statement in which he outlined his own recollections of what had happened at Mer and received a half crown as payment from a grateful Drew. Anderson had corroborated what would later become Waki’s version of what had transpired. He would later admit to Carr, though, that he had been drunk when Drew interviewed him.18

Armed with Anderson’s testimony, the always impulsive and emotional Drew rushed down to the Lord Mayor and requested that his Lordship ‘give directions to the captain and crew [of the Mangles] to afford all information they possessed on the subject.’ He had reason, he said, ‘to suppose that more was known than had been stated’. Drew based his claim for the Lord Mayor’s assistance on the fact ‘that he had been on intimate terms of friendship with some of the unfortunate passengers, whose relatives and friends were in the most dreadful suspense as to their fate’ and also that he was ‘acquainted with Mr Bailey [sic]’.19 More importantly, his wife, Mary, was midshipman Tom Ching’s sister.

Drew was a partner in a wholesale and manufacturing pharmaceutical company called (at that time) Drew, Herward & Co., which had its premises in Great Trinity Lane, Bread street, close to Mansion House, the dockyards and Leadenhall Street. It was one of the largest wholesale druggists in London and in the 19th century it was a household name in England. His father-in-law, Thomas Ching Snr, was a druggist in Launceston, Cornwall, and Drew was also claiming intimacy with other members of the crew, including perhaps the other midshipman William Perry. He was well placed to take a prominent role on behalf of the Ching family and other anxious relatives and friends, and he plunged into that role with gusto. He had also contacted William Bayley in Stockton-on-Tees and the solicitor came to London to question Carr.

Alderman Copeland had previously shown deep interest in the mystery surrounding the Charles Eaton wreck and had personally interviewed William Wiseman, but on this occasion he refused to oblige. ‘Mr Buckle,’ he said, ‘was a person of first respectability and wholly incapable of concealing any information which it might be proper for the friends of the passengers and crew to receive.’20 Drew’s request, however, made it into the Times and brought the desired response from Buckle and Carr, with the latter not only volunteering to appear at Mansion House but also giving the London newspapers copies of his letter. Although it had already been published in China and Australia, it was the first time it had been released to the public in England. The Times published it on 4 November 1836 and like the Canton Register it added its own critical comment:

It appears extraordinary that on such an occasion as that described, more questions were not asked of the white man, and that, in fact, a narrative should have been written so destitute of minute particulars after so long a survey, and upon a subject of such deep and frightful interest . .

At three o’clock on the same day that the above press item appeared, Carr appeared at Mansion House. Many relatives and friends of the missing passengers and crew, including William Bayley, attended the meeting. Drew and William Wardell were there, as also was the Rev. Mr. J. W. Worthington, from the parish of All Hallows London Wall.21

Questions came from the assembly and voices were raised in anger. Bayley was a solicitor and he listened patiently while Carr gave his by now standard testimony then began his cross examination:

BAYLEY:—Did not the European mention his name, or the number who were on the island?

CARR:—Not to my knowledge. He did not say a word to me, neither did the natives. His skin was of the colour of mahogany, and he was naked, with the exception of a piece of skin round his waist. He tried as I heard from part of my crew, to get into the jolly-boat, but the savages drew him back.

BAYLEY:—Did you offer any ransom for him?

CARR:—No. I told my men to lower the boat and take him in. There was no time. I afterwards thought the best thing I could do was to go ashore myself, and I accordingly went into the cutter with six men and my second officer, and approached the shore. They brought an European boy, who appeared to be nearly three years old, towards us, and I offered them some axes for the child.

BAYLEY:—What sort of child was he?

CARR:—He had light curly hair, and was naked. They brought down the boy evidently to induce us to land. I saw a matted bamboo screen, behind which there appeared to be several savages passing and repassing.

BAYLEY:—Did you not fancy you saw some white feet amongst them?

CARR:—No; but I saw a boat building about 30 or 40 yards off. The child was about six yards from me at the time. It was decidedly an European-built boat,22 five planked, and capable of carrying from 20 to 25 persons to Java, at that time of the year. It was built with planks, but of what kind of wood I cannot tell.

BAYLEY:—Did you not see a lady’s petticoat hanging on the bushes?

CARR:—I saw with my glass what appeared to me to be a female garment on the bushes; but I have, when I have touched at the island on previous occasions, given female apparel to the natives. On my previous voyage, I sent one of their females ashore dressed in Mrs. Carr’s clothes.

Then the Rev. J. W. Worthington asked some pertinent questions:

WORTHINGTON:—How many guns do you carry?

CARR:—We have eight guns mounted on board.

WORTHINGTON:—Are not the savages greatly afraid of guns? Do they not throw themselves on their faces when a gun is fired?

CARR:—They do. They are excessively afraid of them.

WORTHINGTON:—My object in asking is to show that there was an adequate force to attempt to rescue those Europeans who might be detained in the island.

LORD MAYOR:—If it is meant to charge Captain Carr with having committed an offence in not making an attack upon the savages, I must stop the investigation. The captain might have hazarded the vessel and its large cargo if he had made any hostile attempt. His heavy responsibility was a serious consideration.

CARR:—If I had killed a single savage, the lives of all the Europeans on the island would in all probability have been sacrificed, and there is no knowing what lamentable consequences might have resulted.

DREW:—Did you offer no ransom for the Europeans when you heard that eight or ten of them were on the island?

CARR:—No; I offered ransom for the child.

At this point Drew began to express himself strongly on Carr’s failure to offer a ransom. He ‘seemed to be so much overpowered by his feelings as to excite general commiseration,’ wrote the Times reporter (probably John Curtis). ‘He was lamenting the fate of his wife’s brother, detained most probably by the natives of the island.’23 Drew, meanwhile, had been anxiously awaiting Anderson’s arrival, for the sailor had promised to attend. When it became clear he had reneged on his promise, the Lord Mayor read out Anderson’s statement. It contradicted Carr’s version of events on many points, claiming in particular that the cutter launched to rescue the man had not overtaken and hooked Duppa’s canoe. The Lord Mayor was dismissive, saying that no credit could be given to that part of Anderson’s statement that differed from those of other witnesses. Carr angrily denounced it, saying that he could not understand Anderson’s motive for ‘interlarding his statement with falsehood’24 as he was a good, sober and steady seaman.

The meeting was drawing to a close, but Bayley and Drew couldn’t resist a parting shot. In their opinion, ‘Captain Carr had not done what it was his duty to have done’.25 The parties then left Mansion House, with Bayley, Wardell, Drew and Worthington having achieved nothing except the satisfaction of giving Captain Carr a thorough dressing down.

A few days later, three sailors from the Mangles visited James Drew at Great Trinity Lane. The account they gave of Carr’s conduct appalled him. ‘They all agree in stating that Captain Carr could have bought them [the man and boy] with the greatest possible ease if he had been so inclined,’ wrote Drew in a letter to Bayley. ‘This conduct is altogether beyond conscience.’26

One of the sailors told Drew that the white man in the canoe had identified himself as Price, a native of Dublin, and that a lady and child had been saved from the wreck along with seven other seamen. Another sailor said the white man had told him another nine sailors had also been saved. Their evidence suggests that the survivor at Mer had a long but garbled and confusing conversation with them in which he tried to explain the circumstances surrounding his shipwreck, but on most points he had been misunderstood.

The Clare family, meanwhile, had received a clipping from Sydney’s Colonist newspaper in which an offer of 100 guineas had been made, specifically for the rescue of one person in particular:

ONE HUNDRED GUINEAS REWARD

Loss of the Charles Eaton.: To Masters of Vessels going through Torres’ Straits, from this Port, and from this date. –MR. WILLIAM MAYOR, an Officer on board the barque Charles Eaton, cast away in Torres’ Straits in 1834, being as yet unheard of; but believing, from the account of Captain Carr, of the Mangles, recently published in the Singapore papers, and copied from thence into The Sydney Herald of the 28th April, and THE COLONIST of the 5th May that some of the Officers, Crew, &c., are still on Murray’s Island, I hereby offer a Reward of One Hundred Guineas to any Commander of a Merchant Ship (not specially employed by Government for the purpose) who shall succeed in rescuing the said William Mayor from Murray’s Island, to be paid in London on receipt of certificate from the said W. Mayor; and I will remit approved endorsed Bills on London for the amount, to be lodged in the hands of the Agents of the Merchant here, who will endorse him.

HENRY BULL, Brother-in-Law of the said W. Mayor. Colonist Office, Sydney, May 12, 1836.

CAUTION. –The lives of all, if force is used to attempt their rescue, will assuredly be sacrificed-ransom by barter is the only chance. –H.B.27

Henry Bull had married William Mayor’s sister, Elizabeth, in 1832. They had sailed from England with their infant daughter in April 1834, arriving at Australia in September.28 One hundred guineas was a very generous reward from a man who was still recovering from two failed business attempts, including the loss of the schooner Friendship at Norfolk Island one year previously.29 Bull had jointly owned her with the vessel’s captain, John Harrison, and the family was left destitute when she sank in a gale. Since then he had become a part-proprietor and editor of one of the colony’s many newspapers, the above-mentioned Colonist, which may have improved his prospects. Also Elizabeth Bull stated that her brother had been about to come into considerable property when his ship was wrecked,30 so her husband must have been confident there would be no problem with the reward.

Throughout late April and early May of 1836, the Bulls had become increasingly frustrated by the lack of action from the New South Wales government in sending a rescue mission to the Torres Strait. As editor of the Colonist, Bull took full advantage of his position to express both his own and his wife’s dissatisfaction and to offer some suggestions for mounting a rescue mission (Colonist 28 April 1836):

There are at this moment no less than three vessels belonging to the same owners offered to Government for that particular service, viz. the brig Alice, the barque Francis Freeling, and the schooner Currency Lass—either of which, but more especially the latter, would answer the purpose; and His Excellency has not far to look for a commander, Captain C. N [sic] Lewis late of His Majesty’s Colonial Brig Governor Phillip, is well qualified for this important service.

The Governor Phillip had a damaged hull and would be in dry dock for many months, leaving Lewis temporarily without work. He got himself a nice little recommendation from the Colonist but he was probably the best choice to lead a rescue mission anyway.

When the Bulls got no response from Governor Sir Richard Bourke, Henry followed it up with another reprimand (Colonist 5 May 1836):

We have again to complain of the lethargy of the Government in not sending a vessel in search of the crew of this unfortunate barque. Another week has passed, and the humane instructions of the Home government appear to be no nearer execution than when the dispatches were first received. We have seen a letter from Captain King of Dunherd, since our last publication, but it appears that gentleman has merely been requested to lay down certain regulations for the guidance of whoever may go in command.

One week later, with still no official response for the colony’s government, the Bulls had placed their own advertisement in the 12 May edition of the Colonist, offering a reward to anyone prepared to undertake a rescue mission. A cutting was sent to Clare, possibly by the Bulls, who would have been aware of the chief mate’s background from letters sent by the second mate to his sister. It prompted another letter from Clare to Bayley: ‘My family and my daughters particularly wish me to contact you on this occasion and I shall be much obliged by your opinion and advice,’ wrote the reverend, for ‘some of the principal inhabitants of this town [Wolverhampton] came forward in the kindest manner to offer any sum for the same purpose’.

Clare ultimately declined the offer of the generous townspeople, believing any ransom offer was now too late ‘as the fate of the Charles Eaton is so universally known and so many efforts employed to seek them’.31 In an outpouring of emotion, the unhappy father concluded, ‘I cannot help thinking that now something decisive has taken place and that a few months will bring us the tidings of a joyful or heart-rending termination of all our hopes and fears.’32

Clare was correct in believing that they would soon receive definite news. Two days before Christmas 1836, a brief outline of recent events in the Torres Strait reached Gledstanes from Batavia via the homeward-bound Tigris. Their writers made many copies of it and letters were despatched by the next mail coaches. The relatives and friends of the missing passengers and crew spent the Christmas and New Year period overcome with shock and grief. Nothing and no one had prepared them for the news when it finally came. Once again it was the Rev. John Clare who summed up the prevailing despair when he sent a final letter to William Bayley in which he wrote: ‘their fate is so horrible that it precludes the possibility of comment.’33

In April 1839, Clare resigned as magistrate.34 He had no choice. The community he had served for so long considered him too old and too set in his ways. In 1838 he had sent a quarrelsome pauper girl to a penitentiary for a month and the sentence had provoked outrage. It was time to separate the Church from the law. Clare was planning to move out of the Wolverhampton Deanery, and had just spent more than 1000 pounds on a new home called Wood’s End at Wednesfield.35 On 11 July 1839, he was found hanged in the kitchen of the Deanery. A coroner’s inquest into his suicide received evidence that Clare’s health and spirits had suffered a severe shock two years before, owing to the fate that befell his son when he was shipwrecked in the Torres Strait. Mr. Clare never rallied after receiving that afflicting intelligence.36

It was a very sad end for a man who had devoted his life to Christianity and the administration of justice. In his own eyes suicide would have been deemed a heinous crime.

The other person with a close connection to the D’Oylys was Princess Mary the Duchess of Gloucester. Her husband had died in 1834 leaving his widow not unduly distressed. By October 1835 Princess Mary had already been informed that Charlotte had been shipwrecked and she wrote to Bayley, offering her assistance. It was accepted. In July 1836, Princess Mary went to Europe to visit her older sister Elizabeth, the Queen of Homberg, and stayed with her for five months. The holiday was a timely distraction, given that the Duchess was also enduring the painfully long wait for news from the Torres Strait.

By Christmas 1836, Princess Mary was back in England and she travelled to the Royal Pavilion at Brighton in the New Year to stay with the King and Queen. It would have been at this time that she first received the full details of the recent events in the Strait, either via the newspapers or perhaps in a letter from William Bayley.

Princess Victoria kept a daily diary and her entry for 10 January 1837 reads: ‘My aunt Gloucester was taken very ill last week with a violent nervous fever, and continues still very ill. She is quite delirious.’37 In those days the now antiquated term ‘nervous fever’ was occasionally used to describe a form of typhoid fever, possibly picked up in this instance while the princess was overseas. More commonly, it was used to describe the symptoms of what was subsequently called a nervous breakdown. Princess Mary was now in her late fifties. She had always been the carer in her family and had nursed her siblings through patches of both short and prolonged ill health. She had suffered a similar breakdown after the death of her sister, Princess Amelia. Now her brother, King William IV, was there for her, as she worked her way through her severe illness and her grief at the news. She had known Charlotte D’Oyly since she was an infant and had witnessed and shared her growth to womanhood. For both women the friendship had been long and genuine.

..

Notes to Chapter 11

- William D’Oyly Bayley, A Biographical, Historical, Genealogical, and Heraldic Account of the House of D’Oyly, London: J. B. Nichols and Son, 1845, p. 153.

- HRA, Series 1, vol. XVIII, p. 168–69 for whole of letter. Robert D’Oyly, lawyer and brother of Tom D’Oyly, made a similar appeal but it was not forwarded to New South Wales.

- HRA, Series 1, vol. XVIII, p. 168.

- William Bayley file. Letter to Bayley, sender’s name obscured by thought to be the Rev. Worthington, 25 Dec. 1835, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, A1074,

- William Bayley file, J. Wardell to William Bayley, March 1836. Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, A1074,

- HRA, Series 1, vol. XVIII, pp. 372.

- Ibid.

- William Bayley file, Letter from J. Wardell to William Bayley, 22 June 1836, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, A1074.

- For biographical information about the Rev. John Clare, see The Annual register or a view of the history and politics of the year 1839, vol. 81, London, J.G.F. & J. Rivington, 1840, p. 136; The Gentlemen’s magazine, vol. 166, p. 209; Roger Swift, ‘The English Urban Magistracy and the Administration of Justice during the Early Nineteenth Century: Wolverhampton 1815–1860’, Midland History, 17, 1992, pp. 75–92.

- Thomas Wemyss, Narrative of the Melancholy Shipwreck of the Ship Charles Eaton . . . , Stockton-on-Tees: W. Robinson, 1837; 2nd ed. Stockton-on-Tees: J. Sharp, 1884, p. 16.

- Wemyss 1884, pp. 16–17.

- Midland History, vols 13–17, p. 79.

- David J. Cox, ‘ “The wolves let loose at Wolverhampton”: a study of the South Staffordshire Election “riots”, May 1835’, Law, Crime and History, 2011, p. 2.

- William Bayley file. Letter from Rev. John Clare to William Bayley, 14 Oct. 1836, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, A1074.

- By 1835, Captain Carr was also being described as the owner of the Mangles, so presumably they were joint owners before Carr became sole owner.

- The Times, 1 Nov. 1836.

- Ibid.

- See The Times, 5 Nov. 1836 for Anderson’s complete statement.

- The Times, 1 Nov. 1836.

- Ibid.

- The Times, 5 Nov. 1836 for details of the Carr interview. Worthington’s connection to the Charles Eaton was given as being a close friend of William Bayley. He was teaching at the All Hallows at London Wall church school in the City of London at a time when the parish was sending pauper and orphan children to the Children’s Friend Society for shipment to the colonies. Even that connection, however, does not quite fit. Perhaps a relative of Armstrong, Captain Moore, or one of the crew was a parishioner in his church and he had been communicating with Bayley on their behalf.

- There is no supporting evidence that this boat ever existed. Carr saw the wrecked stern of an old boat previously washed up on the island and revered by the natives as a kind of religious relic.

- The Times, 5 Nov. 1836.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- William Bayley file. Letter from James Drew to William Bayley, Nov. 1836, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, A1074.

- Henry Bull married William Mayor’s sister, Elizabeth, 10 October 1832, at St Andrew’s Holborn, Middlesex, England. Source: IGI. They arrived in Sydney with one infant child in late 1834. After two failed business attempts, Henry became the editor and joint proprietor of the Colonist in October 1835.

- Bull’s own brief autobiography, published in the Colonist 1 October 1835, states that he first met the Rev. Dr. Dunmore Lang in January 1834, when the Bulls were about to sail for Upper Canada. Lang was Australia’s first Presbyterian minister and the proprietor of a religious newspaper in Sydney called the Colonist. He sang the praises of the NSW colony and persuaded the Bulls to change their destination to Sydney. Shipping passenger lists indicate that they came out aboard the Rossendale, which docked at Hobart Town 10 Sept. 1834 and a few weeks later in Sydney. Bull, acting as his own agent, apparently stocked some of the hold with his own adventure cargo, hoping to sell it for a profit at Hobart and Sydney, but the venture failed. Lang had advised Bull not to do that, but he had gone ahead with the idea anyway.

- The Sydney Monitor, 22 Aug. 1835, p. 4, gives Bull’s own lengthy and graphic account of the Friendship shipwreck and it makes compelling reading.

- William Bayley file, letter from Rev. John Clare to William Bayley, Nov. 1836, Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, A1074.

- William Bayley file, Clare to Bayley, Nov. 1836, A1074.

- Ibid.

- William Bayley file, Clare to Bayley, undated but probably January 1837, A1074. For a long time it was assumed that the Rev. John Clare was the clergyman described by George Borrow in his book The Romany Rye (published in 1848 but describing events in 1825). While there is no concrete evidence to support this, Borrow’s description is remarkable for the way in which it does actually appear to describe the widowed Clare and his daughters, or at least people very like them. Clare was no evangelist – or at least not officially – but years of writing sermons had made him a passionate and powerful wordsmith. Bayley was so touched by his letters that he quoted them extensively in his book and they have since been acquired by the State Library of New South Wales as part of the Bayley collection. Today it is still possible to be moved by the old vicar’s tears and fears. He was clearly respected by many of the townsfolk of Wolverhampton and the villagers at Bushbury and Westerfield (he was the vicar for both villages), and the son was like the father in that he enjoyed the respect of his crew.

- Records of the Staffordshire County Quarter Sessions, April 1839, item 44.

- Law Journal Reports,vol. 24, part 2, 1855, p. 110. Lengthy court case about the title to the house and land purchased by Clare. Clare’s unfounded belief that he would lose his money may have contributed to his suicide.

- Annual Register or a View of the History and Politics of the Year 1839, vol. 81, London, J. G. F. & J. Rivington, 1840, p. 136. Also see: The Gentlemen’s magazine, vol. 166, p. 209. It was the second sudden death in the Clare quarters at the Wolverhampton Deanery. In April 1838, the Rev. John Clare’s orphaned niece, Sarah Lee Clare, died there at the age of 26 and the circumstances of her demise were not included in her short death notice. It’s known, however, that the Clare womenfolk were devastated by Chief Mate Fred Clare’s death.

- Flora Fraser, Princesses: The six daughters of George III, New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 2005, p. 362.

.

.Chapter 12: colonial schooner Isabella to the rescue

In a seaport obsessed with its harbour, custom dictated that one of the best views of it would be reserved for the incumbent of Government House. For Governor Sir Richard Bourke, the vista of busy Sydney Cove in late May 1836 included the activity around the Governor’s Wharf and the colonial schooner Isabella. The prison service employed the vessel primarily to carry stores, troops and convicts to the penal colonies on Norfolk Island and at Moreton Bay. For her next voyage, however, she was taking on extra stores for a mercy mission to the Torres Strait.

When Governor Bourke had received the dispatch from Lord Glenelg raising the possibility that as many as nine shipwreck survivors were being held captive in the Torres Strait, and instructing him to ‘adopt such measures as may appear to you most advisable’,1 he had been less than enthusiastic. In his opinion, sending one of His Majesty’s men-of-war from Bombay or the South Seas to investigate the claim was a more appropriate response. He had to obey the order from the Home Office, however, despite the fact that it would engage the Isabella for several months. The prison service would have to charter another vessel in her absence, placing a strain on its tight budget. Bourke was humane and reasonable but the rumours about survivors appeared to be groundless. The publication of Captain Carr’s letter in the 28 April 1836 editions of Sydney newspapers,2 however, put the question of survivors beyond doubt. Thereafter he acted with commendable speed, although he did have to wait until the schooner had returned from her latest trip to Norfolk Island.

The Isabella was registered for 126 tons and measured in feet 76 x 19 x 11 (approx. 23 x 5.8 x 3.4 in metres). Commander for the Torres Strait mission would be Captain Charles Morgan Lewis R.N., who volunteered for the assignment. He was a navy skipper employed by the colony on another colonial vessel. Born in Norfolk, England, in 1804,3 he was an ambitious 31-year-old who had previously been a master mariner in the navy of the King of Siam (Thailand).4

Interest in the survivors was widespread and the public expected action. Sailors lined up for a voyage bound to be more interesting than the monotonous treks back and forth to the two penal settlements. The schooner’s full crew compliment was usually 18, but for the rescue mission it was increased to 31.5 Despite the obvious activity surrounding the little schooner, no official statement was issued. Nevertheless, newspaper reporters picked up her destination, possibly via the customs and shipping documents they habitually perused. She was ‘supposed to be the recovery of the survivors of the wreck of the Charles Eaton,’ guessed the Australian in its 17 May edition.

The news excited the attention of a retired seaman, William Barnes, who was now a resident of New South Wales but who had once been the master of a vessel called the Stedcombe. Barnes had his own story to tell. In 1825 the Stedcombe and the Lady Nelson had left a short-lived British settlement at Melville Island, on the northern coast of Australia, on a mission to trade for buffaloes from one of the islands in the Timor sea. Both vessels had been cut off by pirates and everyone assumed that all aboard them had been murdered.6

The Batavia deposition from the five sailors, recently published in Sydney papers, gave an account of two other boys cast away on Timor Laut many years previously. Barnes concluded that they were, in all likelihood, the two ship’s boys from the Stedcombe, names John Edwards and Joseph Forbes. He was horrified to think that they had been in bondage and slavery for so long and he wrote to Governor Sir Richard Bourke with a special plea. The Isabella would be passing near Timor Laut on her return voyage. Could the vessel stop at Timor Laut to make enquiries about the other two boys?7

Captain Lewis of the Isabella received instructions from the Colonial Secretary to call upon Barnes and he did so. Barnes was now a portly stock and land auctioneer, residing in Paramatta but a frequent visitor to Sydney. He gave Lewis every scrap of information that he had collected from his voyages around the Timor seas, including his time aboard the Stedcombe. He also lent Lewis his ship’s journal. In return, he received from Lewis an assurance that on the homeward journey he would make a thorough search for the two English boys presumed to be in slavery at Timor Laut.8 Lewis said his farewells to the talkative former adventurer and sea captain with what appears now to be no intention of keeping his promise.

By 24 May most of the crew were aboard and helping with the fit-out. Included among them was William Edward Brockett, who kept a journal that he later published as a booklet. Brockett was from Newcastle in England, and the rescue mission to the Torres Strait would be the highlight of his Australian experience. He was in his twentieth year and was enjoying what we would probably call today his ‘gap year’, while he decided what he wanted to do next. An adventurous seafaring life was appealing but was it right for him? He seems to have been testing his choice by working his way around the world as an ordinary seaman.

Brockett was the son of John Trotter Brockett, a well-known attorney in Newcastle, England and a prominent personality in that city. His father had many other interests besides law, including writing and illustrating books on coins and medals. His best-known book, however, was a useful glossary on the numerous words unique to northern England, for the benefit of southerners who struggled to understand the local idioms. But John Trotter Brockett was also an addicted collector of books, artworks, stamps, coins and antiques. His son had grown up in a house that was described in the following terms by an old friend, the bibliomaniac, Dr. Dibdin:

More than once or twice was the hospitable table of my friend, John Trotter Brockett, Esq., spread to receive me. He lives comparatively in a nut-shell—but what a kernel! Pictures, books, curiosities, medals, coins—of precious value—bespeak his discriminating eye of his liberal heart. You may revel here from sunrise to sunset, and fancy the domains interminable. Do not suppose that a stated room or rooms are only appropriated to his bokes; they are ‘up-stairs, down-stairs, and in my lady’s chamber.’ They spread all over the house—tendrils of pliant curve and perennial verdure.9

William Brockett had spent his childhood in a household where almost constant literary output was a part of everyday life, but living in a small dwelling with a compulsive collector and hoarder couldn’t have been easy.

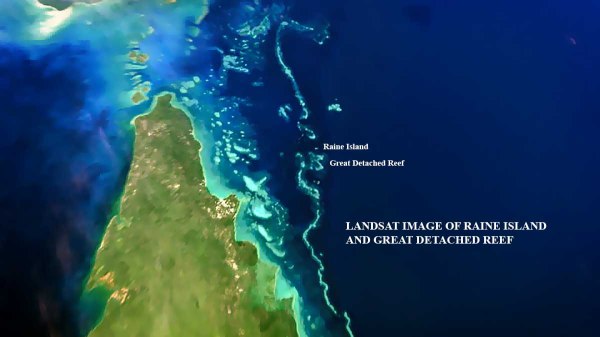

On 30 May, Lewis received his final instructions from Governor Bourke, with sailing directions supplied by Captain Phillip Parker King, RN. He was to proceed directly to the Murray Islands via the outer passage, passing through the reefs at either the Investigator or Cumberland entrances.10 It must have been one of the few occasions when King recommended the outer passage, but Lewis would be following the chart laid down by Matthew Flinders. Flinders had called at Mer – something that King had never done. If there were white people on the Murray Islands, Lewis and his men had to rescue them without resorting to violence, unless it was necessary for the defence of life.

The Isabella sailed from Port Jackson on 3 June, fitted out with cannons and plenty of ammunition, plus a good supply of iron axes and trinkets. Lewis had also accepted a box of goods from Elizabeth Bull specifically for her brother, second mate William Mayor, in case he was alive. Everyone believed that in addition to the lad and child seen by Carr, there were nine or more other survivors at Mer.

Four days later the Indian navy’s brig H. C. Tigris, dispatched from Bombay under Commander Igglesden, left Hobart Town for Sydney en route to the Torres Strait. Also on board was 2nd Lieut. George Borlase Kempthorne. Caught in a gale on 11 June almost within sight of Sydney’s lighthouse, she sailed into the colony on 12 June with some damage to hammocks and top deck. It was a sunny Sunday and a large crowd gathered at vantage points along the government domain and at Garden Island to witness the arrival of what was, for most of them, their first sighting of an Indian man-of-war. The ‘novel attire’ of the Indian lascars (sailors) and sepoys (soldiers) may have ‘excited their curiosity’.11

Most of the spectators knew why the Tigris was there. The plight of the shipwrecked sailors had aroused their sympathy and they had been demanding action. The smaller government schooner had already been dispatched for that purpose, but the 255-ton Tigris, with 10 guns and a larger ship’s company, was a much more impressive and reassuring sight.

The H. C. brig-of-war Tigris had been launched in 1829 for the Company’s service and was not registered with Lloyd’s Register of Shipping. At the time of her visit to Australia, the Indian Station (formerly the Bombay Marine until 1830) was in a depressed state and there was even talk of disbandment. It no longer had a practical purpose and morale among the navy’s many talented captains, commanders and officers was low.12 Even the smallest of pirate ships could easily outrun the Tigris.13 In size, the two-masted brig-of-war was similar to the average three-masted mercantile barque, but her rigging was more complex and needed a bigger crew. Brigs-of-war could turn on a sixpence but they often lacked the necessary speed to chase down and engage the enemy. The Tigris, however, was considered both fine looking and fast by the standards of her class. The Company’s warships were divided into six classes, depending on their size and the number of guns. The Tigris was on the bottom rung as a Class Six, with a lower-ranked Commander in charge rather than a more senior Captain. Assigning her to a rescue mission for shipwrecked survivors was in keeping with her current standing in the Indian navy as a reliable work horse.

Sending the brig-of-war to the Torres Strait seems like a crazy decision, but at least it kept the crew busy for a time. The Tigris looked exotic with all those smart Indian sepoys and artillery gunners in their uniforms, but scurvy had broken out by the time the brig reached Hobart Town, simply for the want of enough fresh or appropriate produce in the ships’ stores. Kempthorne was understandably cross that keeping costs to a minimum had endangered the lives of all aboard the ship. ‘The “penny wise and pound foolish” system was in this instance very apparent,’ he later complained.14 The rebuke might have been levelled against Commander Igglesden, who had originally intended to call at the friendly Cocos/Keeling Islands, to procure fresh water and supplies. The Cocos/Keeling Islands are a mere dot in the middle of the Indian Ocean but they were the ideal stopover for any vessel sailing between India or Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and Australia. The Tigris missed the landmark because of severely adverse weather and Igglesden decided to push ahead rather than waste time turning back. The time saved in not visiting the islands was negated by the desperate need to stop over at Hobart Town instead, with his pursers running out of drinking water and food.

Fortunately the Lieutenant-Governor of Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania), Colonel Sir George Arthur, rendered them every assistance and, said Kempthorne, ‘did all in his power to expedite the departure of the Tigris on its important mission.’15 The immediate supply of water and fresh food quelled the dreadful disease. There would have been many free settlers in Hobart Town who met the D’Oyly family during the almost nine months they lived in New Norfolk. They had arrived in the colony with impeccable references and Colonel Arthur himself may have organised the swift supply of their convict servants.

Governor Bourke had been unaware of the action taken by the Bombay station and he would have been unimpressed by the overkill in sending two rescue ships to the same tiny island. Fortunately, repairs to the Tigris stretched out to 28 days and the man-of-war did not depart for the Murray Islands until 10 July, placing the decision to send the Isabella beyond reproof. The Tigris had left Bombay with a man on board who was found to be suffering from smallpox and the brig had been quarantined at Ceylon for a time, contributing to her delayed arrival at Sydney. Bourke, however, was kind. He gave Commander Igglesden a duplicate of the instructions given to Captain Lewis, so that he could meet up with the Isabella schooner in the strait.

Brockett, meanwhile, was maintaining his journal of the Isabella’s voyage. The captain, he wrote, had ordered him to scratch some empty glass bottles with the following inscription: ‘C. M. Lewis, Commander of His Majesty’s Schooner, Isabella, is despatched by Government to obtain the people who were lost in the Charles Eaton; June, 1836. (From Sydney). Secret.16

Governor Bourke had ordered Lewis to prepare and distribute a number of these bottles around the islands on the off chance that any shipwreck survivors who read the message would find an opportunity to escape. Lewis would have known by that time that Brockett was up to the task and his scratched words would be legible.

Sunday 19 June began as a thick and hazy day. At nine o’clock Mer was seen by the lookout up the masthead and at 11 o’clock, having successfully negotiated Cumberland’s passage through the Barrier Reef, the schooner anchored on the northern side of Mer. A group of islanders gathered on the beach, extending their arms in signs of peace and indicating they wanted to trade. Among them the sailors and officers could plainly see a naked white man. It was Waki. He had seen the schooner coming and had gone straight down to the beach, where some of his friends were already launching their canoes.

Lewis, in some doubt as to whether the islanders could be trusted but wanting to encourage them to visit, ordered all the loaded cannons to be pulled back and sent half the crew below. His men were armed, however, and ready to repel an attack if necessary.17 As the canoes were being pushed off from the beach, Waki tried to get into one of them, but his island father stopped him. Duppa was convinced that the last time a ship [the Mangles] had called at Mer, the crew had tried to take Waki away and kill him. Waki pleaded with Duppa for some time but the old man refused to let him go out to the ship. He told Waki to go and hide among the trees on the hill instead.

Four canoes soon reached the schooner and their occupants began making signs of friendship, calling out ‘poud, poud’ (peace, peace). Their platforms were laid out with trade items which they held up in the air, calling ‘torre, torre’ for iron axes and knives in exchange. The schooner’s crew now began to make signs, pointing at their own faces then at the island, by which they managed to ask if there were any white people there. The islanders gestured to indicate there were two. With more signs, Lewis pretended not to understand what the canoeists wanted, hoping they would fetch the white person as an interpreter. The sailors held iron axes aloft to excite the visitors and when there was no progress with the trading, sure enough, the islanders decided to fetch Waki, and returned to the beach. Duppa, however, still refused to let Waki go. ‘I don’t want to leave you,’ Waki reassured him, explaining that he only wanted axes and other articles like everybody else.18 Finally he was allowed to get into Duppa’s canoe and he sat down on the platform amidships while the men rowed him out to the vessel. This time he was determined that there would be no misunderstanding, so he asked everyone to keep quiet until he had spoken to the people on the ship. Lewis had issued similar instructions to his crew and there was total silence as the canoe reached the Isabella. Brockett wrote in his journal, ‘the unfortunate boy exhibited the mingled emotions of fear and delight.’ Everyone, wrote Brockett, ‘appearing to listen with the greatest attention.’19

‘What is your name?’ asked Lewis.

‘John Ireland,’ the boy replied.

‘How many are upon the island?’

‘Only a child about four or five years old.’ The rest of the white people, said Ireland, had either drowned or been murdered.20

As he later explained it:

My agitation was so great, that I could scarcely answer the questions which were put to me; and it was some time before I recovered my self-possession. Captain Lewis took me down into the cabin, and gave me a shirt, a pair of trousers, and a straw hat. He ordered some bread and cheese and beer for me; but the thoughts of again revisiting my home and friends prevented me from eating much of it.21

Now that one boy had been rescued, brisk trade was permitted, with the scratched message bottles being handed out as presents in the hope they would be found by other survivors. In the cuddy, Captain Lewis waited until he could see that the boy had recovered his senses and was ready to tell his story.

.

Notes to Chapter 12

- HRA, Series I, vol. XVIII, Lord Glenelg to Governor Sir Richard Bourke, p. 158.

- This is the letter dated 4 October 1835 and written by Carr while en route to Canton.

- England and Wales Census, 1851.

- Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser , 25 Dec. 1832.

- HRA, Series I, vol. XVIII, Sir Richard Bourke to Lord Glenelg, 9 June 1836, pp. 432–34.

- Charlotte Barton (A Lady Long Resident in New South Wales), A Mother’s Offering to Her Children. Sydney: printed at the Gazette Office, 1840, pp. 100–136; J. Lort Stokes, Discoveries in Australia; with an Account of the Coast and Rivers Explored and Surveyed during the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle, in the years 1837‑38‑39‑40‑41‑42‑43, by Command of the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty. Also a Narrative of Captain Owen Stanley’s Visits to the Islands in the Arafura Sea, Australiana Facsimile Editions no. 33. Adelaide: Library Board of S.A., 1969, pp. 440–78.

- Sydney Monitor 30 July 1839.

- Ibid.

- John Trotter Brockett and Charles Edward Brockett (ed.), Glossary of North Country Words in Use, with Their Etymology, Affinity to Other Languages, and Occasional Notices of Local Customs and Popular Superstitions, 2 vols, 3rd edn, Newcastle-on-Tyne: Emerson Charnley, London: Simpkin, Marshall & Co., 1846, vol. 1, p. xxi.

- Named after the first vessels to use them, including Matthew Flinders’ Investigator. Both are close to the Murray Islands.

- Commander G. B. Kempthorne, I. N., ‘A Narrative of a Voyage in search of the Crew of the Ship Charles Eaton performed in the year 1836’, Transactions of the Bombay Geographical Society, vol. 8, 1847-1849, pp. 210–36.

- Jean Sutton, Lords of the East: The East India Company and its ships (1600–1874), Chap. 11, pp. 127–39.

- Sutton pp. 127–39.

- Kempthorne, p. 217.

- Ibid.

- Wiliam Edward Brockett, Narrative of a Voyage from Sydney to Torres’ Straits : in Search of the Survivors of the Charles Eaton, in His Majesty’s colonial schooner Isabella, C.M. Lewis, commander, Sydney: printer Henry Bull, 1836, pp. 10–11.

- Captain C. M. Lewis, ‘Voyage of the Colonial Schooner Isabella . . . ’, Nautical Magazine, vol. VI, 1837, pp. 654.

- John Ireland, The Shipwrecked Orphans, New Haven: S. Babcock, 2nd edn, 1845, p. 56.

- Brockett p. 13.

- Australian, 20 Oct. 1836.

- Ireland p. 56.

… …

…

…

.Chapter 13: one night at Boydang Cay

The tradition about a captain being the last to leave his ship is an old one. The crew left behind on the wreck after Moore’s raft disappeared, felt so abandoned, for a time they gave into despair. With their popular chief mate now in command, however, they soon set to work on another raft, made from the remaining spars. The second raft, like the first one, took a few days to build. It was a solid piece of work, with its own mast and calico sail. With only a few damaged biscuits and a little water, the unhappy sailors launched it, trying to steer with the wind. The simple craft sank under their weight, leaving them at the mercy of the current.1

The heavily laden raft made very slow progress. It drifted for many miles before the sailors encountered another reef with enough shelter on its lee side to offer a safe haven for the night.2 After that they saw no more reefs and had entered the inner passage. For two more days they drifted, with all their biscuits and water soon gone.

On the fourth day, they passed an island and could see more low isles ahead. Before they could reach them a canoe came out to meet them, paddled by 10 or a dozen natives who had been fishing on a nearby reef.3 As they approached, the men in the canoe stood up and extended their arms in a gesture that showed they were unarmed and friendly. ‘On their reaching the raft’, Ireland later explained, ‘several of them got upon it, and were gently put back by Mr Clare; he at the same time saying that he thought from their manners that they were not to be trusted. They were very stout men, and quite naked.’4 One man, however, stayed behind on the raft, attracted by a piece of white cloth at the top of the mast. He tried to climb up and get it but the mast snapped, throwing him into the sea. At any other time it might have been amusing but not now, for the raft’s single mast and sail were gone.

Even so, the mood remained friendly. The sailors gave the natives a mirror and a piece of red cloth. The gifts pleased them and they invited the white men to transfer across to their canoe. For a time the sailors hesitated, until midshipmen Tom Ching took the lead. ‘I’m going with them,’ he said, ‘because it might mean getting back to England sooner. At any rate,’ he added as he scrambled into the canoe, ‘I could not be worse off.’ Then everyone followed him and left the raft, at which time the canoeists searched it for iron tools but could find nothing but a few old keg hoops, probably from the empty water cask. These they placed in their canoe and let the raft drift away.

‘It was about four in the afternoon when we left the raft,’ said Ireland, ‘and after passing three islands on our right, and one on our left, we landed on an island which I afterwards found the natives called Boydan [Boydang]. We could plainly see the main land, about fourteen or fifteen miles distant.’ As they approached the beach, Ireland could see a second canoe drawn up on the sand but no huts or shelters of any kind. The ominous signs were already there that this tiny island was fine for turtle and lagoon fishing but hostile to habitation.5

As soon as they had landed, the sailors pointed to their mouths and made signs to show they were hungry and thirsty. With their rescuers walking beside them and still giving every sign of being friendly, they set off around the island, hoping to find food and water. Their journey was short but they were so exhausted by fatigue and hunger, by the time they returned to their starting point they could barely crawl. They had found nothing to eat and no water supply, and could do no more than throw themselves down on the sand in despair. Sensing their weakness, the mood among their rescuers changed. They laughed and seemed to take pleasure in the sailors’ anguish. No longer their hosts, they had become their captors.

Observing this change in their attitude, the chief mate warned his men to prepare for the worst. ‘He read some prayers from a book which he had brought from the wreck,’ said Ireland, ‘and we all most heartily joined with him in supplication. We felt that probably it would be our last and only opportunity while here on earth.’ The men prayed together in a group for a long time but eventually they crawled under some bushes, too tired to resist sleep any longer.

‘Although it will readily be imagined we were little in heart disposed to slumber, yet such was the state to which we were reduced, that most of us fell almost immediately into a sound sleep,’ Ireland later explained. They were encouraged by the islanders who sensed their weak attempts to resist sleep and sought to induce it by putting their own heads down on one shoulder and closing their eyes so that they, too, appeared to be dozing off.

Sleep came slowly to the young ship’s boy. The sun was setting but it was still possible to see a few islanders moving around on the beach. One of them went down to his canoe and came away from it walking in a strange manner. He was advancing cautiously with a club in his hand but hidden, as he thought, behind his back. Later he dropped it stealthily upon the beach. ‘I told this to the seaman, Carr, who was lying next to me,’ said Ireland, ‘but he, being very sleepy, seemed to make no notice of it, and soon after was in a deep sleep.’

One by one the sailors drifted into slumber and as they did so, the ship’s boy observed with dread that the islanders were creeping forward and placing themselves so that there was one of them between each sleeping form. Ireland was so weary, however, that he, too, eventually fell asleep. As he would later explain, ‘It was utterly out of our power to resist; as we had not so much as a staff or stick to defend ourselves with; and our exhaustion was too great to allow us to quit the place’.6

After he had been asleep for about an hour, Ireland woke up suddenly to the sounds of terrible shouting. He jumped up instantly and saw that the islanders were killing his companions. The first to die was the little midshipman, Tom Ching, followed by his young friend, William Perry. The next victim was William Mayor, the second mate. ‘The confusion now became terrible’, said Ireland, ‘and my agitation at beholding the horrid scene was so great that I do not distinctly remember what passed after this.’

Some of the sailors had their brains smashed and skulls cracked, while others were stabbed with spears and knives. As they fell wounded, their attackers rushed forward and, seizing them by their hair, slashed or hacked off their heads with razor-sharp knives.

The last person Ireland saw murdered was the chief mate, who put up a tremendous fight. He cleared a path for himself through a group of advancing attackers and raced down to the shore, with several islanders in pursuit. Reaching a canoe, he pushed it off into the sea. His pursuers plunged into the water after him and soon overtook him. Grabbing up the paddles one by one, Clare lashed out at them and was successful for a time, but in the end there were too many attackers and they overpowered him. Abandoning the canoe, he jumped back into the water and again dashed into the midst of his attackers. Breaking through them, he raced through the shallows until he regained the shore, and made off into the bushes. He was increasing the gap between himself and his pursuers when a party lying in ambush jumped up and felled him to the ground, where they immediately killed him and cut off his head.7

When Ireland, who had been staring in shock at Clare’s horrendous death, finally looked around again he could see that he and the other ship’s boy were now the only two people from the raft left alive. A large man, whose name, he would later learn, was Bis-kea, came towards him with a carving knife in his hand, which Ireland the young assistant steward now recognised as having belonged to the cabin galley until placed with the stores on the first raft. Bis-kea seized him and held the knife in such a way that the lad believed his throat was about to be cut. ‘I grasped the blade of the knife in my right hand and held it fast,’ he explained. ‘I struggled hard for my life.’ Finally, Bis-kea threw Ireland down on the ground and, placing a knee upon his breast, tried to wrench the knife away. Still the boy held tight to it, until it cut one of his fingers to the bone. While struggling with Bis-kea, he saw that Sexton was in the grip of a man whose name, he would later learn, was Maroose. In desperation, Sexton bit Maroose and took a piece out of his arm. ‘After that,’ said Ireland, ‘I knew nothing of him, until I found that his life was spared’.

For a brief moment, the boy got the better of Bis-kea and he let go his hold on the knife and ran into the sea. He stayed semi-submerged for a long time with no one in pursuit. He was determined, he said, ‘to swim out and be drowned rather than be killed and eaten.’ In the end, however, fright and weariness got the better of him and he gave up and return to the shore, it being, he said, ‘the only chance for my life’.

Back on the beach, the islanders were going about their gruesome business. They had built a large fire and appeared to have forgotten about the boy. Even so, as he crept back through the shallows in the enveloping darkness Ireland expected death at any minute.

There are two versions of what happened next. In the one recounted by Captain Phillip Parker King, Bis-kea was waiting for him on the shore and came towards him in a furious manner, shooting an arrow at him which struck him in his right breast. ‘On a sudden, however, he, very much to my surprise, became quite calm, and led, or rather dragged me to a little distance, and offered me some fish,’ said Ireland.8

Another version was given to a Sydney reporter, ‘When I returned to the beach the same man again got hold of me, but instead of further molesting me, he gave me some food and water’.9 Bis-kea, said Ireland on another occasion, ‘saved me from violence from the hands of the others.’10

Ireland was left sitting on the beach. He was very hungry but too afraid to eat any fish for fear it was poisoned. Not far off, his captors were dancing around a large fire they had lit upon the sand, before which they had placed, in a row, the heads of all his dead countrymen, still recognisable despite their bloody wounds and sightless eyes. The headless bodies were naked now and carelessly left on the beach. ‘I should think the tide soon washed them away,’ Ireland explained, ‘for I never saw them afterwards.’

The heat from the fire partially cooked the heads, at which time the men began to cut off pieces of flesh from the cheeks and other parts of their faces, plucking out the eyes and eating them with triumphant shouts. ‘This, I afterwards learned, it was the custom of these islanders to do with their prisoners,’ the ship’s boy explained, ‘they think that it will give them courage, and excite them to revenge themselves upon the enemy.’ It was ritual cannibalism in other words. The central islanders, like the rest of the Torres Strait Islanders, had no taste for human flesh. There was an abundance of fish and turtle meat.

In what would become the final version of his story, Ireland stated that Sexton also survived for a time. The two terrified boys sat close to the fire, he said, where the mutilated heads were still on display. Some of their captors, ‘sat like tailors, dividing the cloth and other articles which they had taken from the bodies of the persons killed.’ Already, however, some of the men were showing signs of wanting to be kind. Two of them went down to a canoe, took down the woven-grass sail, and covered the boys to keep them warm again the cold night. To Ireland’s annoyance they ignored his badly cut finger. What followed was a very long night indeed. As Ireland said:

It is impossible for me to describe our feelings during this dreadful night. We fully expected, every moment, to share the fate of those whom we had so lately seen cruelly murdered. We prayed together for some time, and after each promising to call on the other’s relations, should either ever escape, we took leave of each other, giving ourselves up for lost.

At length the morning came; and the Indians, after having collected all the heads, took us with them in their canoe to another island, which they called Pullan, where the women lived.11

Notes to Chapter 13

- It’s possible that when the crew were up to their waists in water, as Ireland put it, they were sitting or kneeling down on the raft.

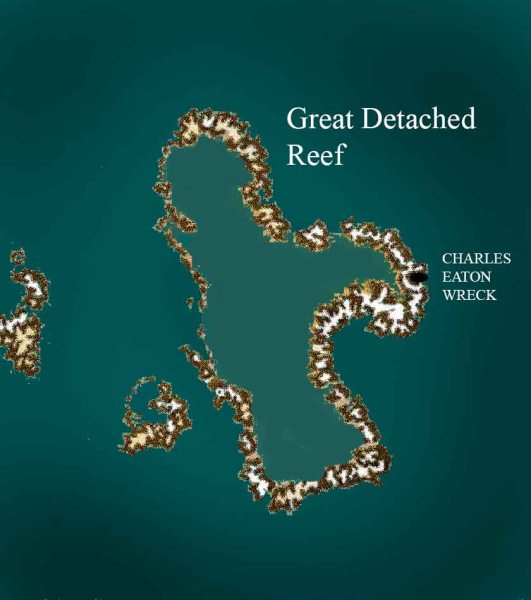

- Possibly the other side of the large lagoon at the centre of the Great Detached Reef.

- Ireland’s estimate of their number increased over time to 15 or 20. In one account, Ireland was quoted as saying two canoes came out to meet them.

- John Ireland, The Shipwrecked Orphans, New Haven: Babcock, 2nd edn, 1845, p. 19. Unless otherwise indicated, all quotes in this chapter have come from this book.

- See J. Lort Stokes, Discoveries in Australia . . . , vol. 1, Australiana Facsimile Editions no. 33, Adelaide: Library Board of SA 1969, pp. 362–63 for a complete description of the island now called Boydang.

- In another version of his story, given to Tigris commander, young Ireland said that they did have some arms with them but were too exhausted to post a watch. It cast the chief mate in a poor light, however, by implying that he had been careless, and that may be why the lad subsequently made no further reference to weapons.

- ‘Voyage in search of the survivors of the Charles Eaton’. Tales of Travellers: or, A View of the World. vol. 1, no. 56, Saturday, October 28, 1837, pp. 441–43.

- Capt. C. M. Lewis, Nautical Magazine, vol. VI, 1837, p. 658.

- Sydney Monitor, 19 Oct. 1836.

- London Times, 31 Aug. 1837.

- Ireland p. 29.

…. … ……. … ..

…

Chapter 14: mysterious Pullan

Pullan is a low sandy isle with trees and bushes growing on it, a short distance from Boydang. When their canoe arrived there, Ireland saw Portland, the ship’s dog, running along the beach. Next, he saw George and William D’Oyly. A native woman was carrying William but he would not stop crying. George, however, was calm and he came down the beach to the canoe in which Ireland was sitting. ‘What has become of your father and mother?’ Ireland asked. ‘The blacks have killed them,’ George D’Oyly replied, ‘and the captain, and Mr Armstrong, and our ayah.’ He said that he and his little brother were all that remained alive.

Ireland could see cabin doors used in the construction of the first raft decorating some of the canoes. The natives had attached them with great care and they were clearly prized. In the interior of the sandy isle, there were a number of open-sided shelters, within which the ship’s boy recognized several articles of clothing. There was Montgomery’s watch and white hat, and the gown worn by Charlotte D’Oyly when she left the wreck.

Nearby, a number of decomposing heads were hanging by ropes from a pole stuck in the ground. Charlotte’s head was easily identified because some of her long hair was still on it; another he knew as Captain Moore’s face. Ireland spoke to George D’Oyly again. ‘The little fellow gave a very distinct account of the dreadful transaction,’ he later stated. ‘He said he was so frightened when he saw his father killed by a blow on the head from a club, that he hardly knew what he did; but when his mother was killed in the same way, he thought they would kill him and his little brother too, and then he hoped they would all go to heaven together.’1

The attack had been over very quickly. After several days and nights on the raft, the first party had landed on one of the islets, probably on the side facing the Barrier Reef. Pullan is the largest cay in the group labelled by Captain James Cook as the ‘low sandy isles’. It has the tallest vegetation and to the thirsty party on the first raft it would have offered the best prospect of finding water.

It is probable that the people on the island had spotted their raft and sent a canoe out to intercept them. The canoeists would have been friendly and escorted them back to Pullan. The sudden arrival of white people always aroused genuine excitement and curiosity. The women in particular had probably stroked their clothes and hair and fussed over the small D’Oyly boys. There is a good chance that the raft party lived for a brief time and their hosts remained friendly. They would have been utterly exhausted by their ordeal and overwhelmed with relief that they had actually made it to safe land.

Some of the men on the first raft were armed. Based on Ireland’s various accounts we can be reasonably sure that there were men in the party who had a cutlass or knife and there’s a good chance that the two captains, Moore and D’Oyly, had at least one pistol each. What the D’Oylys, Armstrong and Moore should have guessed is that the Torres Strait islanders were obsessed with iron in any shape or form. It was number one on their wish list. They had stumbled across a party of islanders on a fishing expedition, but they were also on the lookout for trade items. The one thing that they desired most to possess was the white man’s ‘magic stick’, the iron object that made a loud noise when you pointed it at someone and that person died from a wound either instantly or very soon after. As a trade item, it was priceless, despite the fact that they had no idea how to use it or any understanding of how the ‘magic’ worked.

The weapons the castaways carried may also have meant that they were potentially dangerous and unpredictable and on no account to be trusted. Everyone except the two D’Oyly children was struck down from behind when their guard was down and instantly decapitated. George said that William had been in his mother’s arms at the time a savage head blow felled her, but was saved by one of the women, who rushed forward to snatch him up and afterwards took care of him. Another woman rescued George in a similar way. These women appear to have been surprised and shocked by the sudden and unexpected attack.

Ireland’s captors at Boydang and Pullan were from one or more of the islands in the Torres Strait. Captain J. Lort Stokes, who visited the cays a few years later, thought that the annual migration to some of the southern islands and sandy isles in Shelburne Bay off Queensland was a recent practice. The visitors, he thought, would make camp there around July and August because it was a favourite time for ships passing through the Barrier Reef. Every time a ship founded, they would hasten to the doomed vessel to strip her of iron, cutlery, cloth and anything else useful to them as trade goods.2 This view was a knee-jerk reaction to the Charles Eaton murders, for the islanders regularly went south for the fishing or turtle-laying season, sometimes remaining at Shelburne Bay for many months.