by Veronica Peek

(copyright holder: Veronica Peek) No AI training

…

…\\\

CHAPTER ONE: GOODBYE TO OLD ENGLAND

John Ireland went to sea in 1833 and became a famous ship’s boy. For decades, seafarers resigned to the terrors of typhoons and shipwrecks, linked his name to their worst nightmares and darkest fears. What happened to him had a tragic impact on Australia’s development as a nation, with frightful and bloody retaliation against that continent’s indigenous population, the inevitable consequence.

His story began to unfold in September 1833, when he walked through London’s streets to St Katharine’s Dock on the River Thames. At one of the dockyard’s moorings was a new barque in need of a boy to assist with the fit out and John had just been hired for the job. He was leaving behind his parents, George and Charlotte Ireland,1 at Stoke Newington,2 a village about three miles from the London post office on the verge of becoming a suburb. Wealthy merchants had discovered it as a rural retreat close to the city, and were lining its main roads with mansions. John’s parents, however, lived at 7 Barn Street,3 one of the oldest streets in the village. Their home near the corner of busy Church Street was part of a row of workers cottages. By 1832 the entrance to St Mary’s parish school was in Barn Street, a few doors from the Ireland house. It taught about 110 students at any given time, in an antiquated building shaded by trees.4

John probably did receive some education, yet his numeracy and literacy skills were poor. Dispatching sons of employment age to the merchant marines was a stock solution for cash-strapped parents, willing to ignore all that talk of savage beatings and watery graves. More often, the boys themselves had dreams of escaping quiet schoolrooms or raucous slums for a sailor’s life on the waves.

John was born on Christmas Day, 1818, and christened on 17 January 1819 at the old St Mary’s Church in Stoke Newington.5 He would later describe his parents as ‘aged’ (Sydney Herald 27 Oct. 1836) but in 1833 they were still in their thirties.6 George was a bricklayer, making a living from the new housing estates springing up in the area. He had five surviving children to support, ranging in age from John, who was approaching 15, to baby Eliza.7 His oldest son, George Jnr, was already an apprentice printer.

When John passed through St Katharine’s gate and saw the Charles Eaton for the first time, he had no reason to be displeased. She was a fine-looking barque, registered at 314 tons to carry 350 tons burthen,8 and was about to embark on her first real trading venture to the Australian penal colonies, having just arrived from a shipbuilding yard at Coringa, near Madras in India. She was named after Captain Charles Eaton, a former port master at Coringa.9

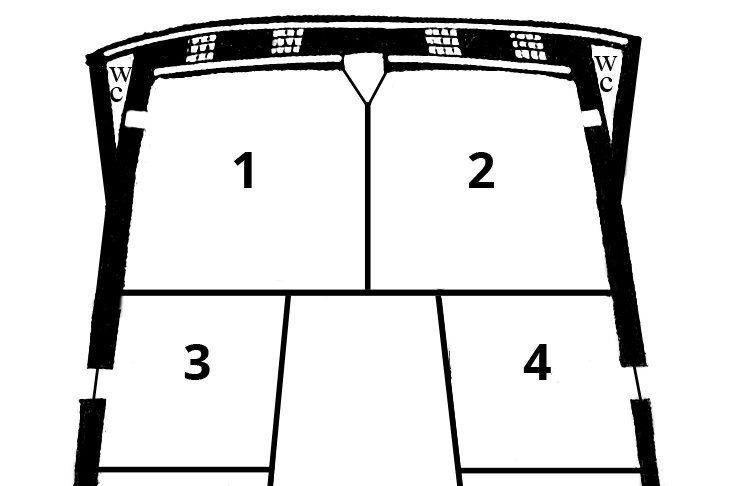

Advertised for sale soon after her arrival in London, she was described in the Guardian and Public Ledger (6 Sept. 1833) as having: “two flush decks, forecastle, bust head and quarter galleries, and is coppered to the wales in chunam [lime plaster] and felt”, the latter two being a common base for the copper sheathing of hulls. Her most attractive feature for first-class passengers was two quarter galleries, common on the large merchant ships servicing the Honourable East India Company (HEIC), but much less so on small merchant vessels the size of the Charles Eaton. Externally, they added extra decorative touches to the sides of the ship’s stern; internally they were usually tiny windowed WCs (water closets) with their toilet holes projected out over the sea. They were an extra luxury and could only be used by the occupants of the two largest poop cabins at the stern.

The respectable shipping company, Gledstanes & Co, accustomed to such features on India-bound ships perhaps, wasted no time in adding the India-built Charles Eaton to their fleet. She was lovely to look at and acceptable by the standards of her day, but she was not particularly seaworthy. British-designed merchant ships had deep, flat-bottomed hulls and holds capable of carrying cargo well in excess of their registration. When blown by the wind towards a lee shore or reef they responded slowly to any efforts to alter course, with potentially dire consequences for all aboard them.

John was one of the first of the new crew hired for the forthcoming voyage, his wage being no more than a few shillings a week.10 Since her arrival from Coringa the barque had been without a master. Captain Frederick George Moore, ex-EIC, had now filled the vacant post. John was the apprentice steward but in the meantime, he had to run messages, scrub decks, stoke fires and fill water casks. As far as his employers were concerned, he was a cabin boy, with whatever additional duties that role entailed. The rest of the crew came aboard when departure was imminent. Tom Haviside was the shipping agent and he placed the following notice in the 5 October 1833 edition of The Times:

For Van Diemen’s Land. – To sail on the 1st of November direct for Van Diemen’s Land and Sydney, the fine new teak ship Charles Eaton, burden 350 tons, F. Moore, late of H.C.S., Commander—lying in the St. Katharine Dock. This ship has superior poop accommodation, and 6 feet 6 inches heights between decks, having been built expressly for passengers, is well manned and armed, and carries a skilful surgeon. For freight or passage apply to the Commander, on board; or to T. Haviside and Co., 147 Leadenhall street.

Gledstanes & Co., the barque’s new owner, already had a fleet of East Indiamen servicing India and China.11 The Charles Eaton was its newest and smallest vessel and the right choice to test the Australian market.12 The broker began advertising her with great vigour but passenger bookings were slow.

One cabin passenger who did book early was a young, London-based lawyer, George Armstrong.13 Irish-born Armstrong was about 25 years old and acquainted with Captain Moore through Gledstanes or a mutual friend.14 He was planning to set up a practice at Canton in China. Taking the long route via Australia aboard a potential client’s new ship was a smart move. Gledstanes was venturing into the lucrative Canton market and would need an agent there. Armstrong invested in a quantity of wine and added it to the cargo in the hold. He would easily sell all of it at Sydney.15

Throughout October and November 1833, the broker received bills of lading for cargo booked to the barque. A large quantity of calico bales and 410 lead ingots came from Messrs Gledstanes, Drysdale and Co.,16 a merchant arm of the owner company. It was common for ship owners to top up their holds with their own speculative cargo when there were insufficient paid consignments. Gledstanes entrusted its cargo to Captain Moore, who would sell or barter it as the opportunity arose. His background with the EIC’s merchant navy adequately equipped him for that role.17 Elsewhere in the hold were stacks of alcohol for Sydney – puncheons, cases, casks and hogsheads of wine, brandy and port.18 The rest of the space was filled with sundry cargo, ship’s stores and passengers’ goods, including quite possibly a piano. The Hull family of London had chosen the Charles Eaton for their emigration voyage to South Africa and Mrs Sophia Hull and her two oldest daughters were talented pianists.19

Then came the happy news that the Children’s Friend Society had booked steerage passages for 40 orphans to the Cape of Good Hope.20 The Society had already shipped six batches of children to Cape Town and was wasting no time in sending more.21 Only some of the children were orphans; many had one or both parents living. They had come to the Society because their parents were either destitute, negligent, or could no longer control them. Some of the boys already had convictions for petty offences, and the Society had rescued them from a reform school.22

Most of the boys, however, were coming from the recently established Brenton Asylum at Hackney Wick – a village adjacent to Stoke Newington – where they were given an elementary education, but also taught gardening, domestic chores and other useful skills such as basic bricklaying and carpentry. The Asylum also had ‘a rope-walk round the yard, and a mast; for the pupils were trained for sea’.23

One day in early December, John was climbing the barque’s superstructure of ropes and spars when he fell into the polluted waters of the dock. The chief mate, Frederick ‘Fred’ Clare, instantly dived into the water and saved him from drowning. John needed a hero and he got one. Thereafter he would never speak a bad word against the chief mate.24 Clare was 29 years old and a first-rate officer. He had travelled from India on the barque’s maiden voyage as the second mate, but since had a promotion to chief mate.25 His father was the Rev. John Clare, now widowed and semi-retired to the Wolverhampton Deanery in Staffordshire.26 The Rev. Clare’s loving influence made it inevitable that Christian faith would govern his son’s actions. One day the chief mate would make an excellent captain. In his present performance was that promise for his future.

The newly appointed second mate, William Mayor, was a Londoner with a sister who would soon be emigrating to Australia with her family,27 while the ship’s surgeon was listed on crew manifests simply as F. or R. Grant. Captain Moore, meanwhile, had been hiring his crew. Ten general hands signed on with their standard sea-kits – a pannikin, one or two utensils, a change of clothes and a thin straw mattress. Their identifying uniform was still their wet-weather tarpaulin, a tar-coated hat sometimes fashioned as a sou’wester. Their duck trousers were firm on the hips and loose at the ankles, while woollen pea jackets were comfortable for men who spent their working hours climbing rigging.28 Reputation branded them as uncouth. They had to put up with tough and tasteless rations and a fair amount of savage persecution from the captain and his mates on the quarterdeck. The cramped and crowded forecastle (fo’c’s’le) where they ate and slept was also a hotbed of gossip about the captain, the passengers and anyone who had some control over privileges. Shipboard journals, usually kept by passengers, have typically described ships’ crews as either decent enough as sailors go, or ‘as bad a set of lubbers as ever worked a ship’.29

In Leadenhall Street, not far from St Katherine’s Dock, there was at that time a wine shop and wholesaler partly owned by John Wardell. It catered for sailors and stevedores and Captain Moore was a regular customer. So much so, that John Wardell and his brother, William, were his closest friends. Ex-EIC Moore was accustomed to private trading and may have encouraged George Armstrong to do the same. On the 13 December 1833, he entrusted his last will and testament to the Wardell brothers.30 In it he left most of whatever he owned at the time of death to his ‘excellent mother’ if then alive, otherwise brother James if then alive, otherwise his two sisters likewise.

One week later, on 20 December, Moore apparently wrote and signed a codicil appointing William Wardell and a business partner, Alex Gibbs, as the executors of his will. William Wardell would later say of Moore that he was a man of ‘known intelligence and enterprise’.31 The image that emerges from Wardell’s own sworn version of events is rather that of a man who was pre-occupied with finalizing his private affairs when he should have been preparing his ship for departure.32 Moore had formerly been a second officer aboard the East Indiaman George IV,33 but had recently left the Company’s service, voluntarily or otherwise. The EIC was about to lose its trading monopoly over India and China, and was already selling off merchant ships and sacking their seamen and officers, in anticipation of the inevitable reduction in its trade. Moore had returned to London and taken rooms at 26 Charles Street, Saint James Square. He was a middle-aged bachelor, and lived alone.

For a period of about 13 years, from 1830 till 1843, the aforementioned William Wardell was the proprietor of the Equestrian Coffee House at 124 Blackfriars Road, Surrey, usually with the help of business partners who came and went, doubtless taking what was left of their investment with them. It was in the same building as the Surrey Theatre, which hosted equestrian and circus displays for a time, hence the name. Like many coffee houses, it was also run as a gentlemen-only club for its own regular clientele, with club facilities and private rooms. Captain Moore would have been a comparatively solitary figure, a stranger in his home city after so many long absences at sea. It’s easy to understand why he was attracted to Wardell’s coffee house.

The young Irish bachelor, George Armstrong, may also have been a newcomer to London in search of compatible company at the coffee house. His friendship with the older and more worldly ship’s master may have blossomed over pots of ale at ye olde Equestrian. In any event, all thoughts of a London practice were abandoned. Armstrong chose instead to embark on an exciting and life-changing adventure with dreams of amassing a fortune from China tea, perhaps with the help of a few hometown Irish investors.

It had taken Moore only a few months to find work as the master of the Charles Eaton. Ship owners were finding it difficult to hire experienced men to captain their ships on voyages to Australia and were snapping up ex-EIC officers. It was a big promotion from second officer to ship’s master, especially for someone who had never been to Australia. Moore did, however, buy a copy of Horsburgh’s 1832 chart Passages through the Great Barrier Reef. He was worried about the accuracy of some of the charts for his forthcoming route. That sense of his own mortality is reflected in his will and testament, with its emphasis on past sins and God-willing salvation. He described no specific assets in it, apart from £400 to his brother, but EIC ships officers usually made a good second income from private trade. The last-minute scrappy codicil seems dodgy and may have been dreamed up to expedite the will for the benefit of Moore’s aged mother. You could also argue that it simplified the payment of creditors’ claims. Gledstanes knew nothing of it and continued to assume that they were Moore’s executors.

On 19 December 1833, with the winds finally favourable, the Charles Eaton sailed. The waifs from the Children’s Friend Society had boarded at London on 10 December, presumably with Mrs Sophia Hull, who would supervise the girls. The barque reached the Downs on 23 December, where she collected the bulk of her passengers.

The rest of the passengers for Cape Town and Australia now embarked, bringing with them their portable trunks, bedding, washbasins and other items recommended by the booking agent, such as sand and sandstone bricks, used for scrubbing down steerage decks. The bulk of their larger baggage had been loaded at London. The waifs numbered 18 girls and 22 boys and they ranged in age from 9 to 14. At least an additional 13 steerage passengers, including children, were going to Australia, although the real number was probably higher. Published passenger lists for steerage were sketchy at best.34 Most of them had travelled to the coastal village of Deal, in Kent, booking into boarding houses until it was time to board their ship, lying at anchor in the Downs, the roadstead for the English Channel. On any given day, there were usually dozens – but sometimes hundreds – of masters and commanders patiently waiting for the right winds to blow their ships safely through the dangerous waterway.

Sophia Hull probably embarked at London, while her husband, Henry, their eight children and Henry’s sister, Katharine Hull, embarked at Deal.35 Sophia was supervising the female juveniles from the Children’s Friend Society and had already hired one of them as a servant, while another girl, having presumably just lost or given up her own infant, was engaged as a wet nurse for Sophia’s baby.36

After a two-day stopover, the Charles Eaton weighed anchor for the Channel. Christmas day – and John’s 15th birthday – was passed quietly while they were still off the village of Deal, with many of the passengers too busy vomiting into their washbasins to care tuppence about special treats. They were too seasick to do anything at all, let alone cook and eat a rich pudding.37

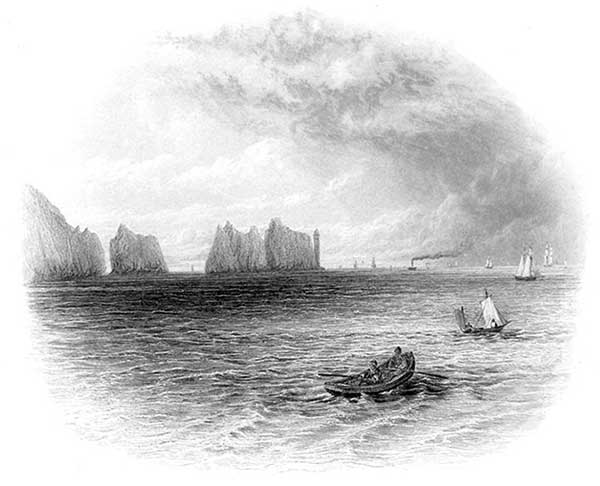

On 27 December the barque arrived at Cowes on the Isle of Wight, but was detained once more by unfavourable winds. Eight days later she quit the port, and was passing by the rocky outcrop known as the Needles when she collided with a schooner, which struck her across the bow, breaking off the bowsprit mast. ‘This accident caused great alarm among the passengers,’ commented the cabin boy, John Ireland, many years later, ‘and more especially among the children.’38 Well yes but the news when they received it in London must have alarmed the Messrs Gledstanes as well. There was nothing they could do about it though, except cross their fingers and hope they had hired the right master.

The accident forced the barque back to Cowes until the ship’s American carpenter, 33-year-old Laurence Constantine, had repaired the bowsprit and replaced the jib boom. As for the schooner, she was beyond repair. She made it back to Cowes but never put to sea again. The unexpected delay made it inevitable that some of the passengers would make up shore parties and put one of the small boats to use as a ferry. Captain Moore came back one day with a Newfoundland dog called Portland. As ship’s dogs go, he was a good choice. Newfoundlands are large and shaggy, but also intelligent, docile, and outstanding long-distance swimmers, known to have saved people washed overboard. The ship carried the usual caged livestock, but Portland would have ranked much higher in the entertainment stakes with the children.

For a vessel to have an accident while leaving port on a maiden voyage was a particularly bad omen. There is no reason to believe, however, that while the children were aboard it, the barque was anything other than a happy ship. The voyage was their last chance to savour the remnants of their childhood. Unfortunately for the young seafarers there were further delays when storms lashed England’s southern coast, forcing all ships to take refuge in ports.39 For the seamen, dressed in their waterproof hats and jackets, the daily routine of rotating four-hour watches continued unabated. For the passengers, it must have been a torture of boredom and discomfort. Only when the swells had moderated would they have ventured up on deck, to stretch their limbs and blink at rain-drenched Cowes.

When John Ireland had hugged his baby sister, Eliza, before his ship sailed, it really was a last farewell. While he was still sogging it out in Cowes, Eliza died aged 16 months.40 Perhaps that drenching winter was the death of her. It would be many years before the cabin boy caught up with the news. His suffering parents had now buried two daughters called Eliza in the graveyard at Stoke Newington’s St Mary’s church.

On 1 February 1834, the barque finally got under way again. She arrived at Falmouth in Cornwall four days later and loaded more cargo, plus at least one more steerage passenger. Eight days later the barque was underway ‘with a good wind, and every prospect of a happy voyage,’ according to John.41 What joy and relief for everyone but especially for the captain, who had to account for expenses. It had taken his ship seven weeks to quit England’s shores and there were well over 100 people on board, rapidly eating their way through the rations.

Header Image: Oil painting (1841) by John Wilson Carmichael, commissioned by William Bayley, the uncle who subsequently adopted and raised William D’Oyly. Portrays the moment when five canoe loads of Murray islanders escorted William out to the colonial schooner Isabella. Held by the National Gallery of Australia. I have taken the liberty of reproducing it here in what I hope is its original, unvarnished colour tones.

Notes to Chapter 1

- UK Census, 1841.

- Ireland’s London deposition, The Times, 31 Aug. 1837.

- Ireland, The Times, 31 Aug. 1837.

- The 1848 tithe map for Stoke Newington has a good image of Barn Street and its little worker cottages. John described it as being on the corner of Church Street, which locates it almost exactly.

- International Genealogy Index (IGI), St Mary’s birth and christening records.

- Sydney Herald, 27 Oct., 1836.

- Birth and baptism records from St Mary’s Stoke Newington, give us the following offspring for George and Charlotte in 1832: George, born 1817; John 1818; Eliza 1824, d. 1825; Charlotte 1826; Mary 1828; James 1830; Eliza 1832 (died 1834).

- Lloyd’s Register of British and International Shipping, 1834. Microfiche.

- ‘India Shipping’, Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register for British and Foreign India, China and Australias, vol. XVI, 1834, pp. 181–82. The barque was named after Captain Charles Eaton, a former ship’s captain, trader and owner of several ships. When he gave up the seafaring life he settled ashore as the Port Master at Coringa, a town in the south of India to the north of Madras (Chennai). He died there in 1827. Eaton’s son, Captain Charles W. Eaton, took over his father’s role as Coringa’s Port Master from 1828 until 1838, when Coringa was completely destroyed in a cyclone. He was the part-owner of at least three merchant ships. In addition, one of Eaton’s daughters was married for a time to a ship-builder at Coringa. Under the command of Captain Fowle, the barque arrived in London with 1000 chests of indigo worth about £45,000. On 14 June 1833 ‘Lloyd’s Shipping List’, had noted that: ‘The cargo saved from the James Sibbald, wrecked off Coringa, has been reshipped per Charles Eaton’.

- A weekly wage of 7s 6d was paid to ship’s boys hired as ordinary seamen. See ‘Letter to Editor’ from Captain W. S. Deloitte, The Times, 2 Sept. 1837.

- See the London Times, 24, 26 & 29 Aug. 1872, for the story of Gledstanes’ collapse.

- A list of ships owned by Gledstanes in 1833–1834 can be gleaned from the ‘India Shipping’ pages of the Asiatic Journal and Monthly Register . . . for the years 1834–1836.

- Sydney Monitor, 5 July 1834 also lists a Mr William Young and a Lieut Bullock as being ‘in the cabin’ on her arrival at Hobart Town. They were not on the passenger list ex-London and probably boarded at the Downs.

- William Bayley file, letter from unknown writer to Bayley, 25 Dec. 1835. Dixson Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, A1074. The writer’s name has been almost covered over, but the address is given as Rathicar in Ireland.

- ‘Import Trade List’, Sydney Herald, Supplement, 21 July 1834.

- Thomas Wemyss, Narrative of the Melancholy Shipwreck of the Ship Charles Eaton, 2nd ed., Stockton-on-Tees: J. Sharp, 1884, p. 6.

- Allan E. Bax, ‘Australian Merchant Shipping, 1788–1849’, Royal Australian Historical Society, Journal and Proceedings, vol. XXXVIII, part VI, 1952, pp. 274–75.

- Sydney customs list for barque included: 400 pigs lead, 5 puncheons and 10 hogsheads brandy, 3 casks and 22 cases wine, 1 trunk of boots and shoes, 37 bales of woollen cloths, 7 cases of cambrics and calicoes (Captain Moore); 10 hogsheads porter (Campbell & Co.); 6 casks and 12 cases of wine (George Armstrong).

- Email from D. Morris, a descendant of the Hull family, to the author.

- According to Ireland’s account, The Shipwrecked Orphans, New Haven: S. Babcock, 2nd edn, 1845, p. 7, the children were bound for Hobart Town. However, they were definitely delivered to Cape Town.

- Captain Edward Pelham Brenton founded the Children’s Friend Society in 1830. He opened the Brenton Juvenile Asylum in Hackney Wick, where orphaned, pauper or ‘at risk’ boys were taught agriculture. In 1834 the society opened a home for girls at Chiswick where they were taught domestic service. From 1832–1838 the society sent a large number of children to South Africa, Canada and the Swan River settlement in Western Australia. When the Society was forced to close in 1839 as a result of public criticism, Captain Brenton died soon after, from grief and disappointment.

- Charles Fores, Practical Remarks on the Education of the Working Classes; with an account of the plan pursued under the superintendence of the Children’s Friend Society at the Brenton Asylum, Hackney Wick, London: S. W. Fores, 1835.

- Sophia Elizabeth De Morgan, Mary A. De Morgan ed., Threescore Years and Ten . . . , New York: Cambridge University Press, 1895, digitally published 2011, pp. 193–94.

- Ireland, The Shipwrecked Orphans, p. 3.

- His father was not aware that he had been promoted and assumed he was still the second officer. See William Bayley file, letter from Clare to Bayley, 18 Aug. 1836, Dixon Library, State Library of New South Wales, A1074.

- Frederick Clare: christened 8 April 1804 at Bushbury, Staffordshire, fourth of seven children born to Rev. John Clare and his wife, Ellen. Source: International Genealogical Index (IGI). He was raised with his siblings in the vicarage in Sandy Lane, adjacent to the Bushbury church. His father was also the vicar of Wednesfield and a JP. In 1827 Rev. Clare moved to North Street, Wolverhampton, where he died in July 1839.

- Possibly christened 1808 and aged about 25 but not confirmed. Source: IGI. William Mayor’s sister Elizabeth married Henry Bull in 1832. Source: IGI.

- See Richard Henry Dana, Two Years Before the Mast, London: Heron Books, 1968, p. 1 for a description of a sailor’s clothing that corresponds with drawings of sailors produced in 1837 to illustrate the Charles Eaton story.

- Sir John Herschel, Herschel at the Cape, David S. Evans et al (eds), Austin and London: University of Texas Press, 1969, p. 9. Extract from shipboard diary, 1834.

- Moore’s new will and codicil, held at the UK’s National Archives.

- Wemyss, 1884, p. 16.

- Moore’s new will and codicil, UK National Archives.

- Wardell’s sworn affidavit in relation to Moore’s will and codicil. UK National Archives.

- Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 17 July 1834 and post for list of names.

- Email from D. Morris, a descendant of the Hull family, to the author.

- Geoff Blackburn, The Children’s Friend Society: Juvenile Emigrants to Western Australia, South Africa and Canada, 1834–1842, Access Press: Northbridge, Western Australia, 1993. p. 171.

- Email from D. Morris, a descendant of the Hull family, to the author.

- Ireland, The Shipwrecked Orphans, p. 4.

- The shipping news columns of the colonies’ papers show that all of the ships destined for Australia at that time arrived much later than expected.

- https://www.ancestry.com.au/

- Ireland, The Shipwrecked Orphans, p. 7.

…

…

CHAPTER TWO: A SHIPLOAD OF CHILDREN

It took almost three months to reach Cape Town, but those aboard the barque soon settled into the routine of the Atlantic leg of voyages to the south. We can reduce most accounts of such voyages to a catalogue of common experiences. There was usually at least one severe storm while skirting the Bay of Biscay in winter, for example, which terrified the wits out of passengers and any novices in the crew. Fortunately, the Charles Eaton crossed the Bay intact.

A typical day at the quarter galley, on the quarterdeck close to the aft hatch, began at first light. The galley crew had to scrape the ash pits, collect coal from the coal hole or bunker in the hold, light the stove fires and fill and boil the water coppers. Breakfast was usually from 8.00–9.00 am. Each person got a couple of ship’s biscuits (double-baked bread) and enough hot water for a small pot of sweet tea. Supper at night was the same. The main meal of the day usually consisted of salted meat and one or two vegetables, with some days set aside for soup instead. On most ships, all galley fires were out by 10.00 pm, along with any kerosene swing stoves and lanterns still burning below deck. It was a long working day for the steward and his young assistant, but they were exempt from the four-hour rotating watch and had the benefit of an unbroken night’s sleep.

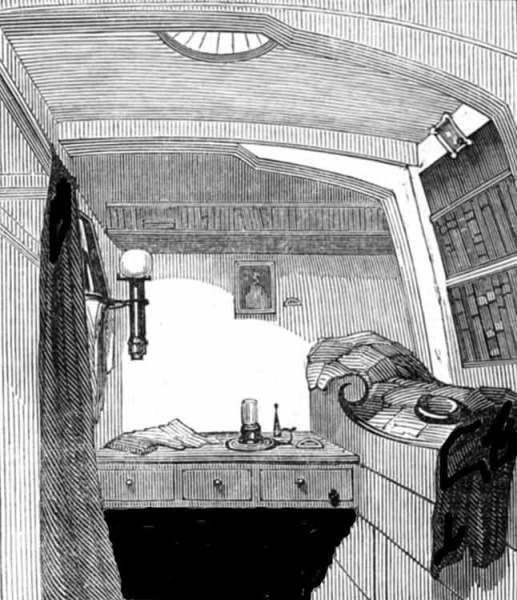

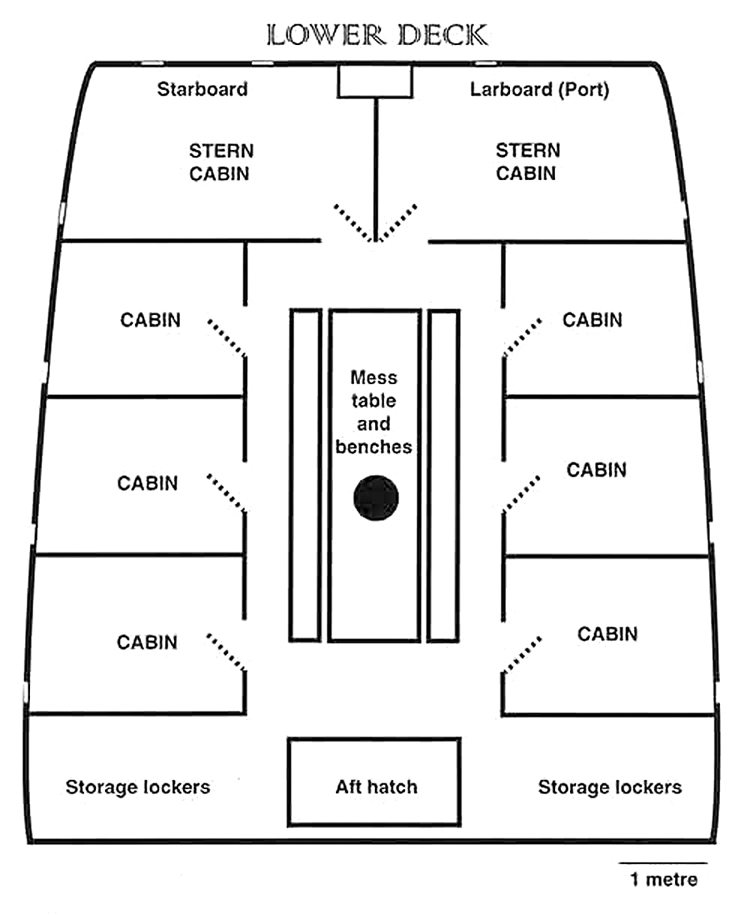

John’s chores were menial and required little skill. He was not particularly diligent and what little he did learn, he soon forgot. He would later admit that he gained nothing from the voyage that would stand him in good stead as an ordinary seaman.1 A sailor’s standard crafts remained a mystery to his untutored hands. The first-class cabins he helped to service were small and cramped but to those passengers quartered below deck, they were the pinnacle of luxury. Their status came from their exclusive isolation in the elevated poop.

The lower deck had a handful of tiny intermediate or second-class cabins at the stern, separated by a single bulkhead from the open-plan steerage for third-class passengers, which occupied the middle section. The Hull family probably had cabins in the intermediate section, so that Mrs Hull could supervise the girls. The fo’c’s’le at the bow doubled as a storage bunker and the sailors’ sleeping quarters.

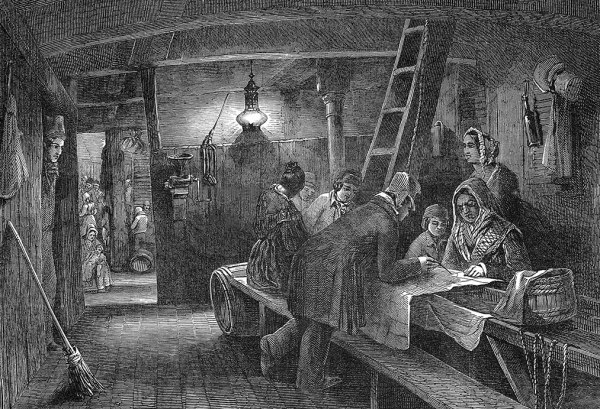

Keeping a large group of children amused and out of harm’s way on a long sea voyage was hard work for everyone. When the vessel was tacking across the wind, it was common for the slippery upper deck to be sloping at an angle of 45 degrees or more, so that even routine tasks such as lining up at the pantry for the handout of rations, or collecting boiling water from the galley stove, were fraught with danger. The boys had their own supervisor but the Society often provided nothing more than a slightly older youth, who acted more like a school prefect. The claustrophobic steerage was also a breeding ground for infections, all but guaranteeing that there would always be patients in the hospital beds.

There were two types of ship’s boys on merchant ships. Some, like John, were part of the cabin and galley crew. He spent most of his working hours lurking around the cabins and the quarter galley stove. If he applied himself, he might be a steward one day. Ship’s boys hired as general trainees spent more of their time tarring and painting, or aloft in the rigging. In time, they would earn their place in the fo’c’s’le as able seamen. For this voyage, there was one such lad, John Sexton, and the apprentice steward would describe him many years later simply as ‘a boy like myself’.2 John was always vague about this other ship’s boy and they were neither close friends nor bitter enemies.

Thomas ‘Tom’ Prockter Ching and William Perry were the mates’ apprentices and John always referred to them as the ‘two little midshipmen’.3 Ching was the youngest son in a middle-class family in Launceston, Cornwall, Ching being a traditional Cornish name. His father, John Ching, was a wine dealer and apothecary (pharmacist) whose patented treatment for worms had secured the family’s fortunes.4 Tom was 21 years old and diligently studying his way towards becoming a chief mate and, eventually, a master. Perry was probably of a similar age and, like Ching, had joined the ship at London.

The barque had no designated cook. The steward, William Montgomery, prepared basic hot dishes for the first-class cuddy (dining room), but the crew and lower deck passengers got measured rations and had to prepare their own meals. Montgomery wore a white hat to keep sweat and stray hairs out of the cooking pots. It was the common symbol of a ship’s cook but he was also in charge of all dining arrangements and provisions. He carried on his person a pocket watch to anticipate the ringing of the ship’s bell, which signalled the change of watch. Stewards and their assistants often kept themselves apart from the fo’c’s’le, largely because their sleeping hours were different, and sometimes bunked down in the cabin pantry.

When the Charles Eaton crossed the equator, the crew dressed up in makeshift costumes for the usual ceremony of paying tribute to King Neptune. They rigged up a sail between the masts and filled it with water. Any sailor or male passenger deemed to be disrespectful to the king got tossed in, clothes and all.5 According to a descendant, the Hull family males were spared most of the rough stuff but the steerage boys joined in and loved it. It was a good time in the tropical heat for them to have a rough scrubbing down and head shave.

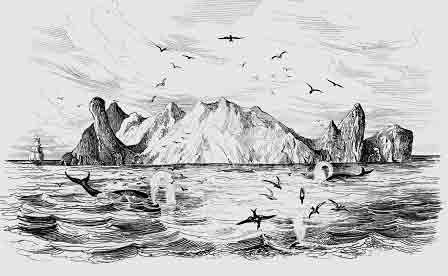

Once they had finally passed through the tropical calms, the sailors had to deal with the contrary trade winds. The time-honoured technique was to tack across the Atlantic towards the tiny island of Trinidade, about 700 miles ( 1125 kms) off the coast of South America, until they picked up the north-westerly trade winds, which carried them back across the Atlantic to Cape Town. This loop around the Atlantic added greatly to the length of the voyage but catching the trade winds usually shortened the sailing time.

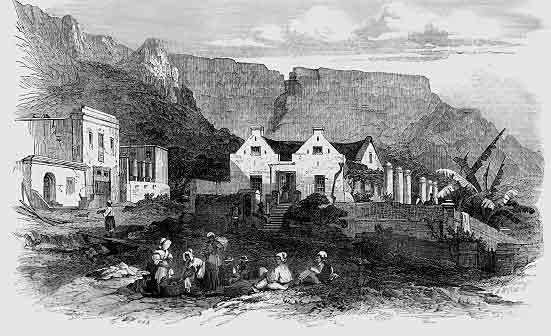

Table Mountain when it finally appeared over the horizon in all its barren splendour was a distant but welcome landfall. Tapering away to the south were the majestic ridges and sandy beaches of the narrow peninsula known as the Cape of Good Hope, lush with wild grasses and cultivated crops, dissected by many streams. Its botanical gifts to the world included watermelon, cantaloupe and geranium. There had been a time when weary seafarers claimed for it no equal on Earth. It is hard to imagine a finer approach to a seaport.

Cape Town, with its population of about 25,000, was a novelty for English visitors. The houses looked like they had transplanted from Amsterdam. Most had flat tops and looked roofless when viewed from a distance. Signs of industry were everywhere, in the hurry-scurry of foot and hoof traffic along the streets and in the valleys cultivated with orchards, grain fields and vineyards. The farm workers, however, invariably proved to be slaves. On 1 May 1834, the Cape Town government approved the emancipation of all of the British Empire’s slaves, with the date for their freedom set at 1 December 1834.6 The Cape colonists were alarmed, predicting an acute labour shortage. One easy solution quickly taken up by them was the importation of English children as apprentices. Their impact would prove to be negligible, however, given that there were many more slaves waiting to be set free.7

On that same day, 1 May 1834, the Charles Eaton arrived at Cape Town with her cargo of 40 children and the Cape colonists eagerly snapped them up. They had all arrived safely and in good health. They had many years of labour before they would be free of their apprenticeships, although the girls did have the option of early escape from their bondage through marriage. Apart from the rules governing their punishment and a tiny annual wage, the apprenticeship terms in British colonies were similar to those for transported convicts. Most of the girls found work as domestic servants, while the boys got jobs as farm hands, servants or trade apprentices. Two lads became boat boys, while one lad ended up as a ship’s boy aboard HMS Trinculo, at anchor off Cape Town at the time.8

A few days later, on 10 May, a local Cape Town resident, John Thomas Buck, sent a letter to the churchwarden of St Luke’s parish in London, and it ended up being published in The Times (14 Aug. 1834). Speaking of the children already delivered to the Cape, Buck remarked: ‘the elder boys have not conducted themselves well, and given much dissatisfaction to their masters, and many of the younger ones have proved troublesome’. His letter triggered the widespread criticism of the exportation of pauper children to the colonies that would ultimately lead to the dismantling of the Children’s Friend Society.

There was a vessel moored in Table Bay that now becomes relevant to those still aboard the Charles Eaton. The Jane and Henry was a South-African-owned, 146-ton brigantine-schooner, recently arrived from Liverpool. As schooners go she was tiny and old, with no rating of any value. She was a sturdy vessel all the same, with more than a dozen long sea voyages to her credit.9 On a previous voyage in 1832–1833 the schooner had attracted notoriety when it was found that the master, Captain Robert Latimer, was criminally insane. He was sentenced at Cape Town to six months’ hard labour.10 Fortunately the schooner was now commanded by Thomas Cobern,11 a master mariner and resident of Cape Town. She was loading cargo for the Australian colonies and may have been chartered by a consortium of Cape businessmen. Her cargo consisted of Cape wine in ‘pipes’, which already had a small market in Australia, plus some general merchandise, including china, shawls and pickles. Having discharged her cargo, the Jane and Henry would return to Cape Town via Batavia (now Jakarta). For a time, the small schooner would follow the same route as the Charles Eaton.

From Cape Town, Moore headed south to Australia, going as far as he dared below latitude 40°. When, after a cold but uneventful passage, his crew moored their vessel at Hobart Town, Van Diemen’s Land, their arrival was greeted with more interest than they might have expected – but there was a reason. Most ships’ captains collected local newspapers along their route and passed them on to reporters at their next ports of call. On 28 March, having received November editions of the London papers from a passing ship, the Hobart Town Courier had confidently announced that ‘the ship Charles Eaton, 350 tons, Capt. Moore, . . . may be daily expected with goods from London for this port.’ By mid-April, none of the expected merchant ships had arrived. Unaware of the storms that had delayed their departure from England, the colonists began to fear the worst.12

When the Charles Eaton finally turned up in mid-June and anchored just off the town’s foreshore in Sullivan’s Cove, a reporter from the Courier sought a reason for the long passage from England. Moore explained that he had been held up in England by storms but refrained from mentioning the collision with another vessel that had caused much of the delay. He was soon busy signing bills of lading for additional cargo to Sydney, including five cases of hats and one case of bonnets from a local milliner.13 He also got two more cabin passengers, Mr and Mrs Severin Kanute Salting, who had travelled from the London Docks aboard the brig Meanwell. Moore had a variety of consigned cargo for the port, including barrels of salted meat and fish for a ship’s chandler. He soon discovered, however, that Hobart Town was going through a brief economic downturn and was not particularly receptive to speculative cargo. He managed to sell some alcohol and the usual popular food items such as raisins and treacle for ships’ puddings, but not much else. The Jane and Henry’s captain had little luck in Hobart Town either, and soon sailed for Sydney. Moore did, however, have one more visitor. Captain Thomas D’Oyly of the Bengal Artillery was seeking passages to Sourabaya for himself, his family and his Hindu servant. The D’Oylys have left behind a detailed account of their lives, and the chain of events that brought them to that fateful moment. Many of the personalities introduced in the following chapter will re-emerge later to make their contributions to the wake for the voyage of the barque Charles Eaton.

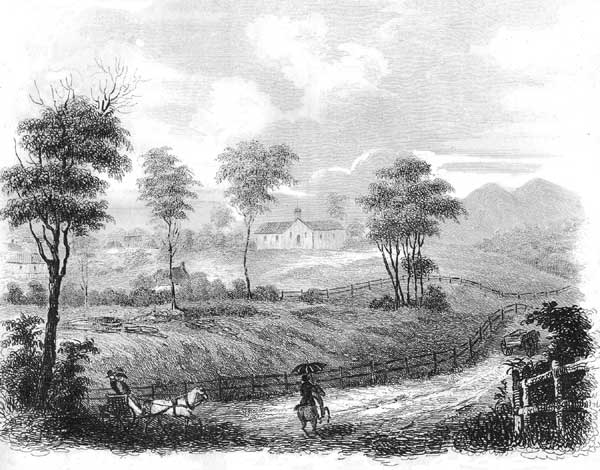

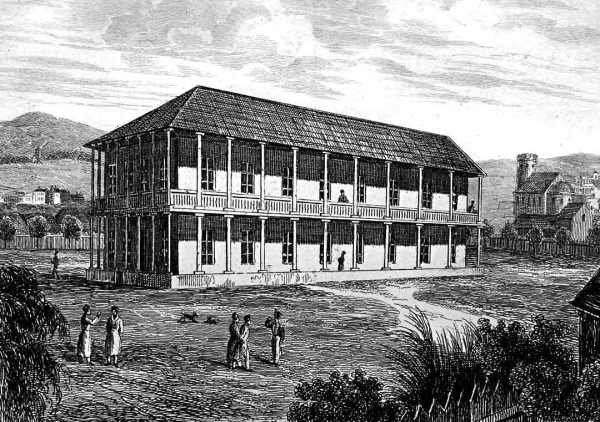

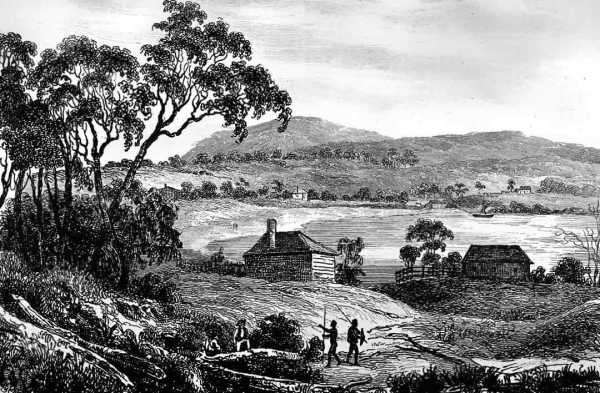

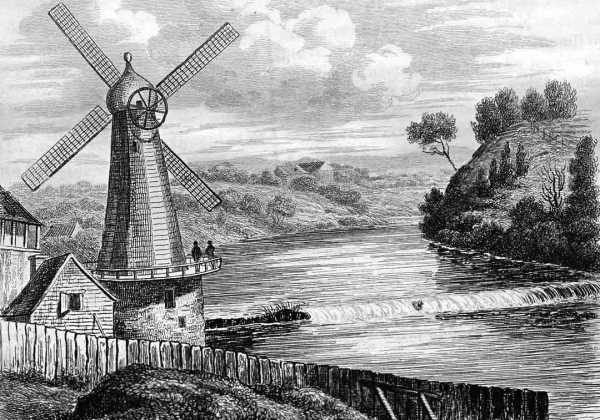

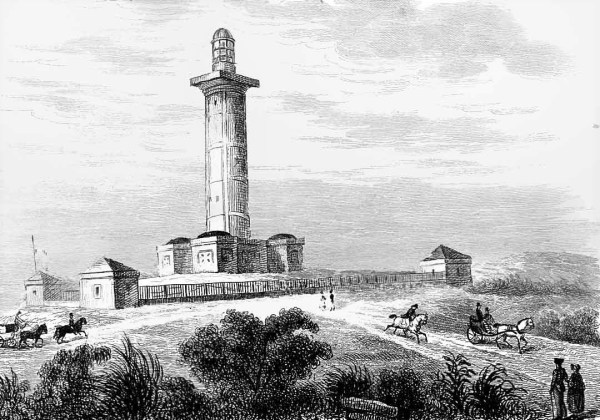

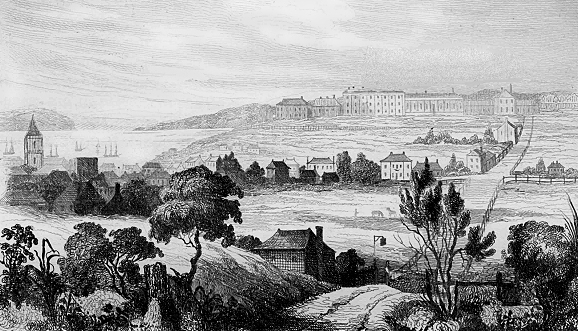

Some images of Hobart Town in the 1830s

A gallery of merchant seamen, in the outfits they would typically wear in the 19th century. Reimagined with research and the help of artificial intelligence.

Notes to Chapter 2

- Sydney Monitor, 11 Nov. 1836.

- Ireland’s London deposition, The Times, 31 Aug. 1837.

- William Bayley file, copy of statement by Captain Igglesden, Tigris, 31 July 1836, Dixson Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, A1074. His use of the word ‘midshipmen’ suggests that in common sailor’s parlance it was not a term restricted to apprentice officers in the navy.

- See Laurence Green, A Hollow Sea: Thomas Prockter Ching and the barque ‘Charles Eaton’, Ashprington, Devon: RGY Publishing, 2007, for biographical information about Ching’s family.

- Email from D. Morris, a descendant of the Hull family, to the author.

- John Fisher, The Afrikaners, London: Cassell, 1969, pp. 58, 99.

- Lacour-Gayet, Robert, A History of South Africa, Stephen Hardman (trans.), London: Cassell, 1977, p. 71.

- Geoff Blackburn, The Children’s Friend Society: Juvenile Emigrants to Western Australia, South Africa and Canada, 1834–1842, Northbridge, Western Australia: Access Press, 1993, pp. 170–71.

- Lloyd’s Register of British and International Shipping, 1834, microfiche.

- Hobart Town Courier, 23 Aug. 1833. The story of what happened on board the Jane and Henry on her voyage to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) in 1832 is an interesting example of shocking exploitation of pauper emigrants by a ruthless operator, with the additional hazard of a master and a chief mate who were psychopaths. Captain Larimer had been released from prison just prior to departure from Liverpool and was later described in contemporary accounts as criminally insane. The brigadine was confiscated by the Cape Town government to pay off debts and resold in time for the 1834 voyage to Australia.

- This spelling of Cobern’s name has been taken from Cape Town’s 1833 census. Other spellings include Cobairn and Coburn.

- ‘Domestic Intelligence’, Hobart Town Magazine, vol. III, no. 14, April 1834.

- Sydney Herald, Supplement, 21 July 1834.

…

…

…

CHAPTER THREE: THE D’OYLY’S OF INDIA

Just outside the village of Kirby Wiske, near the town of Thirsk in Yorkshire, there once stood a very old stone-built house, called Sion Hill. The estate and all its structures fell into disrepair until Mr Edward D’Oyly bought it in 1799.

Captain Tom D’Oyly of the Bengal Artillery, briefly introduced at Hobart Town in the previous chapter, was Edward’s son. Born with his twin brother, Edward Jnr, in 1794, he moved with his parents to Sion Hill in 1800. Edward D’Oyly and his wife, Hannah, spared no expense in renovating the hall and adding new wings, landscaping the grounds with gardens leading down to the River Swale. In time Sion Hill was reborn as one of the most attractive estates in North Riding, and its owners were considered by all to be ‘one of the happiest and most united of families’.1

The D’Oylys relished their life at Kirby Wiske for a number of years. Financially, however, they were struggling. In June 1808, D’Oyly placed a single modest advertisement in the York Herald offering the Sion Hill estate for sale but did not repeat it. This was followed soon after by run of family and financial tragedies. Edward Jnr wanted to become a mariner, so his father bought a large share of the huge chartered East Indiaman, Jane Duchess of Gordon, which had previously belonged to her master, Captain Cameron.2 The captain then obliged them by employing Tom’s 11-year-old twin brother as a midshipman.

In March 1809, a convoy consisting of 15 East Indiamen and one brig-of-war was caught in a fierce hurricane south of the island of Mauritius that lasted for three days. Five of the ships, including the Jane Duchess of Gordon, sank with the loss of all lives.3 Edward was 13 when he perished. At about the same time, his older brother, James, died of a fever while still a cadet at Calcutta (now Kolkata) in India. Captain Cameron’s widow and 11-year-old daughter, Anne Cameron, visited Sion Hill when they heard the news. They found the family in a terrible state. Not only were they still mourning the deaths of James and Edward, but an ailing infant son, Josephus, would die within days.4 Edward and Hannah were hospitable to the captain’s widow and Anne Cameron exchanged letters with the eldest daughter, Elizabeth, for a time. Twenty-eight years later, Anne Slade (née Cameron) re-emerged to play an important role in the D’Oyly family’s history.5

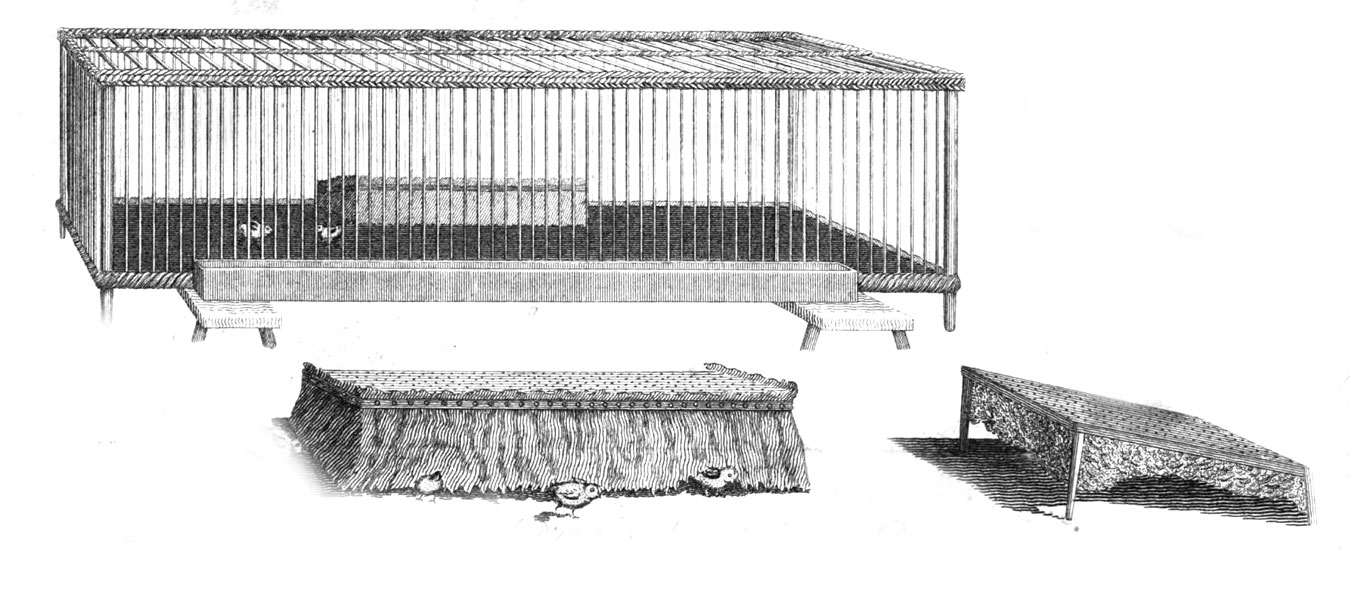

Edward and Hannah, with their dream of being ship owners now extinguished, had insufficient income from their estate. To their credit, they tried many ways to expand it. In 1808 Hannah, who was quite inventive, had set up a chicken farm and sold eggs and chickens to the local markets. She had a large stock of hens and roosters and came up with a new way to raise chickens that earned her a prestigious science award. She envisioned a future in which chickens could be commercially raised anywhere, including in city backyards, in cages with an artificial ‘mother’ hen. With a high survival rate, these healthy chickens would become free-ranging egg layers but also the cheaper meat of choice at the markets. Hannah D’Oyly was a woman ahead of her time. She was also one of the first people in England to commercially cultivate bull-rushes (on the Sion Hill estate) for the rush seats market. Estate workers had shored up the banks of the River Wiske with soil and willow trees to prevent flooding and the numerous holes they dug became artificial ponds, ideal for bull-rush cultivation.

Her husband, for his part, turned one of the farm sheds into a large machinery workshop well stocked with an array of tools. He had a gift for repairing his own machines and it wasn’t long before local farmers began bringing their broken machinery to him for repair. Hannah dispensed Christian charity but was also business oriented. Edward, however, was very sociable and well liked, and didn’t charge for his labour. He also generously employed far more local labourers than his estate could afford.

To the great chagrin of his children, Edward D’Oyly was broke.6 His solution was to asset strip and re-mortgage, until there were very few assets left. The begging letters that he wrote to his bank at that time make distressing reading. By 1815 he was too afraid to attend the Thirsk market for fear of running into one of his creditors. Tom, their oldest surviving son, escaped from the deepening misery at Sion Hill when he joined the Bengal Army in 1810, and was among the first intake of students at the EIC’s Addiscombe College near London.

Two years later, in 1812, he was posted to Bengal as a subaltern/fireman in the artillery.7 A relative, Sir John Hadley D’Oyly, the EIC’s Controller at Calcutta, and later his son, the enthusiastic amateur artist Sir Charles D’Oyly, took an interest in Tom’s career and promoted his merits in every quarter, introducing him into the highest echelons of Calcutta’s society. During his first year in Bengal as a ‘griffin’ or greenhorn, Tom lodged for a time with the baronet. He was the second ‘griffin’ to experience the hospitality of the baronet’s household, for his older brother, James, also enjoyed that welcome while a cadet in the Bengal Infantry. James joined his wealthy relative’s circle for a spot of hog hunting and died soon after from a fever thought to have been caused by an infected wound. Sir Charles would subsequently publish the illustrated burlesque poem Tom Raw the Griffin, which records some of the shared experiences of griffins like his two relatively distant and impoverished cousins.

In 1817, Lieut Tom D’Oyly finally took part in one brief battle and ended up in a safe staff position. Apart from that, he passed an uneventful eight years in Bengal until Charlotte Williams arrived on the scene.

Charlotte was the daughter of Henry Williams, for many years the Company’s commercial resident at the Commercolly (now Kumarkhali) station.8 In those days it was a river village in the low-lying and often flood-soaked region known as the Ganges delta.9 Today it is a major city in Bangladesh. Henry and his wife, Agnes, had two daughters, Charlotte (1796) and Fanny (Frances Sophia 1798).10 By 1800 they had parted acrimoniously amid claims that Agnes had been unfaithful, and the two girls lived at Russell Square in London with their wealthy grandparents. Charlotte’s grandfather, ship captain Stephen Williams, was a director of the EIC (1791–1804), while his wife, also Charlotte and sister of Sir John Hadley D’Oyly, was a former nurse to the two youngest of the 15 children of King George III, Prince Alfred (died aged two from a smallpox inoculation) and Princess Amelia.11

When Mrs Williams finally left the royal household, she maintained her ties with the royal family. Her brother-in-law, the wealthy banker and MP, Robert Williams, of Bridehead in Dorset, owned a fleet of East Indiamen and the family named one of them the Princess Amelia.12

King George III and Queen Charlotte were possessive parents and their six daughters did very little socialising outside their own households.13 Princess Mary, the Duchess of Gloucester, was their third daughter and she doted on children, making it inevitable perhaps that she became young Charlotte’s favourite royal. The impressionable little girl grew to womanhood treating Princess Mary as a much-loved friend. The princesses were often delightful companions but they could also be demanding and thoughtless. Given their royal status, it was only to be expected. The same traits in Charlotte were less easy to accept. There is no detailed description of Charlotte but there is a small bonus in knowing that her hair was brown-gold or auburn. In later years she would braid and/or twist it up into a coiffure with combs.14

In 1818, Henry Williams returned to England on leave and escorted his two daughters back to India. Their second cousin, Sir Charles D’Oyly, now the seventh baronet following the death of his father, was one of the Company’s opium agents, and he organised a ball at his palatial Calcutta home to introduce the two Williams girls to society. His other relative, Lieut Tom D’Oyly of the Bengal Artillery, was also a guest. Charlotte found Tom’s charms irresistible and their marriage, on 10 May 1820, united two branches of the D’Oyly family.

Tom was based at the Dum Dum artillery station, on an extensive plain four miles (seven kilometres) north of Calcutta. Married officers lived in spacious bungalows around a small drill ground, but Tom and Charlotte bought their own bungalow, at no. 29 Jessore Road, near the Dum Dum cantonment but off it.15 Children, when they began to arrive, were welcome distractions. Their first son, Thomas (Tom Jnr) was born in October 1821, followed by Edward in 1823 and George three years later.16

The D’Oylys weren’t wealthy so it’s likely that they borrowed money from a rich Indian money-lender to buy their large off-station bungalow. In status-conscious British colonial Calcutta it was all about keeping up appearances and many a young British officer ended up in financial straits when he couldn’t meet the interest on his loan. Tom, as main heir, expected something from his late father’s will. He got his share of the Sion Hill estate all right, but once it was sold and the multiple mortgages paid off there wasn’t a great deal of it left. Fortunately Charlotte had received a handsome inheritance when her grandmother died in 1813.

Both the real Lieut Tom D’Oyly and the fictional Lieut Tom Raw in Tom Raw the Griffin had scolding wives called Charlotte and in 1824, when the book was being written, they both had two sons, the oldest of whom was also called Tom. Each then had another son. The poem makes it clear that the baronet had little time for army wives. But Charlotte, who had always been proud of her relative’s achievements, may have been both puzzled and hurt by his satire. She may even have scolded Sir Charles or expressed her dismay. If so, then it had the desired effect. For the rest of his life Sir Charles did not publicly acknowledge any involvement with Tom Raw the Griffin. The book’s illustrations in particular attracted a lot of praise so it was quite a sacrifice on his part.

Tom’s oldest sister, Elizabeth, had married a conveyancing solicitor, William Bayley, of Stockton-on-Tees in Durham.17 When Tom faced the usual dilemma of sending his two eldest sons to England for their education, the Bayleys agreed to take them. Those leisurely years in Calcutta were ending, however, for Tom got a promotion to Captain and a posting to the Company’s ordnance at the Chunar Fortress, in the Mirzapoor district of northern Bengal. The promotion came at a price. Chunar had a reputation for being one of the hottest British stations in India.18 It is on the southern bank of the River Ganges, about 17 miles (28 km) southwest of the holiest Hindu city of Benares (now Varanasi).

During the D’Oylys’ time, there were about 1000 invalids19 stationed at Chunar. It was the Company’s invalid station, where they herded their chronically sick and wounded British soldiers, together with their families. They guarded an ancient and decaying fort that no one attacked. Some of the soldiers were old but most were young, victims of India’s cholera epidemics. Officers, however, enjoyed ‘the usual East Indian splendour’20 at Chunar, by which we can assume that they actually lived in an airy bungalow shaded by trees. Many of the officers stationed at Chunar were also invalids. Captain D’Oyly may have been unwell for some time. Additionally though, Chunar attracted a generous remote-station allowance, and he needed the money.

In August 1831 Charlotte gave birth to their last child, a son called William, preceded by the death of an infant daughter in 1829.21 When Charlotte fell pregnant with William, having already lost a daughter, she returned to her Calcutta bungalow for her confinement and William’s birth and refused to return to Chunar. A few months later, the D’Oylys received the news that Tom’s oldest sister, Elizabeth Bayley, had died suddenly at Stockton-on-Tees on New Year’s Day, leaving her husband to raise their five children alone, including a newborn son.22 William Bayley was now the sole guardian of their two eldest boys. Despite their brother-in-law’s reassurances, it must have occurred to them that this was an unreasonable burden.

The following year, Tom applied for overseas sick leave, on the basis that his health had suffered under Chunar’s heat. He was also running out of time. Every one of the Company’s officers and civil servants in India was entitled to two years of fully paid sick leave – and they invariably used their benefit. Tom’s choice of destination for his leave should have been obvious: go home to England and Tom Jnr and Edward, now aged 12 and 10. Yet he nominated Hobart Town in Van Diemen’s Land instead. It was an Australian penal colony but it had a mild climate, making it a favourite destination for invalids from India. Charlotte, who was ‘pining to be restored to her absent Children’23 shed many tears of disappointment. At the same time, the arrangement Tom and Charlotte had with William Bayley was very convenient for them. Bengal Army officers aimed to retire back to England on at least the full pension of a major, a goal they could only achieve after 25 years of service in India. If they retired early, they received a half-pension instead. Captain D’Oyly needed one more promotion and three more years in India and they would be financially set for life.

The family left Calcutta on 21 March 1833 with a ship’s hold stacked with furniture, plus crates and trunks of household goods. They disembarked at Port Louis on Mauritius for what would prove to be an extended sojourn. They posted their en-route letters to their sons from this port. The first ship to come along bound for Van Diemen’s Land was the Indiana, out of London. Her master, Captain Webster, had detoured to Mauritius to pick up a cargo of sugar. On 9 September 1833, the Indiana took on board a pilot for the final navigation up the Derwent River. Hobart Town (now the city of Hobart) when it finally came into view proved to be a charming replica of an English town. It was spring when they arrived and flowers were blooming under a soft southern sun. Within a week of their arrival, they not only had three assigned convict servants, they had already settled into a large, recently vacated, house in the little town of New Norfolk.24 Rental properties were difficult to come by in New Norfolk, particularly at short notice. Captain D’Oyly may have had, through their Calcutta lawyer, a local contact, a landowner called Richard Armstrong.25

New Norfolk is about 22 miles (35 kms) north-west of Hobart along what was, in 1833, an uncomfortably rough road. In those days it was flattering to its inhabitants to call the tiny settlement a town, since it consisted of little more than a handful of cottages scattered haphazardly around a church, a school, a hospital and a few fine houses and inns. For India invalids, however, it was ideal. It was an enchanting village with a moderate climate. It also had an excellent invalid hospital for settlers and convicts that dealt at that time with both physically and mentally ill patients. It was a long way from Calcutta to New Norfolk. Despite its curative qualities, only the most seriously ill India invalids bothered to make the effort to get there.

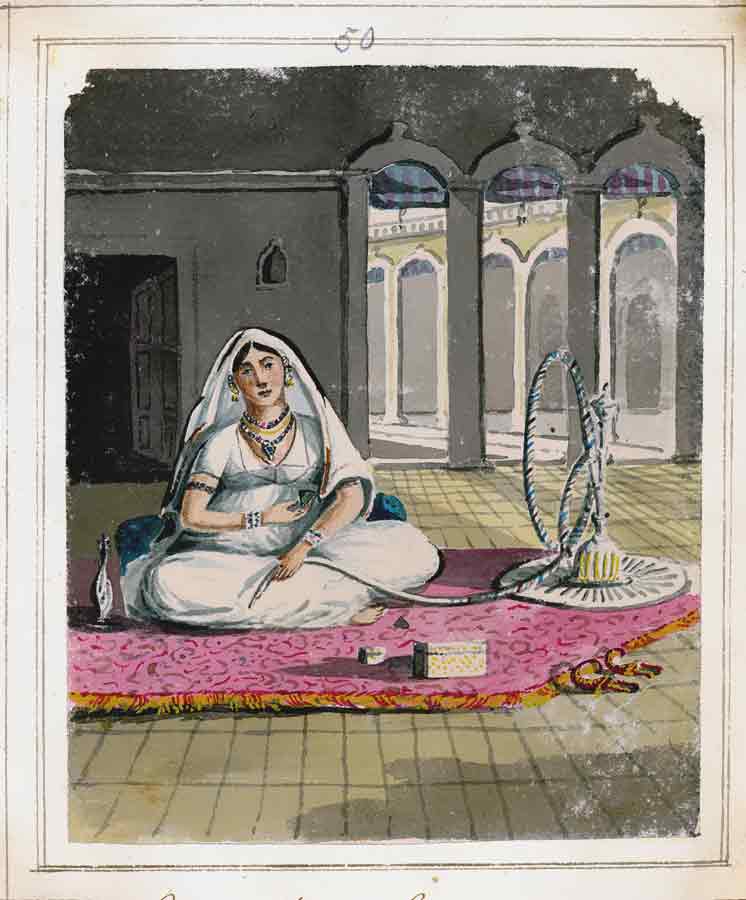

India invalids suffered from respiratory complaints often exacerbated by smoking the hookah pipe, and liver complaints caused by drinking too much alcohol in the sub-continent’s sapping heat. More seriously, bouts of cholera and chronic diarrhea had destroyed their health. They often moped and left it up to their spouses or friends to make the necessary decisions. Many of them wanted to return to England but their surgeons advised against it. The dramatic change of climate would have an adverse affect on their damaged lungs. Sick leave in England too often proved fatal. The East India Company’s own surgeons recommended the Australian penal colonies instead.26

Charlotte must have endorsed the decision to go to New Norfolk. Her husband had been a prolific letter writer to his friends and relatives in England, tiring them no doubt with copious details of his lifestyle in India. His pen was now still. It was left to his wife to exchange letters with William Bayley and their sons in England.

It does appear, though, that Charlotte was not completely forthcoming in her letters to her benefactor, William Bayley. The wage of an artillery captain in the Bengal Army was modest, yet the lifestyle the D’Oylys created for themselves in Van Diemen’s Land was extravagant for holidaymakers. The virtual bankruptcy of his parents at the Sion Hill manor in North Riding, Yorkshire, had made Tom frugal with his money. No one made that claim about Charlotte, who relished the lifestyle of a British memsahib in colonial Calcutta and was happy to duplicate it at New Norfolk. She had also inherited a large sum of money from her grandmother, Mrs Charlotte Williams, and was probably keen to secure a future for her four sons in one of the British colonies.

Theirs is not just the story of a family holiday in the backwoods of Van Diemen’s Land, with smoking wood fires and leisurely walks while Captain D’Oyly recuperated, although that was certainly a part of it. Was Bayley told, for example, that Tom and Charlotte had initiated the purchase of almost four acres of land on Warwick Street, in the centre of Hobart Town, previously owned by a carpenter called Montgomerie and already planted with fruit trees? (Launceston Advertiser 7 March 1845). Perhaps they intended to return and settle in the penal colony or perhaps it was a wise investment. Hobart Town’s reputation was growing and land values in the township were expected to skyrocket . Unlike officers in Britain’s own armed forces, Bengal Army officers were seen as mercenaries employed by a private company and had never been eligible for free land grants in Britain’s Australian colonies.

The house and grounds that the D’Oylys rented at New Norfolk must have been vacated by tenants or owners who were leaving the colony. Tom and Charlotte probably bulk bought almost everything the previous occupants couldn’t take with them, including farm animals and equipment. To this they added many precious and exotic possessions they had brought with them from India, with the expectation of entertaining in lavish style. By mid-May 1834, however, the captain was preparing for his own return to Calcutta. He handed all of their goods and chattels over to the local auctioneer, John Stracey, who placed the following lengthy and overly descriptive advertisement in his free and short-lived newspaper, the Trumpeter General, 27 May 1834:

“On Wednesday, the 18th June, and following days, commencing at 12 o clock, on the Premises, at New Norfolk, without reserve, MR. STRACEY, WILL SELL BY PUBLIC AUCTION, ALL the Valuable furniture, musical instruments, books, horses, carriages, plated goods, live stock, &c. &c., the property of Captain D’Oyly, who is about to return to India—comprising very handsome European made dining tables, 17 feet by 5, forming, if required, several convenient tables, very handsome dining room chairs, mahogany Cleopatra couch on casters, with mattress and pillows, mahogany footstools,, iron wood tea trays, hearth rugs and carpets of the most costly description, English and Indian manufactured mahogany bagatelle board, with mace, cue, and balls, an elegant backgammon box, with dice and men complete, a remarkably handsome and curious set of ivory men, breakfast, loo, drawing room, hall, lamp, camp, and bedroom tables, drawing room chairs, one pair of very splendid China jars, liquor case with cut bottles and plated stands neat tea and medicine chests, teak wood cheese stand, a superb ladies dressing case, fitted up with scent bottles, jug, basin, brush, trays, &c., with several drawers, compartments, and conveniences, large and handsome teak wood bedsteads, teak wood drawers, wardrobes, and clothes cupboards ; the whole of the bedding is the best that could be purchased. Fenders, fire irons, and fire guards, kitchen utensils all, nearly new. The China ware is of a beautiful and elegant pattern ; the cut glass desert [sic] service is splendid and costly in the extreme ; the dinner service is one of Spode’s best; the fowling pieces and rifles are in cases nearly new, by the first makers, and complete, with apparatus ; a set of Golf clubs are very rare ; the plated goods, candlesticks, and lamps, have been but little used; the piano-forte is by one of the first makers; the Stanhope is very handsome, built by Barton and Co, of London, with hood, lamps, and patent axle, colour, straw picked out black, has spare linings, boxes, caps, nuts, and new wheels; the phaeton has been little used and turns remarkably light ; the harness corresponds in neatness and quality with the carriages ; the saddles, bridles, and martingales are nearly new; the horses, pigs, poultry, bullocks, and husbandry implements need no comment till the time of Sale; the stock of wine is really superior and rare, and the porter will be found very good. The miscellaneous articles will comprise about two hundred lots, and are all very useful. The library contains many standard curious and valuable works elegantly bound. It can so very seldom happen in this part of the world, that an Auctioneer has the gratification to offer the public property of so truly valuable a description as Captain D’Oyley’s [sic], that comment upon its first cost, its elegance combined at once with the strictest regard to comfort, and the great care which has been taken of it might only tend to throw a doubt upon its great value ; suffice it therefore to say, that to those who may not wish to purchase, it will be a great treat even to take the opportunity of getting a sight of eastern magnificence at the time of sale, which will commence daily at 12 o’clock. The mode of payment will be cash for all purchasers under 25l. That sum and upwards, bills with two names, at three months.“

Phew! Clearly the family hadn’t been roughing it in Van Diemen’s Land. They were certainly leaving behind in the colony a lot of unfinished business. Eight months after their arrival, the Caledonia had arrived from Calcutta, with a letter for them containing the news that Captain D’Oyly had been promoted to a more senior position.27 With his health now seemingly restored, he was anxious to get back to work. Misfortune was on his side, for the barque Charles Eaton had also just arrived and she was bound for Calcutta via Sourabaya and Canton.

Anyone who did business with the D’Oylys at that time would have assumed they intended to settle permanently at New Norfolk and Hobart Town. Yet they abruptly auctioned all of their recent purchases, along with everything they had brought with them, and rushed to sail away upon the first ship heading in the general direction of Calcutta.

D’Oyly had just been informed of a duty promotion that would presumably have allowed him to buy a seniority promotion from captain to major. This had long been his aspiration and he was anxious to get back to Bengal before the post was offered to someone else. As yet, he had not formally resigned from his position with the EIC.

Charlotte wasn’t convinced that going back to India was necessarily the right thing to do. She would later admit to her brother-in-law, William Bayley, that a full retirement pension was their preferred retirement strategy but her husband’s health took precedence over financial considerations. She was already considering the possibility that Tom’s ill health might return in India’s oppressive heat. With her additional desire to be reunited with her two oldest boys, coupled with an equally strong wish to be back with her numerous relatives in Calcutta’s colonial splendour, she was conflicted and often tearful.

The letter from India may have forewarned them that the full annual pension the EIC offered to their military and civilian employees after they had completed 25 years of service in India would soon be available after only 23 years of service. D’Oyly had only to remain with the EIC in India for another eighteen months and if he played the right cards he would be eligible for retirement on the full annual pension of a major. Remaining in Van Diemen’s land would have meant a half-pension based on a captain’s salary. It was a big difference in retirement income.

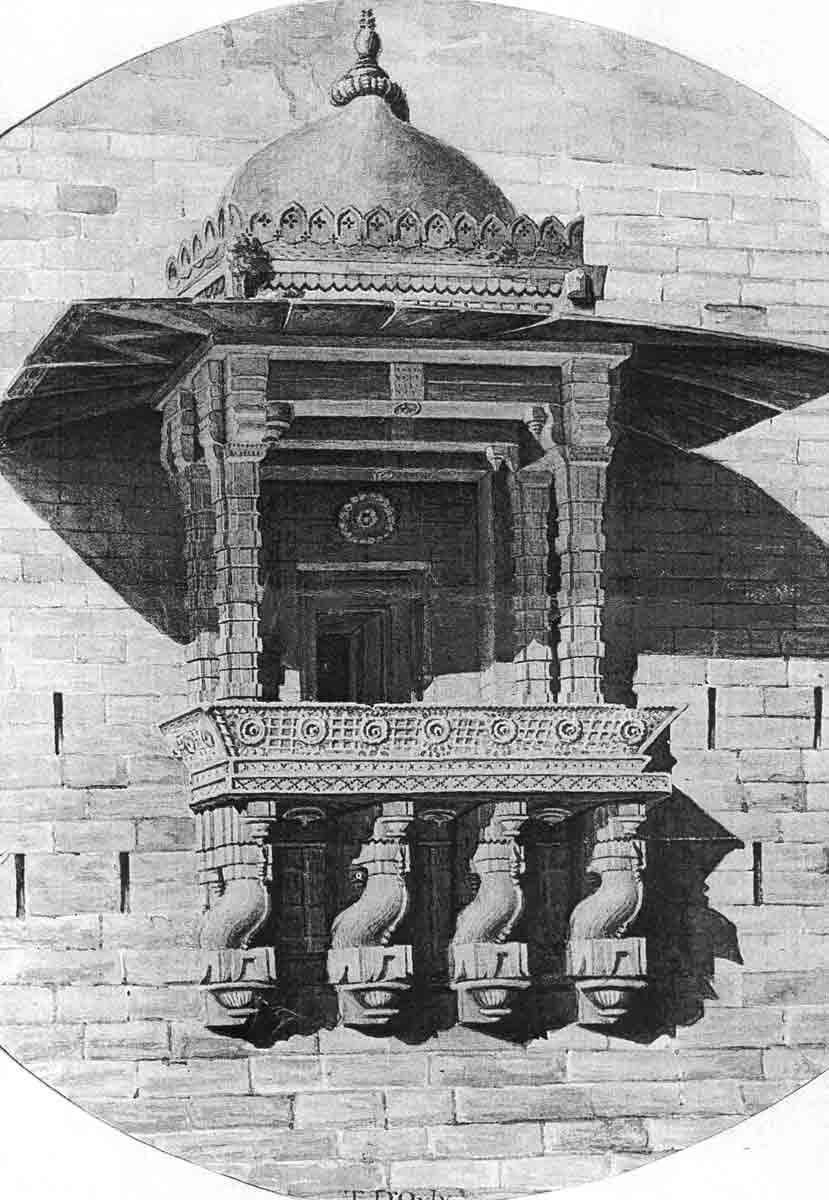

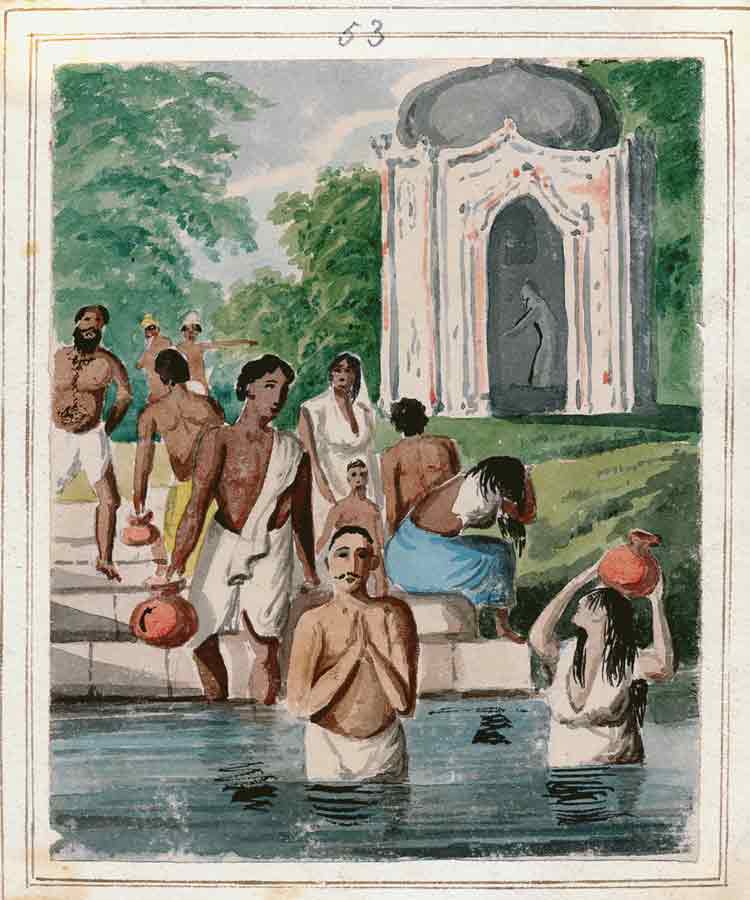

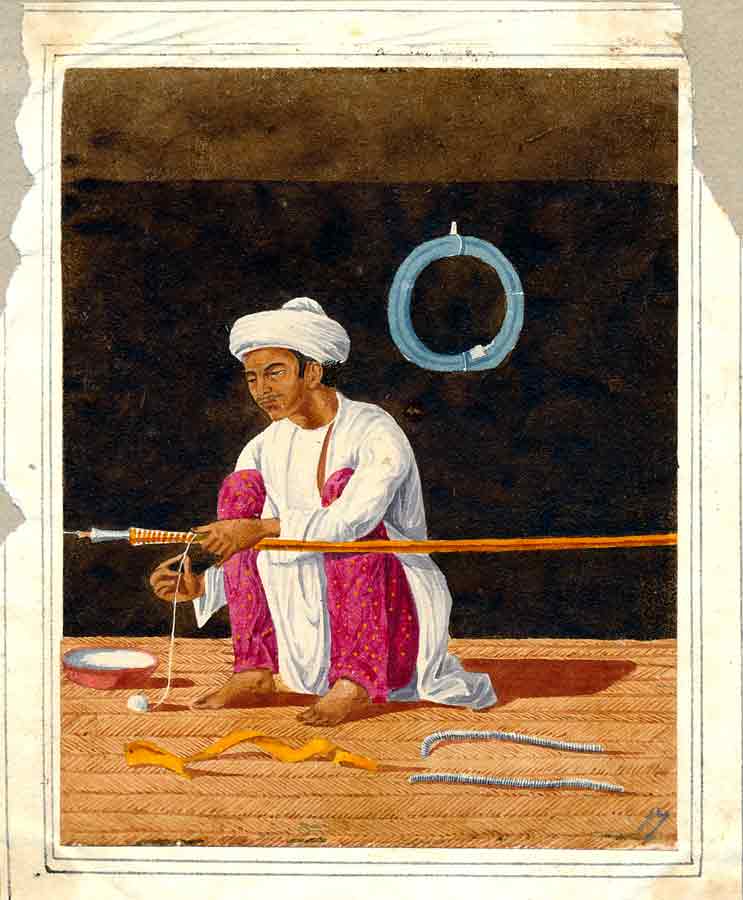

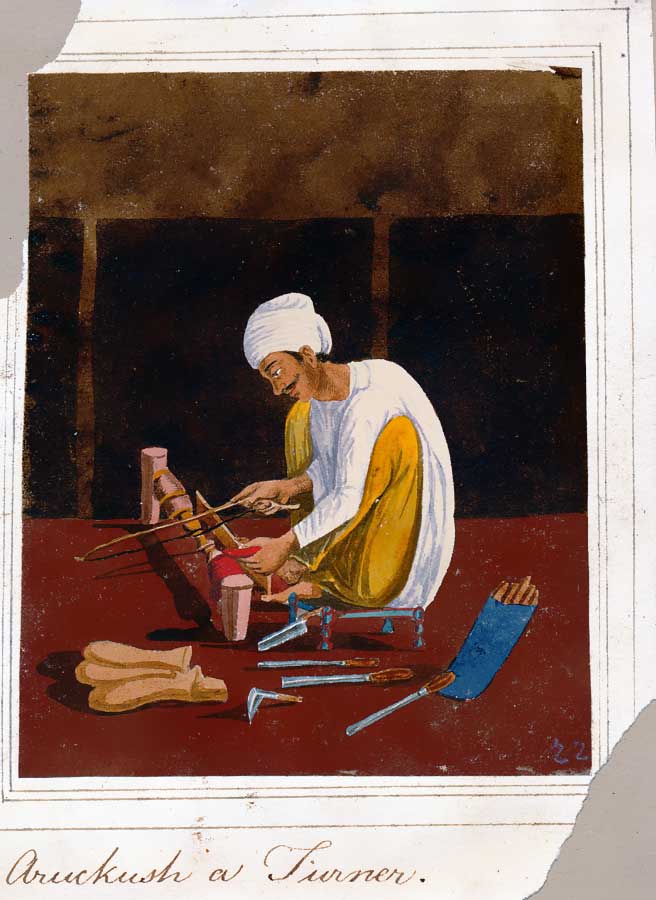

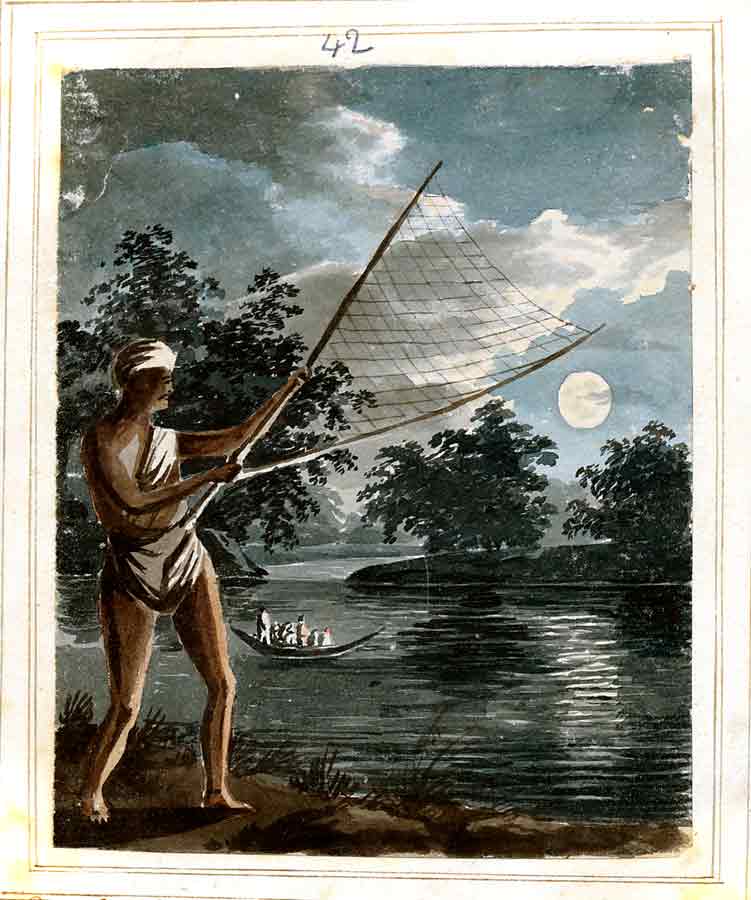

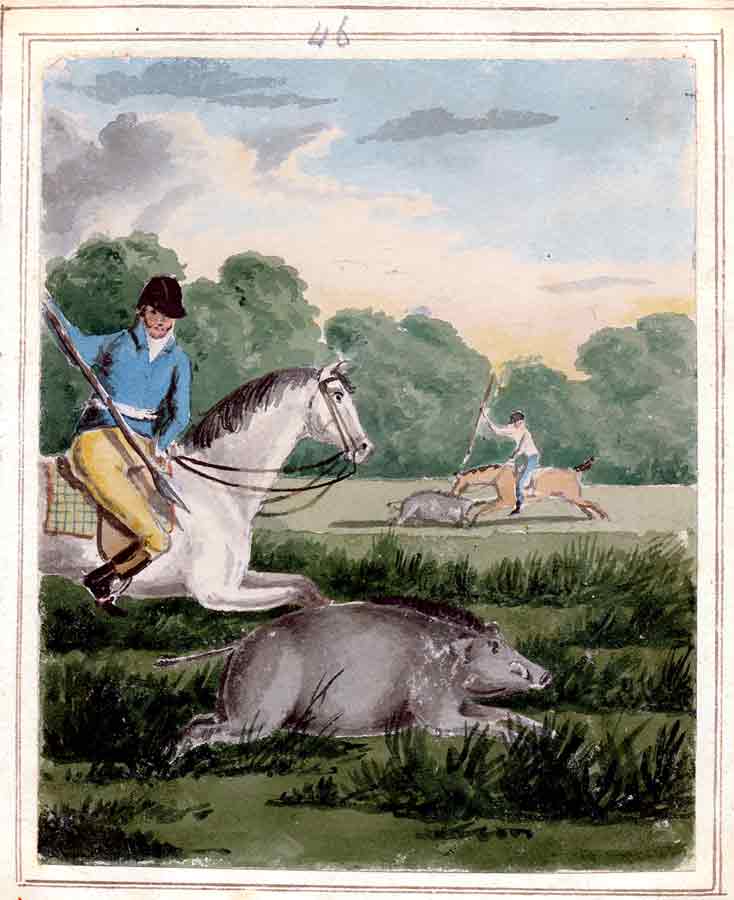

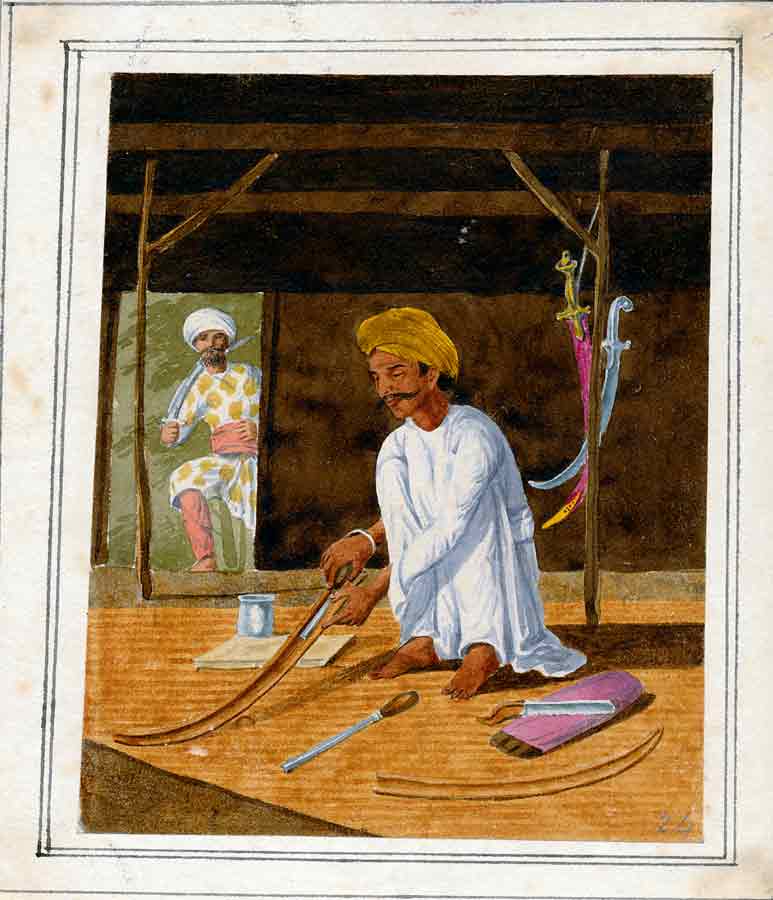

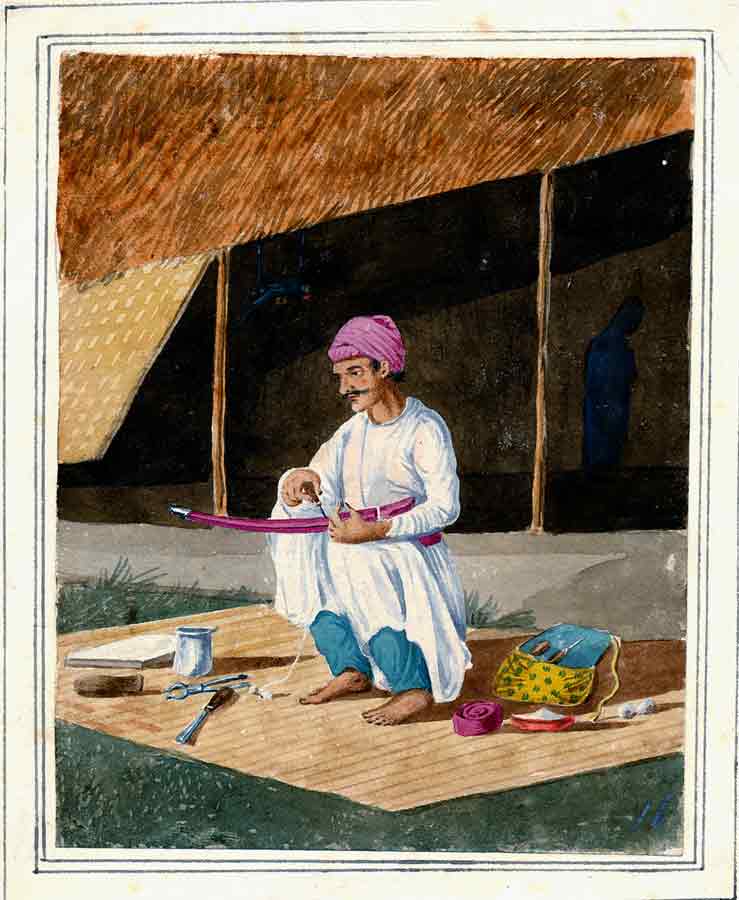

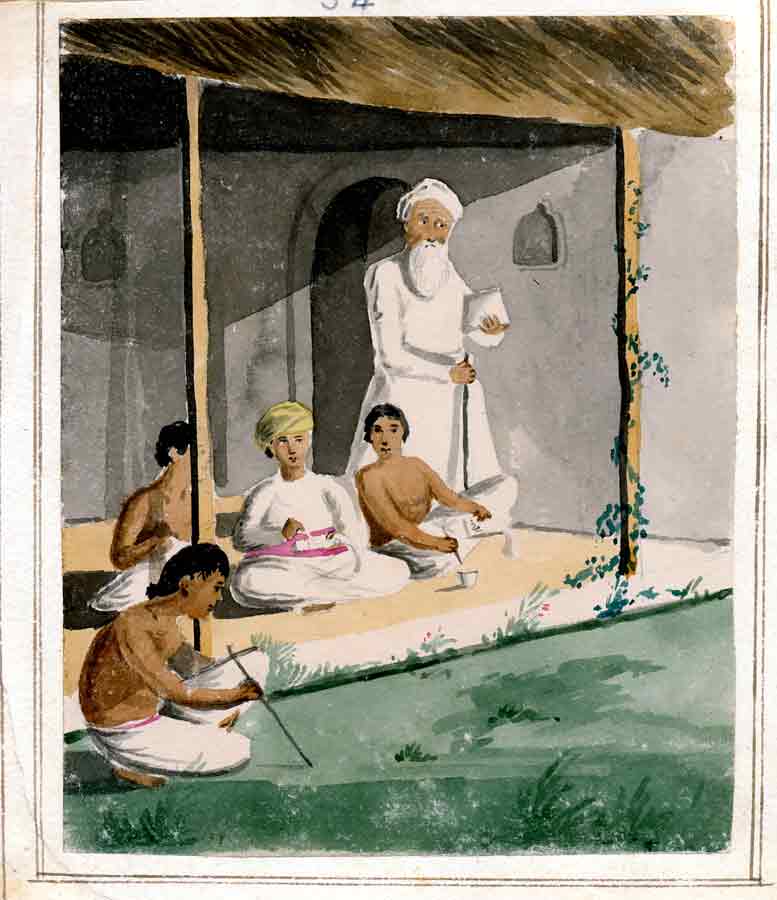

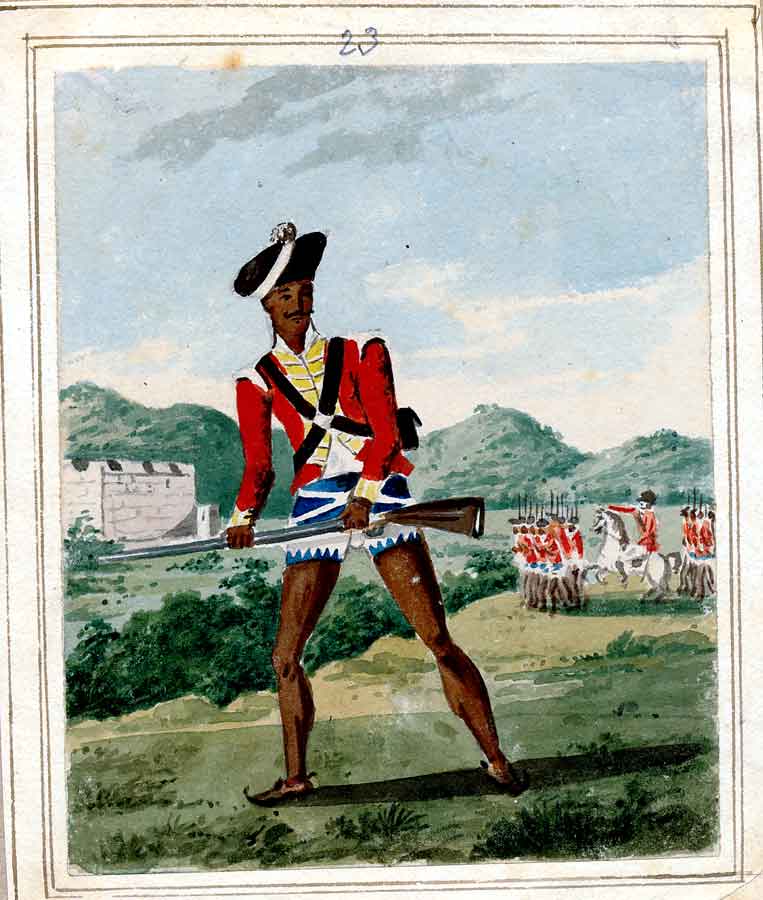

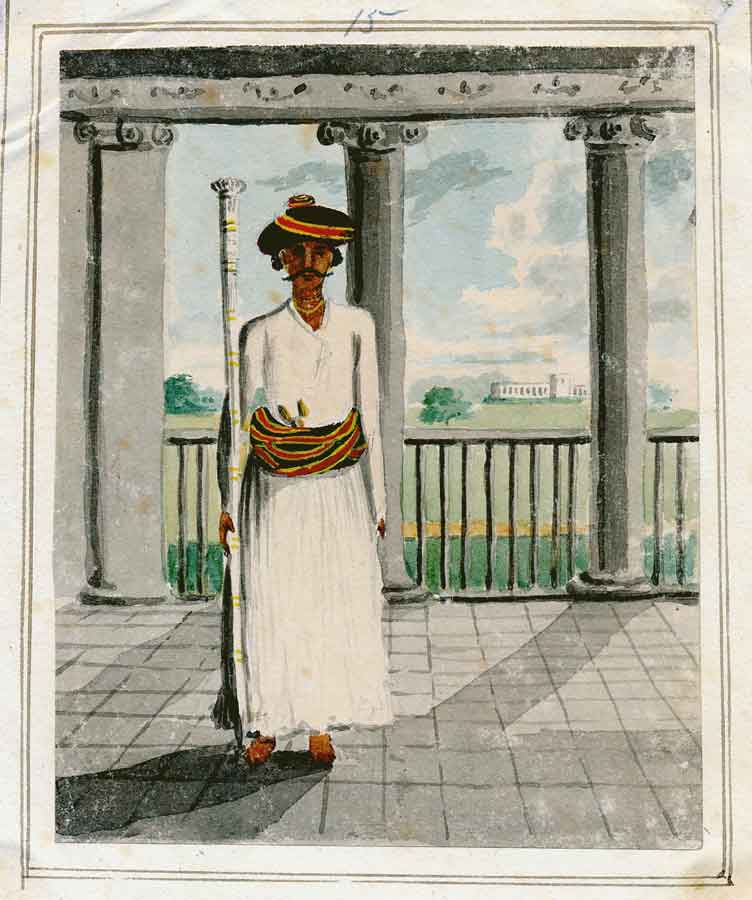

The lavish life of ‘eastern magnificence’ enjoyed by the D’Oylys in India has been part captured in these hastily executed little juvenile sketches. They have little or no value and are not well cared for, but they do reflect the lifestyles of the D’Oyly clan in Calcutta. The clothing dates the time-frame of the sketches to late-eighteen, early-nineteenth century. They are separate pages from a sketch book reportedly sold by Sotherby’s in 1992, and were attributed at the auction to ‘Sir John D’Oyle’, who never lived in India. He was on the Board of Directors for the East India Company for a time and would have had access perhaps to ex-colonists with India memorabilia. The sketchbook contained about 45 sketches, which were subsequently sold individually. They attempt to capture or recreate a bygone era with the simplicity of amateur photo snaps, and they are charming. I’m just grateful that someone bothered to take the time to paint them. They have been kept out of the sunlight and there appears to be very little fading. The better sketches are attributed to Sir Charles D’Oyly, the 7th baronet, and some of the cruder sketches perhaps to his younger brother, Sir John D’Oyly, the 8th baronet.

…

..

…

Notes to Chapter 3

- William D’Oyly Bayley, A Biographical, Genealogical and Heraldic Account of the House of D’Oyly, London: D’Oyly Bayley, 1845, p. 148. Much of the information in this chapter has been taken from D’Oyly Bayley, pp. 131−55.

- The ship’s largest shareholder was Charles Christie. D’Oyly, however, was a substantial part-owner.

- The North American Review, 1844, p. 342.

- The D’Oylys lost five children in a little over one year, including a stillborn daughter and another son who collapsed and died on his way home from school.

- William Bayley file, letter from Slade to D’Oyly family, 14 Nov. 1836, Dixon Library, State Library of New South Wales, A1074.

- Sion Hill was remortgaged in part to Mr William Bayley, of Northallerton. His son, also William Bayley, a solicitor in Stockton, married Edward and Hannah’s oldest daughter, Elizabeth. Private correspondence of Edward D’Oyly, in the possession of the author, dated 1815. The hall continued to exist for more than 100 years before being demolished for an architecturally superior new manor.

- For details on Captain Thomas D’Oyly, see Hodson, V. C. P., List of Officers of the Bengal Army, London, 1927–47, vol. ii, pp. 83–84; IGI; India Office Records L/MIL/10/23, ff. 171–72.

- East India Register and Directory, London: East India Office, 1818 and post.

- Edward Thornton, A Gazetteer of the Territories under the Government of the East India Company . . . 4 vols, London: W.M. H. Allen & Co., 1854, vol. 2 p. 10 and vol. 3 pp. 178–79. Also known then as Commercholly, Comercolly and more recently as Kumerkhali, it is now in Bangladesh, on the Ganges river north of Dhaka. Pubna is now called Pabna. Henry Williams was employed in the Company’s service from 1792–1833.

- See the will of Mrs Charlotte Williams, dated 1811, held by the National Archives UK. Mrs Agnes Williams, in a letter c. 1845, supplied the family genealogist, D’Oyly-Bayley, with their birth years. According to IGI the girls were born at the Williams ancestral home in Winterbourne Herringston, Dorset.

- The occupation as a writer/clerk in India was reserved for close relatives of EIC owners and directors. Mrs Williams (née Burrington) does not appear to have played a prominent role in her daughters’ lives. In those days, when a couple separated the father automatically under law had first claim to any children.

- Charles Hardy, revised by Horatio Charles Hardy, A Register of Ships, Employed in the service of the Honorable the United East India Company, from the Year 1760 to 1810 . . . , London: Black, Parry, and Kingsbury, 1811, p. 120.

- For information about Princess Mary, see Flora Fraser, Princesses: The Six Daughters of King George III, New York: Anchor, 2006.

- A comb thought to have belonged to Charlotte was later found on an island called Aureed.

- Ultimately inherited by their second son, Edward Armstrong Currie D’Oyly until his death in 1857. Source for location: Calcutta Gazette, July 1889.

- William D’Oyly Bayley, A Biographical, Historical, Genealogical, and Heraldic Account of the House of D’Oyly, London, 1845, pp. 131–55.

- Married 27 May 1819, at Northalleton, Yorkshire. Source: IGI. (William D’Oyly Bayley was their eldest son).

- Walter Hamilton, ‘Chunar’, East India Gazetteer 1825, London: W. H. Allen, 1828, p. 284.

- Right Rev. Reginald Heber D.D., Narrative of a Journey through the Upper Provinces of India from Calcutta to Bombay, 1824–1825 (with Notes upon Ceylon,) : An account of a journey to Madras and the Southern Provinces, 1826, and letters written in India, vol. 1. London: John Murray, 1843. Section on Chunar, Chapter XIII, pp. 401–13.

- D’Oyly-Bayley, p. 155.

- Losty, J. P., ‘A Princess’s Memento’, South-Asian Studies, no, 7, 1991, pp. 75–82.

- IGI.

- William Bayley file, Charlotte D’Oyly to Bayley, 20 July 1834, Dixon Library, State Library of New South Wales, A1074.

- Hobart Town Courier, 20 Sept. 1833.

- Hobart Town Courier, 12 July 1838.The newspaper advertisement, placed by Armstrong on behalf of the Calcutta lawyer tasked with finalising Captain Tom D’Oyly’s affairs, does suggest that the D’Oylys were checking out the colony with their forthcoming retirement in mind.

- For a description of the complaints suffered by India invalids, see James Johnson, M.D., An Essay on Morbid Sensibility of the Stomach and Bowels . . . to which are added, observations on the diseases and regimen of invalids, on their return from hot and unhealthy climates, 4th edn, London: Thomas & George Underwood, 1827, pp. 129–66.

- Initially posted to the ordnance at Allahabad in a senior position, but subsequently changed to an even more important role at the ordnance in Agra..

…

…

…

CHAPTER FOUR: TOWARDS THE ABYSS

The crews of British ships got a half-day off once a fortnight, always on a Sunday. When they were at anchor in a healthy port, one half stayed on board after the customary morning religious service and were assigned to light duties, while the other half spruced up in what passed for their Sunday best. Their usual practice was to extract as much of their due wages as their captains were prepared to give them, then head for the inns and taverns and blow the lot in one glorious binge that could often last for days. The Jane and Henry crew was on hand as fellow drinkers for the Charles Eaton crew, as also were the sailors from the Arab, a recent arrival with another load of 228 male prisoners. The assistant cook on board the Clyde was less fortunate. His body had just been found ‘dried up in the hold of the vessel, lying beside a spirit cask, having been some days missing.’1

Moore had trouble with his crew but so also did Captain Cobern of the Jane and Henry and John Harvey of the Red Rover. All three masters were called before the Hobart Town court, each on a different day, and fined five pounds with costs for ‘neglecting to keep sufficient watch’ on their ships.2

When the D’Oyly entourage – and Mr and Mrs Salting – joined the barque, dinners became a time for lively conversation. The D’Oylys and the Saltings shared a common interest in India. The Saltings were destined to become respectable pillars of Sydney’s society but in 1834, they were an adventurous young couple who had married just prior to booking their passages to Australia on the Meanwell. Severin was a 29-year-old Dutchman who had worked as a trader in India for 10 years. Back in London in 1833, he had married Louisa Fiellerup, whose Danish parents had also lived in India for a time.3 Although they were together only briefly, the two couples got on well and the Saltings would later describe Charlotte and Tom as ‘amiable’.

Louisa was probably pregnant before the Meanwell left London. Unwilling to linger in the Van Diemen’s Land colony while their captain advertised and sold his cargo of merino rams, the Saltings transferred across to the barque, due to depart almost immediately for New South Wales. Louisa would certainly have been grateful for the presence of other women, as she had no female companion of her own.

While the barque was still sailing up the Derwent River, she passed the Indiana, out of Calcutta and still under the command of Captain Webster.4 The ship was carrying more India invalids and would return directly to Calcutta. It must have been a poignant moment for the D’Oylys. Had they delayed their stay in the colony for a few days, they could have booked return passages aboard it. Instead, they were now committed to a slower route on a much smaller vessel and the possibility of tramping around many ports.

With his stiff military bearing, Tom must have cut quite a dashing figure on his strolls around the deck. He would later be described by his nephew, William D’Oyly Bayley, as ‘a sensible and upright man; prudent from his earliest childhood; a clever artist; a fine soldier; and of a tall fair handsome person’.5 Charlotte was a more robust memsahib and her special talent was the gentle but crushing reprimand. Their two son s, George and William, were especially appealing with their delicate complexions and flaxen hair. George was a very handsome and friendly boy but William attracted more attention, for he had the unusually broad countenance of a perpetual ‘babyface’, virtually guaranteeing that others would judge him as younger than his years.

If you had to embark on a long sea voyage with children in those days, taking an Indian ayah (children’s nurse) with you was one way to make it more bearable. Even the most fervent Anglophile had to admit that the Indian traditional sari was a much more practical garment for cabin life than the extraordinary gowns being worn by their European mistresses, with their wide skirts bloated with petticoats and their puffy sleeves. It is probable that Charlotte did know her servant’s name. Yet her identity remains unknown. She probably slept in the children’s cabin and took her meals there alone. Ayahs rarely occupied a vacant cabin berth and never dined at the captain’s table. John Ireland would later describe her as a ‘servant girl’6 so it is possible that she was quite young but not necessarily childless. Ayahs almost invariably began their working lives as wet nurses to English mistresses, for whom breastfeeding was an irksome and exhausting chore. They stayed on to perform more general duties, including brushing and braiding their memsahib’s hair. We can only guess at how well Charlotte treated her children’s ayah, given that her grandmother had performed a similar duty for Princess Amelia. Charlotte herself had been, apparently, a loyal and privileged lady servant to Princess Mary, the Duchess of Gloucester. Perhaps she followed royal example and treated her own ayah as a confidante and friend.

Below: Example of an ayah’s garments in 1834. Reimagined by Veronica Peek from research, with help from artificial intelligence.

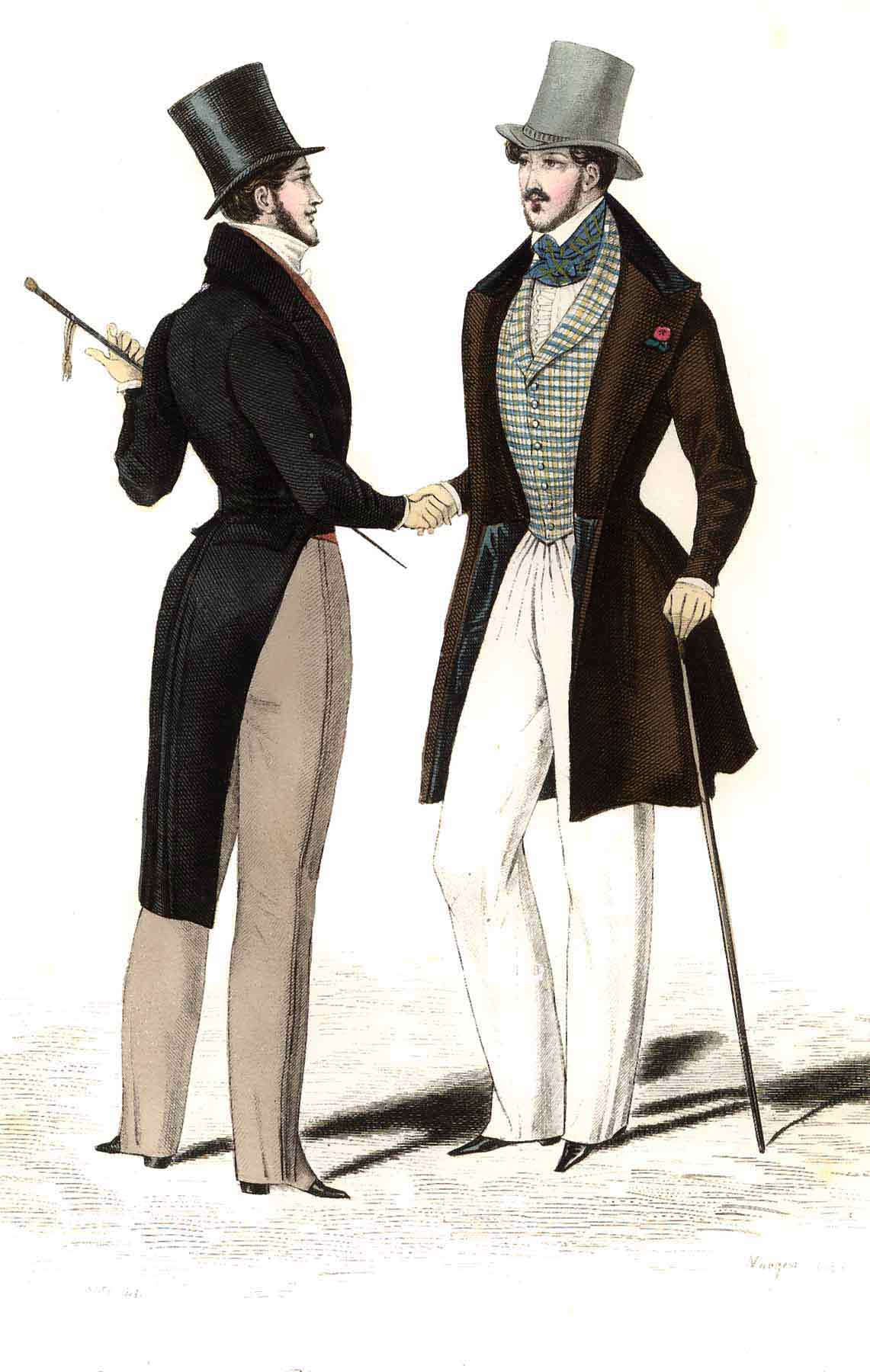

Men’s fashion 1834 from Costumes Parisiens, plate no. 3191, 15 July 1834 (below)

Three days after leaving Hobart Town, Tom D’Oyly celebrated his 40th birthday.7 Four days later the barque arrived in Sydney. The much smaller Jane and Henry was close behind. The Meanwell’s captain was still selling rams at Sullivan’s Cove.

By the time the Charles Eaton arrived at Sydney in July 1834, shipping trade with the Australian colonies was in a healthy state. Sponsored pauper passage had begun and would lead in time to an explosion in the number of emigrants. With the Swan River settlement recently established and two new colonies, at Port Phillip and South Australia, incubating into existence, it was a busy period in the country’s white colonisation. In addition, the Jane and Henry carried London newspapers containing the news that England’s convict hulks were being broken up. Over 8,000 prisoners (including the last 3,000 still left on the hulks) were about to proceed to Australia’s penal colonies.8

The wide harbour was remarkable on both sides for its many wooded coves and inlets but the pilot’s destination soon became obvious. To the west of Sydney Cove was a sandstone outcrop dotted with white cottages, to the east there were the Government House gardens, and to the south a number of tall warehouses. Behind the warehouses was a modern town. At anchor within the cove were a dozen or more merchant ships. Once the barque had a secure moorage, a military guard came on board and took up temporary residence in one of the cabins. His job was to prevent any cargo from being landed without proper clearance.9