Chapter 6: bad tidings about the Charles Eaton

by Veronica Peek

……...

On 27 August 1834, 29 days after leaving Sydney,1 the Jane and Henry was still bobbing along the outer route and had not yet passed through the Great Barrier Reef and into the inner passage. A fierce tropical storm on 22 August would also have slowed her progress. A faster vessel was bound to overtake her and the first one to appear over the horizon was the 412-ton ship Augustus Caesar, ex-Sydney 10 August, under the command of Captain William Wiseman.

Wiseman’s ship fell in with the Jane and Henry and the two vessels proceeded in company through one of the more southern entrances in the region of Sir Charles Hardy’s Island, and into the inner passage. For the next four or five days the two masters guided their ships through a maze of reefs near the tip of Cape York Peninsula, taking constant soundings and seeking safe night anchorage.

Wiseman was a seasoned master and well aware of the dangers of the route.2 In 1829 he had been master of the barque Lucy Davidson on the London–Sydney route, and in 1832, he had been in command of the convict transport ship Isabella. He had an experienced crew on this voyage and he approached the Torres Strait with caution. On 31 August, the two vessels rounded the corner into Torres Strait and at 3 o’clock in the afternoon, the Augustus Caesar anchored on the lee side of Nalgi.

Nalgi, also known then as Double Island but now called Twin Island, is in the centre of the main passage through the Torres Strait and about 20 nautical miles north of the tip of Cape York. Having anchored for the night, Wiseman allowed his second mate, Hartley, to go ashore with two of his men. They were shocked to discover that a beach on the southeastern side of the island was strewn with ship’s wreckage. Spread out along the sand was a quantity of light driftwood, including cuddy doors and windows and two planks from the side of a ship. Hartley and his men set off and walked around the island but could find no trace of the main wreck, or any of the passengers or crew. After three hours, they returned to their ship to report their find. According to Wiseman:

They brought with them a window frame, a keg and other fragments of wreck, sufficient to convince me it was the Charles Eaton, and that she must be at a considerable distance to windward of Double Island, probably near Mount Adolphus, Cape York, or the reefs or Islands in their vicinity, they being directly to Windward.”3

The window was probably from one of the barque’s stern cabins. There were also several brass locks with her name upon them that must have been attached to the wreckage of doors or windows, while one of the kegs had the name CHARLES EATON written on it. The Augustus Caesar and the Charles Eaton were moored together at the St Katharine’s dock for many weeks and Wiseman was familiar with the barque’s appearance. He was in no doubt that the wreckage had come from her.

The crew of the Augustus Caesar then spent what must have been a nervous night anchored off Nalgi. The saw a number of fires on nearby Maururra (Wednesday Island) that might have been lit by survivors from the shipwreck, yet no one considered it safe to investigate. For whatever reason, Wiseman also failed to tell Captain Cobern and the crew of the Jane and Henry about the wreckage. The following morning the two vessels proceeded through the strait and anchored at Booby Island.

Booby Island is a rock near the main shipping route through the Torres Strait, regularly visited in those days by the crews of European ships. They were giving themselves, as Captain Stokes RN later wrote on his visit there, ‘a short period of repose and relaxation after the anxieties and danger of the outer passage’.4 The rock is invaded every year by colonies of nesting boobies. Its most noticeable feature is the bird droppings that cover its summit, hence the name given to it independently by both Captain William Bligh and Captain James Cook. It was also the first stop for any survivors shipwrecked on the Barrier Reef. Wiseman sent officers and some of his crew ashore but they found no trace of any castaways. Cobern now learned for the first time of the fate of his former companion vessel and that Wiseman’s men had found a cuddy door and a cask labelled Charles Eaton. He was unaware that the debris was at Nalgi, and assumed it was on Booby Island.

The Jane and Henry continued on to Batavia (now Jakarta) and remained there for six weeks before returning to Cape Town. The news of the Charles Eaton’s fate was contained in a letter from Messrs Borradaile and Co. of the Cape of Good Hope, addressed to Messrs Gledstanes.5 It was received in London on 26 February 1835. It gave the owners the terrible news about the loss of their vessel but implied that sailors had found wreckage from it at Booby Island. Not long after, Lloyd’s of London posted Wiseman’s accurate account, with the observation that: ‘from the weather they had on the 22nd [Aug.] they much feared for the safety of the crew and passengers.’6

It was the Irish Protestant newspaper, the Freeman’s Journal, however, that was among the first to publish the news of the shipwreck, with details reportedly from a ship’s passenger recently returned to Dublin from the southern seas. In its 14 Feb. 1835 issue the journal reproduced the following news item:

BARQUE CHARLES EATON.–We regret to hear that a letter is in town from a passenger in a ship just arrived, in which it is mentioned that some Cabin stores of the Barque Charles Eaton, from Sydney to Singapore and Calcutta, have been picked up somewhere near Torres’s Straights [sic]; whence the loss of that vessel is inferred. She sailed from Sydney on the 29th of July, and therefore was greatly out of time. The following is a list of the passengers given in the Sydney papers; –C. G. Armstrong, Esq; Captain and Mrs. D’Oyly, W. and E. D’Oyly, and a native servant.

The journal’s editor was unaware that Armstrong had relatives and friends in Ireland who knew of his overseas movements, probably from letters posted by him en route. The news had come completely out of the blue and they were understandably shocked. One of them even demanded a retraction of the shipwreck claim. The Freemason’s Journal obliged in their next edition (17 Feb. 1835):

We copied from the Courier into our number on Saturday, a paragraph relating to the Bark Charles Eaton calculated to give distress to the minds of some connections of those on board, for which we believe there is no foundation. The Charles Eaton left Sydney we learn intending to proceed to Sourabaya and China – for the last place Mr. Armstrong was a passenger. His not arriving at Singapore therefore, is accounted for by the fact of her not having been destined to go there at all. The cabin stores said to have been picked up “somewhere near Torres’ Straits” by what vessel is not stated, consist we are informed of the lid of a chest, which of course may have been thrown overboard. The vessel may not have been able to fetch Sourabaya and have gone round to the northward of New Guinea. She might not therefore have reached China at the date of our last intelligence, but there is no particular reason for alarm about her. The passengers who embarked for Calcutta would of course have to wait at Sourabaya for an opportunity for Singapore.—

Armstrong’s agitated connections were in denial and their hopes were soon dashed when the official notice of the shipwreck was posted at Lloyd’s of London. Included among those connections were the Armstrongs of Banagher in King’s County, a few of whom were among the wealthiest land-owners in Ireland. During his Sydney stopover, the young barrister (or a creditor perhaps) had addressed a letter to Thomas H. (St.) G. Armstrong at Banagher. It was later listed in the Sydney Herald (10 Nov. 1834) as still at the post office because its paid postage was insufficient.

News of the shipwreck had already reached India by this time, possibly via the Jane and Henry. At about the same time that the barque had disappeared, the East India Company (EIC) changed Captain D’Oyly’s recent promotion to the Agra station to a similar position at the Delhi magazine and the company expected him back in Calcutta by December or January 1835 at the latest. When many months passed and the D’Oylys failed to show up, their Calcutta relatives endured a ‘painful interval of suspense’7 during which ‘the most gloomy surmises were entertained as to the possible fate of the captain and his family’.8 Their fears were confirmed by the arrival of Sydney newspapers dating from July 1834, which contained the barque’s passenger list.

For a time the only other news of the barque’s fate came to the D’Oyly relatives via rumours. The crews of passing ships had sighted the Charles Eaton wreck, firmly wedged on the Great Detached Reef and reasonably intact. It meant that there would have been time for survivors to leave the wreck in boats. Later, stories began to circulate throughout the main trading ports of South-East Asia that some of her crew were captives on an island. They were probably spread by the crews of Dutch trading praus recently returned from Timor. They were certainly both widespread and persistent, though not reliable enough to encourage anyone to do anything about them. In the Dutch East Indies, meanwhile, other events connected with the Charles Eaton were already unfolding.

….

NOTES TO CHAPTER 6

- Twenty-nine days does seem like unusually slow progress. On her subsequent voyage the Jane and Henry covered the distance in 20 days. The Charles Eaton reached Sir Charles Hardy Island in 17 days, as also did the Augustus Caesar. We don’t know for certain why the two ships parted company and to be fair to Captain Moore, it’s possible that the Jane and Henry had to make a scheduled or unscheduled visit to a seaport. You can also argue that it would have been impractical for Moore to slow down his barque to match the smaller schooner’s speed.

- Mr Wiseman to Mr Nicholson, Master Attendant, letter dated 1 April 1836. Historical Records of Australia, vol. XVIII, 1836, pp. 432–34, enclosure.

- The Times, 23 Sept. 1836. Hartley and Wiseman also inspected some bones near the remains of a fire. They are unlikely to have been human and are more likely to have been canine or marine, e.g. the remains of a dugong. Despite this, many people did believe that the bones found by Hartley and Wiseman were the remains of some of the crew and passengers and that their discovery was further proof that the unfortunate castaways had been wholly cooked and eaten.

- J. Lort Stokes, Discoveries in Australia . . . , vol. 1, Australiana Facsimile Editions no. 33, Adelaide Library Board of South Australia, 1969. The Booby is a gannet, so named because it trusts enough to be considered stupid, and thus is easily caught and killed by hungry sailors.

- William Bayley file, copy of Borradaile letter, Gledstanes to Bayley, Dixson Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, A1074.

- Allan McInnes, ‘The Wreck of the Charles Eaton’, read to a meeting of the Royal Historical Soc. of Qld, 24 February 1983, p. 22.

- Thomas Wemyss, Narrative of the Melancholy Shipwreck of the Ship Charles Eaton . . . , 2nd ed., Stockton-on-Tees: J. Sharp, 1884, p. 12.

- Wemyss 1884, p. 12.

Chapter 7: the Tanimbar connection

About 220 miles (350 km) north of Australia is a group of islands collectively called Tanimbar. They are Australia’s nearest neighbours in the Arafura Sea.1 There is a channel south of the largest island of Yamdena that separates it from the smaller island of Selaru, while to the north of Yamdena there are two more islands called Fordate (more recently Vordate) and Larat. These islands were almost unheard of in Australia in the nineteenth century — and that is still the case today.

Although the islands of Tanimbar are part of the Moluccas, the Dutch administration at Amboyna had no official contact with their inhabitants until 1646. At that time, the islands’ leaders gave the United East India Company of the Netherlands sole trading rights to the trepang (sea slugs) caught off their surrounding reefs.2 Although the trepang had little value to the islanders, they were a much-fancied delicacy on the Chinese market. The Dutch built a fort on Fordate, to protect their exclusive trade. They also posted a missionary there and later a schoolteacher. Their goal was to convert the islanders to Christianity.

Trading vessels were showing signs, even then, of being reluctant to have much contact with the Yamdenans, so it was good news for their captains when the Dutch residents and soldiers started promoting the town of Sebeano, on the western coast of Fordate, as christianised and a protected trading post. For a time the remote little post flourished, and many trading praus called there. The Fordate islanders were hospitable but most European mariners still preferred to avoid the region. Murderous pirates infested the Timor and Arafura Seas.

Sebeano eventually became so popular with visiting trading praus from the islands of Banda, Macassar and Garem that they undermined the Dutch trade monopoly over the Tanimbar Islands. By the middle of the 18th century, the Dutch had concluded that trade at Tanimbar was too unprofitable to warrant the cost of maintaining a presence in the islands.3 They withdrew from Sebeano and had no further contact with the Tanimbar islanders until 1825, when a Dutch brig-of-war under the command of Lieutenant D. H. Kolff sailed through the outer reaches of their trading empire. He reminded everyone that all trade was still under Dutch control and appointed representatives called Oran Kayas to protect Dutch trading interests.4

Lieut. Augustus L. Kuper, a navy officer temporarily serving with Lieut. Owen Stanley, commander of the British navy’s brig H.M. brig Britomart, which called there in March 1839, provided the first published account of an English vessel’s visit to the much-feared and avoided island of Yamdena. On making landfall near Oliliet (now Olilit) village, the men aboard the brig observed two large praus flying Dutch colours coming out to greet them. Describing the meeting that followed, Kuper wrote:

At 9, we observed two large canoes under sail, standing out from the land towards us – they shortened sail several times as if in doubt what to do, but about noon they came alongside, and several natives came on board. They came from the village of Oleillet [sic], off which they gave us to understand there was a good anchorage, and as it was the nearest place we could reach we stood in for it, taking their canoes in tow. An elderly man, apparently the head man of the party (man’s name – Gamble or Grindall), handed us a small flat basket containing several old leaves from an old remark-book, written in pencil, a torn leaf of a navigation book, and two small pieces of black lead pencil. . . . As I could not prevail on him to part with them in exchange for anything I had to offer, I took a copy of as much of it as I could decipher, although the contents were of little value. 5

The old man was one of the chiefs of Oliliet village. He kept repeating the name ‘Grindall’ and the Britomart officers assumed he was identifying himself. Only later did they realise that his name was actually Lomba. He was a ‘little thin shrivelled old man’6 dressed in a long black serge coat and a blue striped or checked shirt, which he pointedly displayed to the navy officers. The name ‘T. P. Ching’7 was marked upon it and the materials he presented to Lieut. Kuper in a neat little basket were crude relics of the Charles Eaton story.

Five years earlier, on about 1 September 1834, Oliliet’s peaceful day had been interrupted by the arrival of a large ship’s cutter containing five sailors. They had been at sea and under sail in the open boat for 15 days and their provisions were almost gone.8 On landing at the beach below the village, they went ashore and helped themselves to fresh water and coconuts, before returning to their cutter and continuing down the coast. The villagers, however, had noticed their presence and they followed the cutter and surrounded it with canoes. Too exhausted to resist and having no weapons, the five men surrendered to the islanders.

Their boat was upset and they were stripped of their clothes, then taken naked and quaking back to Oliliet beach, where the violent gestures of the villagers let the sailors to believe they were about to be killed. Fortunately two old chiefs, Pabok and Lomba, intervened to spare their lives. To prove they meant no harm, these two leaders made sure the sailors got back most of their clothes. The five sailors were lucky to be alive. They had stolen tradable resources from the beach and it was not the practice of the Yamdenans (who were themselves great pirates) to spare the lives of other thieves.

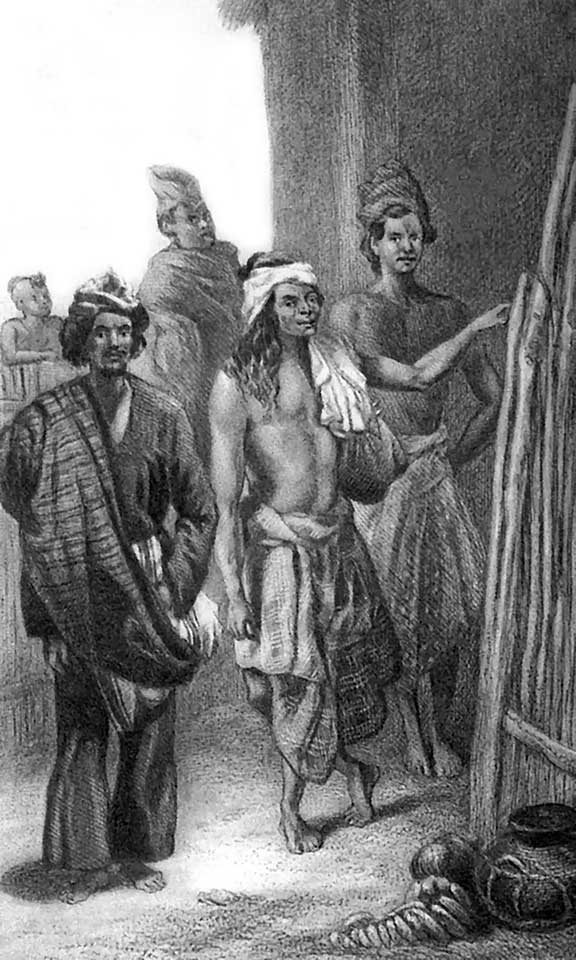

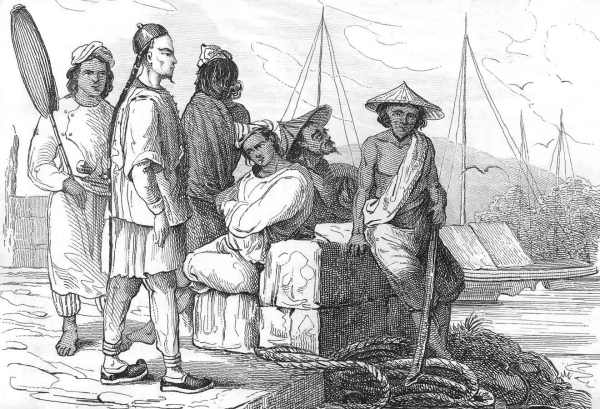

The five sailors in the ship’s cutter were the carpenter Laurence Constantine, the boatswain George Piggott, and three seamen − Richard Quin, William Grindall and James Wright. The men who now surrounded them were mostly healthy and athletic, with handsome features. Although by no means completely isolated from the Indonesian archipelago, there were aspects of their appearance that suggested their culture had developed its own hybrid qualities.

Their single garment was a very short sarong, sometimes adorned with shells. Enormous solid earrings, roughly shaped like padlocks and almost touching their shoulders, had extended the holes in their ear lobes. They fashioned attractive turbans from their own black hair, by cutting it to a length of about 10 centimetres, bleaching it fair with lime paste, then growing it very long so that it was two-toned. They then coiled their hair around their heads in a variety of fancy and fantastic shapes and fastened it with large wooden combs.9

Oliliet village was directly above the beach and hidden from view by thick vegetation. To reach it, the villagers escorted the five men up a long, steep flight of steps, cut into the side of the hill. That was the easy part. To reach the summit it then became necessary to climb two wooden ladders, placed almost perpendicularly against the cliff face and clearly intended for defence. Their removal would make it impossible for anyone to attack the village from the seaward side.

From the top of the cliff, the sailors had a panoramic view of the sandy bay they had just left behind. All along the beach were coconut plantations, interspersed with thatched boat sheds housing outrigger canoes. Within the bay were several small, rocky islands. Constantine and his companions could hardly have failed to notice them as they were passing by in their cutter, since on at least one of them there were several decomposing bodies, packed into shells or woven grass boxes. That island was Oliliet’s current graveyard and a useful way to keep the stench of decay at bay. For anyone passing by in a boat, however, the odour from the island was awful.

The village had more than 150 houses and a population of about 1000. Entrance to it was along a single narrow path to a gate, guarded by a timber fort flying the Dutch ensign and manned by soldiers armed with bows and arrows. There was one long and wide main street and two parallel secondary streets and the whole village was enclosed on the jungle side behind a wall. All of the houses faced towards the main street and sat on stilts. Their most striking feature was their tall, steeply pitched thatched roofs. The peak of each gable had large wooden carvings shaped like stylised buffalo horns, from which strings of twine tastefully decorated with shells hung almost to the ground. The overall effect was very picturesque.10

The five sailors soon discovered that the interior of each house was a single room divided by a wooden alter panel dedicated to Oliliet’s god, with arms raised to convey the impression it was supporting the roof beam. Most of these panels were finely carved and exceptionally beautiful, while the roof beam was the place where the occupants stored the heads of ancestors – but not those collected as spoils of war. The Tanimbar islanders were headhunters but after the heads of enemies had served their purpose as ritual offerings, the men tossed them over the wall and into the jungle.

The women and girls were uniformly dressed in dark wraps reaching to their knees or ankles. They, too, wore very large earrings but they were lightweight gems of lace-like filigree, often made from metal, while their numerous arm and ankle bands were fine circles of polished conus shells. Like their male counterparts, the younger women were strikingly attractive.

The Dutch-appointed Oran Kaya had his house near the centre of the main street. Adjacent was a circle, marked out by a low stone wall. When decisions had to be made that affected the whole village, as had now occurred with the arrival of five shipwrecked sailors, everyone assembled there, forming a large circle around the perimeter of the wall. Although it may not have looked like it, the stone circle represented a boat. The bow of the boat faced towards the sea and contained a wooden post and the sacrificial alter. The most valued offering to their god was a human head. At the stern of the boat was a woven wicker bench for the senior ritual officials, the mela snoba in charge of sacrifices and offerings and the meta fwaak, or herald, who walked through the village crying out all decisions.11 As far as the five sailors could see, Pabok and Lomba were chiefs. It is possible they were the heads of Oliliet’s two main clans. Lomba’s black serge coat was a common badge of authority around the islands but he certainly was not the Oran Kaya, although that man also proved to be quite elderly and courteous.

The villagers finally sanctioned saving the sailors’ lives. Lomba gave the five men his personal protection and if trouble erupted, he would intervene on their behalf. As a token of gratitude, they gave him Ching’s shirt, which one of them must have been wearing at the time they abandoned the barque. The sailors would later say that the Yamdenans never treated them as slaves or forced them to work – but they were prisoners, with no freedom to leave unless granted by the chiefs.

Women tended crops and livestock, fished on the reefs, cooked the meals and raised the children. The men burnt off gardens, fermented the popular and potent palm wine, went on long trading voyages, built canoes, fished for trepang and continued their war with the nearby village of Lauren. Slaves had no status and had to do all kinds of menial chores.

Exactly what triggered the war between Oliliet and Lauren was buried under layers of payback. In any event, if Oliliet had been on good terms with Lauren, it would have been doing battle with another village. The Yamdenans were militant and easily offended, and they made inter-village agreements for mutual support that dragged them into a mesh of disputes.

Although the Oliliet villagers used Javanese as the language of trade when dealing with the crews of visiting Dutch praus, at all other times they spoke their own language. The five shipwreck survivors needed to pick up the rudiments of it quickly, and this they apparently did with enough success to procure their survival. After a time they learned that another European sailor was also being held captive – at Lauren. According to the Oliliet villagers, a brig had wrecked off Lauren village some years ago and all the crew murdered except two boys, one of whom had since died.

Thirteen months after their arrival, a Dutch-owned trading prau en route to Amboyna (Ambon) called at Oliliet. It was an unusual event. No amount of tempting offers of iron axes or calico could induce the villagers to give up their livestock or vegetables. The five sailors immediately sought permission from Lomba and Pabok to leave with the Dutch prau. They got their freedom when they promised to come back in an English ship with arms, gunpowder and ammunition, so that Pabok and Lomba could defeat their enemies at Lauren. This was the gamble that Lomba was taking. He wanted and expected that there would be a generous reward as the sailors had promised. William Grindall gave Lomba a few items off the Charles Eaton that the old chief must have assumed was a contract, reference or proof of identity.

Before leaving the island, the prau visited Lauren village and the five men tried to get permission for the other shipwrecked sailor to come with them. His name was Joe Forbes and he had been a ship’s boy aboard an English schooner called the Stedcombe. It had been attacked and sunk off Lauret in 1824 and all the crew killed save Forbes and another ship’s boy who had since died. Forbes was a frail figure who had almost forgotten his native tongue, with the result that the sailors were unaware that he was English. He understood enough of what they were discussing, however, and was devastated when his own Oran Kaya refused to let him go. Although taken as a 14-year-old ship’s boy and now about 24 years old, he was so small and delicate that he looked much younger. He had been exposed to strong sunlight for a long time yet his skin was very pale. His hair had never been cut during his time on the island and it now reached almost to his knees, although he wore it in the local style, twisting it gracefully around his head like a turban and securing it with combs. It had been bleached with lime and was the colour of raw silk.12 The sympathetic feelings of those who met him were most aroused by his expression. He looked at the world with eyes that were always sad. He was about 5’2″ (157 cm) tall but his legs were bent and crippled from having been bound too tightly and too often, to prevent him from escaping.

Forbes had witnessed many cruel deeds. On one occasion, the Lauren pirates had boarded a Chinese junk, plundering it and murdering the crew before burning it down to the water. On another occasion, they had attacked a schooner. He had played a part in other acts of piracy and had his share of the spoils. He had a box filled with clothes and money — dollars, half-crowns, sixpences; these alone were his treasured possessions.13 The Charles Eaton sailors would later claim that Forbes had ‘reconciled himself to the manners and customs of the natives.’14 He was useful and a great favourite with the villagers, they said. So dismissive were they of Forbes that the English-speaking world forgot all about him until his rescue five years later, in 1839. His rescuer was Captain Thomas Watson of the schooner Essington, a vessel formerly better known as the colonial schooner Isabella.

Images of Tanimbar islanders from the early 20th century

Except where stated, all images of early 20th-century Tanimbar have been sourced from COLLECTIE TROPENMUSEUM Expeditieleden op de Tanimbar eilanden via Wikimedia Commons. Their collection seems to be unique for that period.

Notes to Chapter 7

- The name ‘Timor Laut’ (An ancient Malay name meaning Timor East or eastern sea) is no longer used for the islands of Yamdena/Jamdena and Selaru. Indonesians still refer to the Tanimbar or Tenimbar islands.

- See Susan McKinnon, From a Shattered Sun: Hierarchy, Gender and Alliance in the Tanimbar Islands, USA: University of Wisconsin Press, 1991, pp. 3–9 for more detailed information about Yamdena’s history.

- McKinnon 1991, pp. 3–9.

- D. H. Kolff, Voyages of the Dutch Brig of War Dourga, through the Southern and Little Known Part of the Moluccan Archipelago, and along the Previously Unknown Southern Coast of New Guinea . . . , trans. from the Dutch by George Windsor Earl, London: J. Madden & Co., [c.1837].

- Owen Stanley in J. Lort Stokes, Discoveries in Australia; with an Account of the Coast and Rivers Explored and Surveyed during the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle, in the years 1837–38–39–40–41–42–43, vol. 1, Australiana Facsimile Editions no. 33, Adelaide: Library Board of S.A., 1969, pp. 439–40. First published 1846. At the time of the visit to Timor Laut, Augustus Kuper, First Lieut. aboard the HMS Alligator, served as temporary First Lieut. to Owen Stanley on the brig H.M. brig Britomart. Kuper was the son-in-law of Sir Gordon Bremer, at that time the commandant and founder of the British station at Port Essington. Owen Stanley, who was often not a well man, concentrated on taking soundings and later prepared excellent charts of the voyage. Both officers kept journals. See Augustus L. Kuper, Sydney Herald, 22 July 1839.

- Kuper 1839.

- A shirt that once belonged to the young midshipman, Tom Ching, and possibly borrowed or stolen.

- See the sailors’ Batavia deposition, William Bayley File, Dixson Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, A1074, for details of their time at Yamdena.

- Stanley pp. 456–57; Kuper, Sydney Herald 22 July 1839.

- Kuper 1839.

- See McKinnon 1991, pp. 68–75 for a description of the rituals surrounding the ‘boat’.

- For a full description of the rescue of Joseph Forbes in 1839, see the logbook of Captain Thomas Watson on file at the National library of Australia; for a shorter version, see Captain Watson’s report to Commodore Sir Gordon Bremer, in Geoffrey C. Ingleton, True Patriots All, or News from Early Australia as Told in a Collection of Broadsides . . . , Rutland, Vermont and Tokyo, Japan: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1988. Reprinted Sydney: Angus & Robertson, pp. 204–07. However, I do recommend that you read Watson’s logbook. It is available online.

- Sydney Herald, 20 July 1839.

- Batavia deposition, William Bayley file.

……

……….

Chapter 8: Amboyna and Batavia

The Dutch prau carrying the five shipwrecked sailors arrived at Amboyna (Ambon) six days later, on 7 October 1835. As they sailed into the deep harbor, they would have seen many clove-tree plantations, mixed in with the natural mountain growth. The Dutch administrative centre of the Moluccas (Mulukas) on Amboyna still exported spices in large quantities, but the Dutch were paying more attention now to trepang, the Chinese delicacy easily caught around the islands. What had happened to the Moluccas had been tragic. Within a century of the arrival of European merchants, senseless over-production undermined a spice trade that had flourished for perhaps 1500 years.1

The sailors remained at Amboyna for two months. If they had to cool their heels in some distant port, there were a lot worse places than Amboyna. The Portuguese had selected it for their base in the Moluccas before the Dutch drove them out and it was the healthiest of the many trading centres in South-East Asia. The Dutch were on good terms with the British and gave the sailors a kind reception. The men said later that Captain Clunies of the Dutch brig Patriot took care of them.2

Meanwhile, the Governor-General of India, Lord Bentinck, responding to an appeal from friends and relatives of the D’Oylys, sent a dispatch to Jean-Chretian Baud, the Governor-General of Batavia. Bentinck asked Baud to ‘exert his influence in furthering the discovery of certain persons, passengers and crew of the ship Charles Eaton, supposed to have survived the wreck of that vessel in Torres Straits’.3 The dispatch arrived in Batavia on 20 November 1835, prompting Baud to send a vessel to Tanimbar and its neightbours. Rumours about the presence of white men on Yamdena must have been circulating around the Moluccas for months. Baud was not to know that the five sailors had already been rescued and taken to Amboyna, on the fringe of his homeland’s far-flung empire.

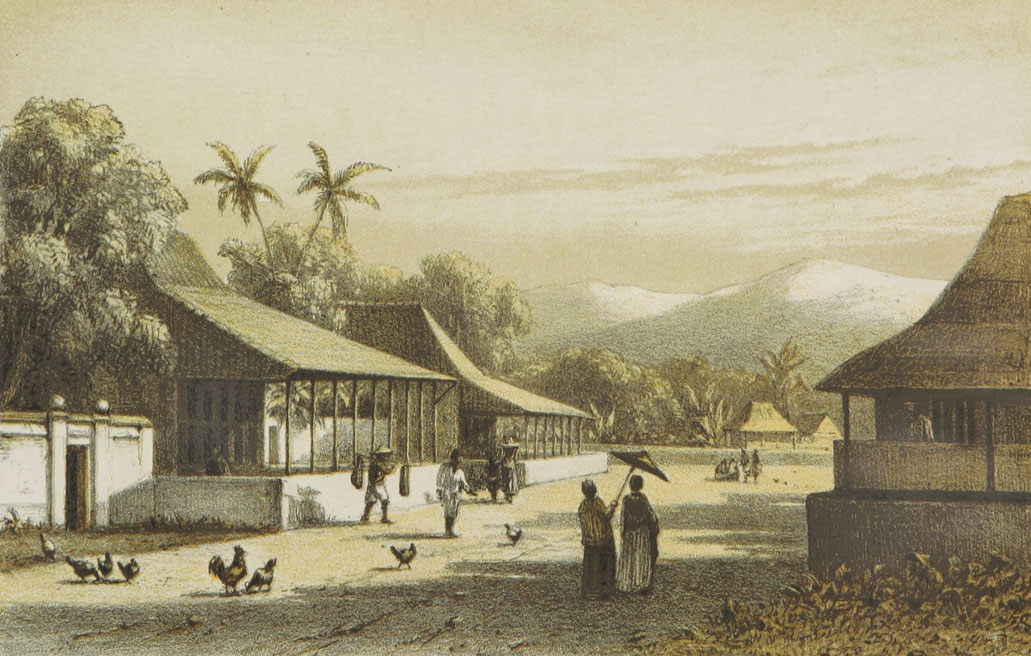

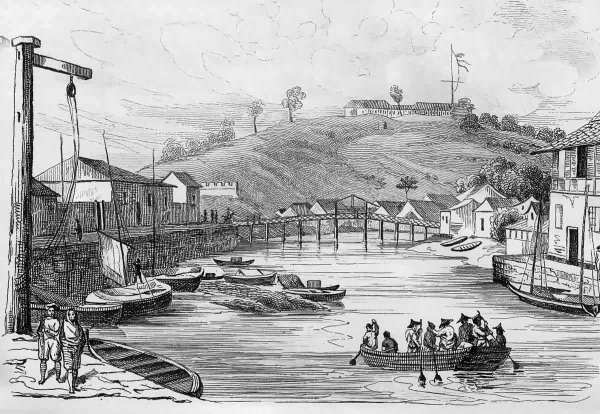

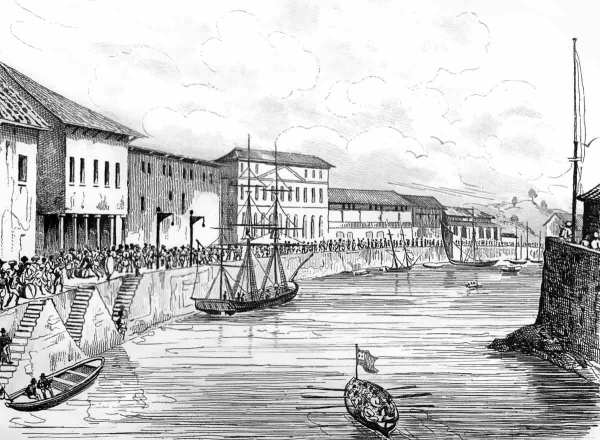

On 3 December, the Patriot arrived in the Batavia Roads and made her way up the crocodile-infested main canal. On both sides, Javanese and Chinese kampongs were visible among the trees. Augustus Prinsep, who visited the city in 1829, described Batavia as a ‘proverbially unhealthy colony’4 and the ‘stagnant depot of Dutch commerce.’5 He gives this description of the approach:

There is a bar at the mouth of the river, over which the water is so shallow, that loaded boats can only pass at high tide; for which reason two long quays are built on either side of the entrance, a considerable way into the sea.6

The two exceptionally long jetties provided sufficient wharfage for one of the world’s busiest ports. Ships with the ensigns of many nations travelled half way around the world to anchor in its roads. The English naturalist, George Bennett, who visited Batavia in 1833, commented on the ‘dead and putrid bodies of dogs, hogs and other animals floating in the river and impeding boats in their passage.’ The crocodiles on the mud banks, however, did remove the ‘putrefying substances’.7

Batavia’s reputation as one of the world’s unhealthiest cities was well known. It had nothing to do with its temperature, which averaged 85°F, and everything to do with overcrowding and its swampy locality, exacerbated by the Dutch penchant for canals. Batavia, like Calcutta, suffered from mysterious and unhealthy ‘emanations’ that were thought to come from a large marsh which lay between the town and the sea. No one at that time linked malaria to mosquitoes, or realised that boiling all drinking water could reduce or prevent many complaints such as dysentery. The stagnant swamps and canals were the prime sources of Batavia’s malignancy.8

By 1835 the Dutch colonists had long since moved their homes to suburbs away from the swamps, with the result that Old Batavia was now used solely for business. Bennett praised the new suburbs for their shady arbours, flower-filled gardens and fine Dutch residences. Visiting ships’ crews continued to regard the rest of Batavia as dangerously unhealthy.

When news of the sudden arrival of the five shipwrecked survivors spread around the port, an Englishman had a chat with them. There were at that time only seven or eight English merchants living in Batavia, and its possible he was one of them. Alternatively, he was the master of a visiting ship. All five sailors were present and gave a brief account of what had happened to their ship. The Batavia correspondent immediately sent a summary of the interview to the Messrs Gledstanes:

We have just received some intelligence respecting the unfortunate Barque Charles Eaton, which we hasten to impart to you. Five of the crew arrived here yesterday in a coasting vessel called the Patriot, commanded by Capt. Clunie [sic] from Amboyna and the following is their account of the loss. It appears that, when the Charles Eaton was close to the entrance of Torres Straits, she mistook a light of land for them and, before the ship could be put about, struck on the reef, the sea breaking heavily on them at the same time when the long Boat was instantly stove. When the five sailors left the Ship in the Jolly Boat, Capt. Moor [sic] was clinging to the Main chain9 and a Capt. D’Oyly, one of the passengers with his Lady and children, standing near him. The Sailors think all remaining on board must have perished; and, the sea being tremendous, the ship must have gone to pieces.10

This account includes what appears to be a deliberate deception. They had used the largest of the ship’s cutters, capable of taking at least another six people, and not the tiny jolly boat as they claimed.

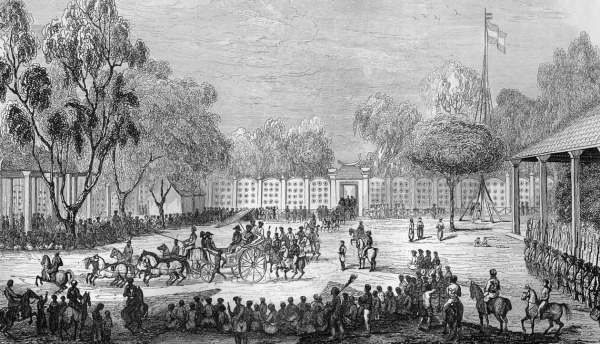

The Governor-General also received the news of the sailors’ arrival, and ordered them to appear before a magistrate the next day. Before that could happen, Piggott was hospitalised with a fever that would prove to be fatal. The remaining four were interviewed at the suburb of Weltervreden, where the Dutch administration had its offices, a courthouse and the Governor-General’s staterooms. A few days later, Governor-General Baud sent a dispatch to Lord Bentinck in Calcutta, which contained the sailors’ deposition. Additional copies reached Amsterdam and, eventually, London. Richard Quin, speaking also for the other three sailors, declared that on 15 August 1834, at about 10 o’clock in the morning, their vessel struck on a reef, called Detached reef, at the entrance to Torres Straits.

On being asked whether they had not been able to save any more of the unfortunate passengers and crew, they answered that such was quite impossible, as they could not pull up the boat against the strong current; and no individual among the passengers or crew would venture amidst the heavy breakers to reach the boat by swimming.11 That they in consequence are unable to say or state what is become of the captain, passengers, and the rest of the crew; they can only affirm, that at the time Richard Quin and James Wright left the wreck, all the passengers were alive on the forecastle of the vessel, with the exception of one sailor named James Price, who was drowned by the smallest of the cutters swamping at the time she was lowered.

And the appearants further declared, that not seeing any possibility of saving any more of the ship’s company, and not perceiving a single person in the morning of the next day on the wreck,12 they concluded that these unhappy persons had been washed off the wreck by the increasing swell of the sea in the night, and all found a watery grave; that they took to sea on Sunday morning, the 17th of August ensuing, without being provided with a compass or any other nautical instruments. The whole of their provisions consisted in about 30 lbs of hard bread, one ham, and a keg containing about four gallons of water, which had been immediately put in the boat before she was lowered.13And the appearants further declared, that not seeing any possibility of saving any more of the ship’s company, and not perceiving a single person in the morning of the next day on the wreck,12 they concluded that these unhappy persons had been washed off the wreck by the increasing swell of the sea in the night, and all found a watery grave; that they took to sea on Sunday morning, the 17th of August ensuing, without being provided with a compass or any other nautical instruments. The whole of their provisions consisted in about 30 lbs of hard bread, one ham, and a keg containing about four gallons of water, which had been immediately put in the boat before she was lowered.13

The lengthy deposition continued with details of their time on Yamdena and their rescue. Baud remarked in his own dispatch to Lord Bentinck that it encouraged him to hope the rest of the crew and passengers might be on islands easily attainable in an open boat from the Torres Strait.14

The deposition circulated among relatives and friends of the missing passengers and crew, but only after the shorter first version sent to Messrs Gledstanes by a correspondent had already done the rounds. Now everyone was talking and writing about what appeared to be the mutiny or desertion of the surviving sailors.

The wreck of this particular barque (unlike the multitude of other ships that met a similar fate in 1834) attracted an extraordinary amount of attention, in four countries and at the highest levels of government. Partly it was because of the persistent rumours of survivors, partly because of reports that it had been sighted ‘high and dry on the Barrier reef in Torres Strait’,15 and partly because the D’Oylys had contacts in high places beyond their own modest station. History has tended to exonerate the five sailors and dismiss any charge of desertion, despite the obvious lies in their deposition. It would be pointless to condemn the men on the grounds of ‘women and children first’ since no such moral principle then existed. In the wake of any shipwreck, every Jack was as good as his master.

…..

Notes to Chapter 8

- See Hamilton, East India Gazetteer, vol. 1, London: W. H. Allen, 1825, pp. 25–27 and Swadling, Pamela, Plumes from Paradise, Queensland: Papua New Guinea National Museum with Robert Brown & Assoc. Pty Ltd, 1996, pp. 34–44, for brief histories of Ambon and the spice trade.

- Batavia deposition, William Bayley File, Dixson Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, A1074.

- Phillip P. King, Capt. R. N., F. R. S. (ed.) ; A Voyage to Torres Strait in Search of the Survivors of the Ship Charles Eaton, which was Wrecked upon the Barrier Reef, in the Month of August, 1834, in His Majesty’s Colonial Schooner Isabella, C. M. Lewis, Commander, arranged from the journal and log book of the Commander, by authority of His Excellency Major-General Sir Richard Bourke, K. C. B., Governor of New South Wales, etc, etc, etc. Sydney: E. H. Statham, 1837., pp. iii–iv.

- Augustus Prinsep, Journal of a Voyage from Calcutta to Van Diemen’s Land : comprising a description of that colony during a six months’ residence : from original letters, selected by Mrs. Augustus Prinsep, 2nd edn, London: Smith, Elder and Co., 1833, p. 30.

- Prinsep, p. 30.

- Ibid, p. 34.

- See George Bennett, F.L.S., Wanderings in New South Wales, Batavia, Pedir Coast, Singapore, and China; Being the journal of a naturalist in those countries, during 1832, 1833, and 1834, 2 vols, vol. 1, London: Richard Bentley, 1834, pp. 350–71 for a record of his visit to Batavia.

- See Hamilton, East India Gazetteer, vol. 1, London: W. H. Allen 1825, pp. 86–96 for a lengthy description of Batavia in the first quarter of the nineteenth century.

- The captain and his passengers were standing next to a set of strong, linked ropes (shrouds, main chain) that extended from the main mast to the side of the ship and provided the mast with one of its main supports. There is, of course, an identical set on the other side. They are the supports that we are all familiar with that look like linked rope ladders.

- William Bayley File, Gledstanes to Bayley. Dixson Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, A1074.

- My italics. This was not true but the sailors were not about to admit that they had abandoned some of their comrades.

- My italics. The sailors did not stick around for long enough to find out what had happened to rest of the ship’s company, and certainly not for an additional day.

- Batavia deposition, William Bayley file.

- Phillip P. King, A Voyage to Torres Strait, preface, p. iv.

- Ibid.

………..

…

Chapter 9: the convict Ship Mangles

It was late afternoon on 18 September 1835 when Waki climbed a hill on Mer, an island in the Torres Strait and the largest of the Murray Islands group. There was merry-making going on in the village below but he did not feel like joining in.1 Suddenly he saw a ship approaching the island. From his vantage point on the hill he was the first to see it. He tried to attract the sailors’ attention with silent waving, but the ship was too far away. Soon the rest of the islanders saw the ship too and his father, Duppa, took Waki back to his hut in their compound, where the women painted his skin mahogany and streaked his face and hair with red and yellow ochre. Tassels of plaited grass were hung from each ear and shell ornaments festooned his body. Waki and Duppa then gathered on the hill with the rest of the villagers. The ship came closer and everyone broke branches off trees and began waving them furiously, to show they wanted to trade.

The Torres Strait Islanders were experienced traders. Not only did they have their own inter-island network, but they had also been trading with Papuan villagers, Australian Aborigines and the occasional visiting Malay-Indonesian prau for many centuries. European trading vessels were comparative latecomers to their network, when the trading techniques employed by the islanders were well honed. They would attract the attention of a passing vessel to indicate they had goods to trade and as soon as the ship had anchored, they would begin loading canoes with their stockpiles of brown trepang and the decorative shells from the tortoiseshell turtle. Trade would be brisk and they would drive a hard bargain, with iron goods preferred in exchange. They had no knowledge of the true value of tortoiseshell on the Chinese market but they sure did know the value of a good iron tomahawk and were in no doubt they were getting the better deal.

To Waki’s great joy, this ship did drop anchor some distance from shore but no boat pulled away from it. He went down to the beach with Duppa, collecting on the way his friend Uass, and with other islanders they waited until it was dark, shouting ‘Tooree, tooree’ i.e. ‘Iron, iron’ to show they wanted to trade for iron – axes, knives and pots. Still no boat pulled away from the vessel. Sometimes they called out ‘Wallee, wallee’ for clothing, but iron goods were always preferred. The monotonous and constant chant of so many united voices carried across the waves to ships often anchored a mile offshore.

By sunset, their arms were tired from waving branches and their voices hoarse from shouting, so everyone retired for the night. They would take the initiative and row their canoes out to the ship tomorrow, in the expectation that the ship really did have goods to trade. All along the beach, families gathered around fires for their evening meal.

The ship at anchor off their island was the Mangles, Captain William Carr, a regular trader around the seas off northern Australia. Carr had his only child, an illegitimate son called William Carr Jnr, with him. His wife, Anne, may also have been enthroned in the cuddy since it was her habit to share his travels. She was Carr’s ‘beloved wife’ but he was similarly fond of her sister, Elizabeth Robinson, and had set up an amicable threesome in Limehouse, London.2

The Mangles had just completed her seventh voyage to Australia as a convict transporter. If you knew what to look for, the tell-tale signs were there: barred hatches; high bulwarks, exercise yards and a well-armed crew. Aside from that, she was arguably the biggest ship at that time to regularly visit the Murray Islands.3 Originally built at Calcutta in 1802 for the F. & C. F. Mangles shipping company to service the India trade,4 she had three decks above her cargo hold and had been registered to carry almost 600 tons burden. Her elevated poop at the stern was particularly commodious and comfortable. She was built from Indian teak but nevertheless boasted a copper-clad sheath on her hull to repel wood-boring worms, and by some trick of design she was also incredibly fast, consistently making the journeys to Australia in almost record-breaking times.5 Her past voyages had been occasionally marred by the usual infections and fatal accidents but on this particular voyage she had delivered 310 convicts to Van Diemen’s Land with no loss of life.

It was voyage number four for Carr as her captain (he was formerly the chief mate). He was a man of good character but the constant exposure to so much human misery may have left its mark. He had a reputation for catering for the well-being of his convicts in terms of his ship’s unusually good accommodation, plus he supplied materials for self-education and self-entertainment on the voyages out, but in every other respect he was, first and foremost, a businessman. Overheads were minimised by avoiding calls to any ports en route for fresh produce unless scurvy outbreaks compelled him to do so. He was part-owner of the Mangles but the current voyage would be a financial success and in 1839 he became her sole owner.6

For most of her years as a convict transporter, the Mangles had attracted little attention, despite the fact that she usually lingered in Sydney for long enough to fill at least part of her large hold − by no means an easy achievement given that Carr didn’t accept whale oil, preferring bales of merino wool instead. On this particular voyage, however, the Mangles got a fair bit of newspaper coverage, primarily because her prisoners had included about 140 juvenile chimney sweeps aged between 16 and 20. According to the Sydney Herald (31 Aug. 1835):

The prisoners by the Mangles, we regret to say, are to be numbered among the most miserable of mortals, and by far the worst sample of human kind that has yet been brought to our shores. They consist for the most part of poor decrepit chimney sweepers thrown out of employment by the operation of the late act7 and those who do not belong to this unfortunate class of men are of a still uglier race, inasmuch as not being so black outside, they are yet blacker within. It is ‘too bad,’ as the late Lord Liverpool said, to father these poor creatures upon us, and attempt to make us pay for them into the bargain. – Courier.

What the penal communities needed were tradesmen, or mechanics as they called them, and what they got was almost half a shipload of bedraggled juvenile sweeps.

On a previous voyage, in June 1833, Carr had called at Mer and collected large quantities of tortoiseshell and curios for the Canton market, as well as coconuts, yams, sweet potatoes and bananas for the ship’s stewards.8 Now he was back for more of the same. He did not entirely trust the Murray Islanders, however. His normal ship’s compliment was 48 but he had lost six sailors at Hobart Town. The Hobart newspaper Colonial Times reported (11 Aug. 1835): ‘Three seamen had been removed from the Mangles at Hobart Town for most violent outrages and insubordinate conduct on board that ship while lying in the harbour.’ They were jailed for three months. The remaining three must have absconded.

Carr, who had sailed direct from Van Diemen’s Land, was troubled about his reduced ship’s company and decided to deal with the islanders in the morning. In the meantime, he increased the night watches in case of trouble.

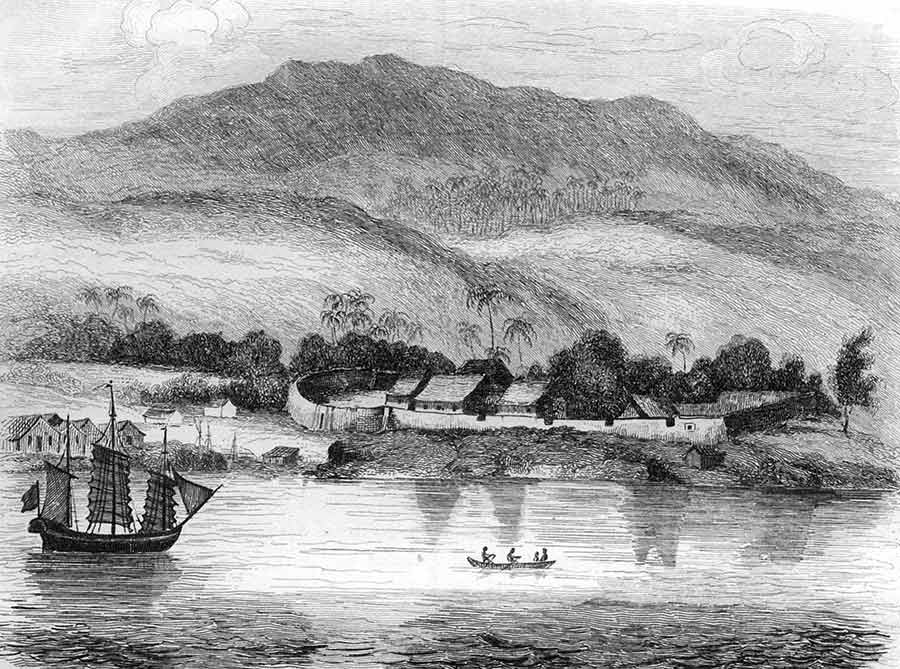

Mer’s natural beauty has always won compliments from visitors. The island is formed from volcanic rock, ground down in many places to fertile soil. Its most striking feature is its silhouette, dominated by Gelam, a majestic hill that sweeps down to a smaller hill near the centre. The southwestern end of the island is quite rocky but at the northeastern end, there is a large plateau of fertile and densely cultivated land, extending right down to the island’s northern beaches.

A long narrow reef extends from the southeastern corner of the island, while not far from its southwestern corner are two smaller islands, which with Mer make up the Murray Islands group. These two sister islands are separated from Mer by a wide deep-water channel but joined to each other by a sand bank and a single, enclosing reef.9 Douer, the larger of the two, is made up of two grassy hills with a fertile valley in between, while Waier is the cone of an ancient volcano. In 1835, there were huts and coconut trees in Waier’s more sheltered recesses.10

William Brockett, a sailor who visited Mer nine months after the Mangles, described an island ‘thickly covered with trees of various descriptions and shades’11 with coconut plantations spreading up the lower reaches of the hills. Along the fine beaches was an almost unbroken line of thatched beehive-shaped huts, grouped into villages. Drawn up on the sand were many large outrigger canoes, while bamboo fences protected the beachfront gardens and plantations from the monsoonal gales that regularly blew in from the sea. When the crew of the Mangles changed watch at dawn on the following morning, their gazes took in a distant but tantalising scene.

Soon after sunrise, 14 or 15 large canoes made their way out to the ship. Each was carrying about 16 men, many of whom were carrying bows and arrows and spears. It looked as if a fearsome armada was about to engulf the ship but the canoeists were coming out to trade and their weapons were part of the goods they were carrying for barter. The Mangles, once they were close enough to identify her, was a familiar sight and they were relaxed about her arrival.

Their 20-metre canoes had a single sail and two outriggers, which made them virtually unsinkable. Large platforms displayed their trade goods, including some that were popular souvenirs. Men with long paddles were standing fore and aft of each platform, propelling their craft through the water. With one exception, all were Mer islanders. One of the last canoes to draw alongside the ship dropped directly under the stern and the sailors on the poop deck could see that one of the paddlers, though naked like the rest, was a white man.

It was Waki. The sailors judged him to be between 18 and 20 years old, of stout build and about 5’8″ tall (173 cm). His skin appeared to be stained to a deep brown and his hair was so encrusted with red ochre its colour was impossible to judge. His only clothing was the usual protective waistband made from turtle skin, commonly worn by the male islanders, and he seemed by his gestures to be just as keen to trade as everyone else.

For the moment, Captain Carr was interested in more pressing matters and took little or no notice of the white man. Most of the canoes had gone to the starboard side, where the crew had lowered a quarterboat half way down for the purpose of trade. It was ‘I’ll show you mine if you show me yours’ time. Carr and his officers stayed on the starboard quarter, bartering for tortoiseshell and curios. They watched the islanders carefully and kept their guard up until several of the canoes had returned to shore. Carr was troubled. He had often traded at Mer and always allowed on board an old man called Madoo, whom he took to be one of their chiefs. Madoo always offered himself as a hostage to guarantee peaceful trading. ‘He is a well-conducted man,’ Carr would later explain, ‘but until this voyage he uniformly recognised and spoke to me. Upon this occasion, however, he would not speak to me at all; but he afterwards, I am told, spoke of me and Mrs Carr.’

Waki, meanwhile, had called for a rope and one of the sailors threw one down to him, which he grabbed and tried to use to climb aboard the half-lowered jolly boat. ‘But I had sprained my wrist, by a fall a day or two before,’ he explained many years later, ‘and waving the branch had made it exceedingly painful, so that I could not climb. One of the crew held out a roll of tobacco to me, but I could not reach it; so I asked him to lower the boat for me to get in.’

Carr turned around just in time to see Waki making one attempt to climb the rope but it broke and he fell back into his canoe. The sailors were in the act of lowering the jolly boat closer to sea level when their captain abused them. One of them would later state that as far as he could recall, Carr had cried out, ‘Damn the man, I do not want the man I want tortoiseshell’. Other witnesses would later claim that Carr gave the order to lower the boat. The trade going on around him distracted Carr. He was either not fully aware that the man trying to board was a European, or else he was unconcerned, perhaps even disinterested. He wanted to finish his business quickly before any trouble erupted.

One of the sailors asked Waki how he came to be on the island and he explained that he was a castaway but Duppa and the other men in his canoe were pulling him back and in the resulting confusion, his lengthy but somewhat garbled reply was misunderstood. The fourth officer, Jim McMicken, then asked Madoo how many white people were on the island. The old man quietly approached, touched McMicken’s face to indicate, ‘white people like you’ then held up both hands. McMicken concluded that Madoo was trying to tell him that there were another eight or ten white people ashore.

Duppa’s canoe had drifted a short distance from the stern. When he was finally free to do so, Carr turned his attention to the white man. He ordered that the cutter be manned and armed, sending ‘the second officer, the boatswain and six men to take him at any price’. But when Duppa and his friends saw the sailors putting pistols and naked cutlasses into their cutter they became alarmed. ‘They thought mischief was intended to me and to themselves,’ Waki later explained. ‘They immediately let go the rope, and paddled towards the shore. I stood up in the canoe, but Duppa took hold of me and laid me down in the middle of it.’ The cutter, he said, made only a half-hearted attempt to overtake his canoe.

According to Carr, the men in the cutter caught up with Duppa’s canoe and hooked it with their boat hook. The second officer, Bill Eames, asked Waki to step into the cutter but Waki pointed to one of the other islanders and replied, ‘Take that man, he will go with you.’ ‘No’ said Eames, ‘I am come for you, and you I will have.’12 Waki, Carr later claimed, then immediately threw down the paddle he had in his hand and dashed under the canoe’s platform amidships. The second officer contradicted his captain by claiming that Waki dived overboard and swam away. Carr ordered the cutter’s return, proclaiming, ‘If he prefers a life with savages, let him remain.’ He was puzzled all the same, he would claim, for ‘what his motive could be for not coming into my boat, I am at a loss to conceive’.13

Duppa’s concern for Waki’s wellbeing was based partly on his fear of the white man’s firearms and partly on the perception among Torres Strait Islanders that ‘white people live always in ships, and possess no terrestrial home, and that they subsist upon sharks, porpoises, and dogs’.14 Their lifestyle excited no envy.

McMicken now told Carr that the white man was a shipwrecked Englishman and that Madoo had indicated to him that there were eight or 10 other survivors on the island. Carr spent the next two hours pacing up and down the deck trying to decide what to do. His chief mate suggested he detain Madoo until the white man had been handed over but the captain ignored his advice and the opportunity to use the old man for ransom passed when Madoo, satisfied that the trading was over, returned to Mer.

Finally the captain manned and armed the cutter again, put himself in charge of her and sailed close to the shore. For two hours he scanned the beach with his spyglass looking for more Europeans and ‘observed a matted screen not quite reaching to the ground, and saw among the native feet passing to and fro, some white feet, and what seemed to him part of a lady’s petticoat.’15 Waki was watching him and thought the captain had come to the shore to shoot birds, something that ships’ crews often did to supplement their rations. He was, he later explained, ‘kept among the bushes all this time, by Duppa and his sons; but I could plainly see every thing that took place.’ The cutter’s crew was armed with pistols but fired no shots at birds or any other target.

A standoff now developed between the men in the cutter and a large group of people on the beach, with Carr making signs to the watching crowd to come near his boat and the islanders indicating that they wanted Carr and his men to come ashore. In an attempt to break the impasse, a man emerged from behind one of the bamboo fences carrying a young boy on his shoulders. He walked along the beach towards Carr, making beckoning motions as if to say, ‘Come!’ The little boy was Waki’s friend Uass and he was as brown and naked as any child of the Torres Strait; would have passed for one were it not for his blue eyes and flaxen hair. From his vantage point behind the bushes, Waki could see what was happening and believed he understood. ‘I had often mentioned to the natives that the white people would give them axes and bottles, and iron, for the little boy,’ he later said. ‘I told them his relatives were rich, and would be glad to give them a great deal if they would let them have him back.’ The men on the beach were terrified of artillery fire. Waki was in no doubt that if enough axes and iron goods had been handed over at that point, both he and Uass would have been given up in exchange.

Carr could see that the boy was small and guessed him to be less than three years old. The child now beckoned to him to land, speaking words the captain couldn’t understand. An offer to swap the boy for iron axes drew no obvious response from the assembled crowd, who stood around silently watching Carr bobbing around in his cutter and waiting to see what he would do. Carr now saw that several canoes were trying to get to the seaward of him and became afraid his party would be cut off from his ship. Before he hastily retreated he wrote a message on his hat promising to make known what he had seen and threw it on the shore. The cutter then returned to the Mangles and Carr spent the rest of the day scanning the island with his spyglass but could see no more white people. He remained off Mer all night, ‘thinking it might be possible for some of them to make their escape.’ At nine o’clock the following morning he weighed anchor and sailed away. Waki watched the ship go with a heavy heart, convinced that all hope of deliverance had gone.

….

Notes to Chapter 9

Unless otherwise indicated, this chapter has been constructed from three main sources: John Ireland, The Shipwrecked Orphans . . . New Haven: S. Babcock, 2nd edn, 1845, pp. 47–48; the London depositions of the captain and crew of the ship Mangles, The Times, 5 Nov. 1836; and Ireland’s London deposition, The Times, 31 Aug. 1837.

- According to William Brockett, John Ireland confessed that during his time upon the island he had been compelled to marry. William Bayley file, Dixson Library, State Library of New South Wales, Sydney, A1074. It is possible that the merrymaking was Ireland’s own wedding, since it was the custom at Murray Island for bridegrooms to go off alone and hide among the bushes until they were summoned to return and fight to claim their new bride.

- UK National Archives UK, May 1841.

- The Australian newspaper, 18 Nov. 1824, commented of her: ‘She is larger than any ship that ever sailed from this port laden with colonial produce. Her burden is not less than 600 tons. Her accommodations must be wonderfully superior to those of small ships – calculated, if any thing is, to lessen materially the privatations to passengers’.

- The ship Mangles had a varied ownership can be tracked through Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping. Also see information on the Mangles shipping company on Wikimedia.

- Sydney Gazette 4 Nov. 1824 for a description of her copper-clad hull and three decks.

- Lloyd’s Register of British and Foreign Shipping, 1840; Carr’s will in the UK Archives.

- The Chimney Sweepers Act 1834 stipulated that apprentice chimney sweeps had to be over the age of 14 and no master was allowed to employ more than six apprentices. The Act prevented child labour exploitation and slavery but it did reduce employment opportunities for juvenile chimney sweeps. The government’s solution was to ship them off to Australia.

- Ian J. McNiven, ‘Torres Strait Islanders and the maritime frontier in early colonial Australia’, in Lynette Russell (ed.), Colonial Frontiers: Indigenous-European Encounters in Settler Societies, Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2001, pp. 187.

- J. Beete Jukes, Narrative of the Surveying voyage of H.M.S. Fly, commanded by Captain F.P. Blackwood, R.N. (during the years 1842–1846), 2 vols, London, 1847, pp. 196–97.

- See Jukes 1847, pp. 196–97; W. E. Brockett, Narrative of a Voyage from Sydney to Torres Straits in Search of the Survivors of the ‘Charles Eaton’. Sydney: printed at the Colonist, 1836, p.24; Capt. C. M. Lewis, ‘Voyage of the Colonial Schooner Isabella.—In search of the Survivors of the Charles Eaton’, Nautical Magazine, vol. VI, 1837, p. 662 for descriptions of the Murray Islands in 1836.

- Brockett 1836, p.12.

- Thomas Wemyss, Narrative of the Melancholy Shipwreck of the Ship Charles Eaton . . . 2nd ed., Stockton-on-Tees: J. Sharp, 1884, pp. 18–19. Extract from a letter written by William Carr and also published in a number of newspapers.

- Wemyss 1884, pp. 18–19.

- Ibid.

- Lewis 1837, p. 754.

…

.

..Chapter 10: Coupang and Canton

…

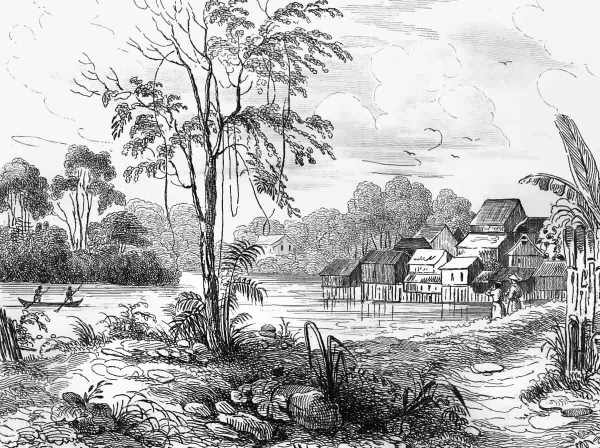

After a brief stop at Booby Island, where he read the logbook kept there but made no entry on what had occurred at Mer, Carr sailed directly to the Dutch colony of Coupang (Kupang) in West Timor, a popular victualling port for whalers and trading ships. Free water could be got from a pipe on the beach and fowls, coconuts and bananas were on sale at the local markets. Rum was available from the Chinese trade stores but it was expensive. A better buy was the locally fermented coconut wine, which was cheap but potent. Many – if not most – of the European sailors who worked the Timor and Arafura seas and victualled at Coupang were intoxicated for the duration of their stopovers. They were an insubordinate and undisciplined rabble but most ship masters seemed to tolerate their behaviour as a necessary respite from their otherwise dangerous and arduous lifestyle. Their often obnoxious and drunken misconduct, however, did make them easy targets for murderous pirates.1

Chinese capitalists were much more successful at colonising South-East Asia than European merchants and governments and this was nowhere more evident than at Coupang, where they owned all the shops and most of the money. Unlike the Dutch and English, the Chinese shopkeepers had no interest in being soldiers and tax collectors. Nor did they waste their profits on lavish homes. Brockett, who visited the town a few months later, unkindly commented on the number of rich Chinese living in hovels, ‘not much superior to an English pig-sty.2

Coupang had never been a profitable colonial entrepôt. On a small headland along the beach the Dutch had built their Fort Concordia, a small and inferior structure manned by a few dozen Timorese soldiers and a couple of Dutch officers, in charge of just two mounted cannons. Although the Dutch claimed to have control over the west and south sides of Timor, their influence was limited to the town. If its 20-or-so Dutch residents had vanished one night the town would simply have carried on without them. The miserable fort and its two guns, on the other hand, were vital to the town’s survival, offering traders and whalers protection from the marauding pirates. Many whale boats used the port as their home base while they fished the Arafura and Timor seas.

The town was little more than two long, parallel dirt streets, stretching along the southern side of Coupang bay and lined with Chinese-owned houses, shops and warehouses. The dwellings of the handful of Dutch administrators were clustered around a square behind the town where the Resident had his large government house, and there was also a Dutch Reform church and a school.

The Malay Timorese who daily invaded the town with their produce had long ago emigrated from other islands in the Indonesian archipelago. They lived in kampongs on the outskirts of Coupang and in all the fertile valleys, building neat white houses with red-tiled roofs and surrounding them with plantations and vegetable gardens. In the wetter, deeper valleys they had planted rice paddies, ringed with tropical vegetation.3 The mountainous aspect and green paddy fields were a nice contrast to the flat and uninviting Australian coastline.

The original inhabitants of the island had long since been dispossessed of their fertile lands and driven into the barren interior. Physically they were Melanesians, with attractive brown complexions and crisply frizzy hair. They had their own language, were head hunters, and shared with the Tanimbar Islanders a love of gold and silver ornaments. With no land left to them worth cultivating, their lives were frugal, their villages being not much more than clumps of a few thatched-roofed but open-sided shelters. Wealthy and cruel rajahs had enslaved many of them. Indeed, it would be fair to say that most of the Timorese at that time were under the control of the island’s rajahs.

Coupang was the closest safe haven for passengers and crews shipwrecked on the Barrier Reef. The fact that so many of them successfully rowed the 1200-mile (2000-km) journey to the little seaport in open boats seems amazing. Fortunately the strong, west-flowing currents made the journey less arduous than it might appear. In 1832 the 36-man crew and one female passenger from the Flora shipwreck made it safely to Timor in a single longboat. Their achievement was both remarkable and routine. Coupang’s residents were used to the sight of sunburnt crews in longboats or cutters, with blistered hands and salt-encrusted eyelashes, rowing like skeletal zombies towards their bay.

Carr was to discover when he got to the town that a shipwrecked crew had arrived there the previous day. It was Captain Cobern and the exhausted sailors of the schooner Jane and Henry, recently wrecked on the Barrier Reef. Cobern, having successfully negotiated a passage through the Barrier Reef to the Torres Strait in the company of the Augustus Caesar, had been game enough to tackle it alone on his second trip a year later – with disastrous results. Cobern later gave an account of his schooner’s final voyage.4 The Jane and Henry had left Sydney on 23 August 1835, bound for Batavia. At ten o’clock on the evening of 11 September it was in the vicinity of Sir Charles Hardy’s Island when it struck a small detached reef called Yule Reef, a few miles to the seaward of the Barrier Reef. ‘The vessel soon bilged,’ wrote Cobern, ‘the sea making a clean breach over her so that all hope of saving her was abandoned.’

At daylight Cobern and his ship’s company of six sailors and three boys launched the longboat and set off for Timor. After brief stopovers at Forbes Island, Bird Island and Escape River (where they found fresh water), they arrived safely at Coupang on 30 September, having been rescued by the Dutch brig-of-war Meerman, Captain Enslie, off Bali island. Enslie had been charting the West New Guinea coastline and the western approaches to the Torres Strait when he spotted their longboat.5

At Coupang the shipwrecked sailors found a British barque and two whalers and the three commanders took pity on the Jane and Henry crew and ‘vied in hospitality with each other,’ wrote Cobern, supplying the distressed survivors ‘with clothing and all that was necessary for comfort.’6 Carr made a statement to the Dutch resident at Coupang about the two white boys he had seen at Mer, which must have been relayed to Batavia. The captain had not yet had time to make up any stories to portray himself in a favourable light, so this statement may be one of his more accurate versions of events and his story did vary with each retelling. In it he states that the cutter sent to rescue the white man at Mer had only been allowed to approach to within speaking distance. The white man ‘had called out that he would not be allowed to go–that he was one of the Charles Eaton’s crew, and that there were more of them upon the island.’7

Later Carr took Cobern, his crew and their long boat aboard the Mangles and transported them to the northern side of the Somlach Straits. Any fly on the wall would have been privy to some interesting conversations in the Mangles cuddy. The two captains had interesting stories to exchange. Carr and his men were soon put in the picture about the wreck of the Charles Eaton the previous year, although some of the Mangles crew formed the impression that the disaster was recent. Five days after leaving Coupang their long boat was fitted out with all necessary supplies and relaunched, and Cobern and his crew spent the next two days rowing to Sourabaya (Surabaya).8 The owners of the shipwrecked schooner were obliged to pay the cost of transporting their sailors until they eventually arrived back at their home port of Cape Town. Carr, however, being part-owner, extended a small charity to Cobern and his men. He was steering clear of Sourabaya and possibly avoiding Indonesian customs so that he wouldn’t have to declare his tortoiseshell.

A few days later a troubled Carr wrote letters while he was sailing past the island of Lombok, addressed to the editors of the Canton Register and the Singapore Chronicle. After he had dropped off the Jane and Henry sailors he continued to tramp and trade around the islands of South-East Asia for many months. Carr at this stage was already showing signs of being defensive about his actions. If we seek the simple truth about what happened that day at Mer, we probably can’t get any closer than this: Carr was far too timid and fearful in his dealings with the islanders and, later, too embarrassed to admit it. He was travelling with his son and that may have made him overly cautious. Already in advanced middle-age, he would die in 1841 with his reputation in tatters.9

Meanwhile, the Dutch Governor at Batavia, acting on a request from the Governor-General of Bengal but also, presumably, Carr’s report at Coepang about sailors being held on an island, sent out their own scout-and-rescue mission. The outcome was both fortuitous and disastrous:

The Dutch barque, Alexander, Captain Harris, respecting which there have been such numerous and frequent surmises, we also learn, with all her crew excepting three sailors, had been cut off by the natives of the Aroo Islands. The Dutch frigate, Diana, which had been away in that direction in search of the Charles Eaton, touched at one of the Islands on her return, and there found the three men who had escaped the cruel fate of their comrades. The Diana forthwith manned and armed her boats, and sent them on shore, and a scene of retaliation then ensued . . . – Singapore Free Press.10

The village was actually on the island of Larat. According to a later account, the village and all the plantations and coconut trees were burnt down and ‘some elderly persons who were unable to leave their huts perished in the flames.’11

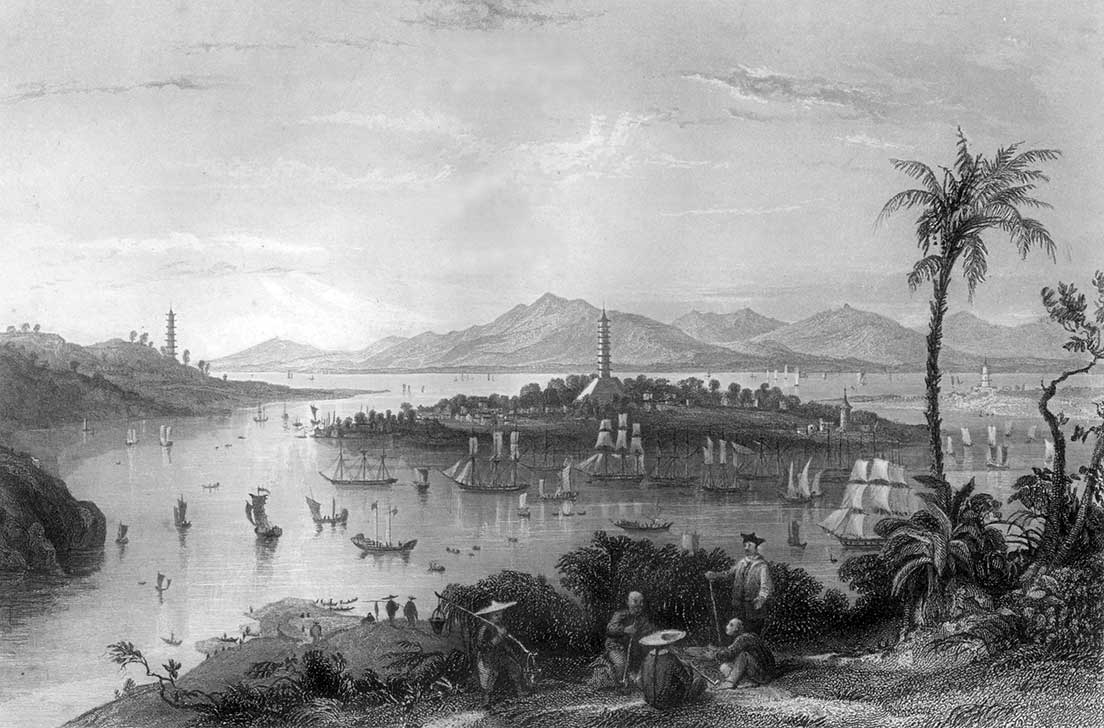

In the second week of February 1836, Carr’s ship took on board a Chinese pilot and sailed up the Canton (Guangzhou) river to the island of Whampoa. Both sides of the wide entrance to the river were guarded by forts, their main purpose being to prevent any illegal cargo – especially opium – from being smuggled into China. Captain Carr was no stranger to Canton; he had visited it many times. When he reached Whampoa, downstream from Canton, he knew that was as far as his ship was allowed to go. The Mangles had to join the many other merchant ships at anchor there. Whampoa was the docking zone for the good guys, engaged in legitimate trade with China. The bad guys, the American’s and English East India Company’s outlawed opium ships, gathered like vultures in a harbour north of Macau, or lurked behind the island of Lintin, waiting for the opium runners to sneak out to them under cover of darkness.12 Carr, however, had his hold filled with tortoiseshell, trepang and other marine delicacies and if he wanted to do business at Canton, all he had to do was travel by barge boat (sampan) up a junk-crowded river and bargain with Chinese merchants for the legitimate sale of his cargo in exchange for tea. The usual time-frame for such transactions was about six weeks because the custom controls were so stringent.

Canton was a sectioned-off piece of land allocated to overseas merchants for the sole purpose of trade. Much of its space was taken up by the hongs, or warehouses, of many different nations, with the East India Company’s hong by far the most impressive. There were two wide shopping streets, called Old China street and New China street, where foreign tourists could take their choice from the best that China’s artisans had to offer, including carved sandalwood chests and lacquered furniture. Entry to the walled city of Guangzhou was via a large gate and there were other smaller gates around its perimeter. All were heavily guarded. No foreigner was allowed to enter the Chinese city without permission and that was rarely granted. The best that most visitors could hope for in 1835 was a panoramic view overlooking the city, from the balcony of one of the hongs.13

The legitimate Chinese merchants and traders weren’t that interested in European goods and the balance of trade, largely through the export of tea, was in Canton’s favour. The EIC had established opium plantations in India expressly for the illegal Chinese market, while American ships wanting to challenge their monopoly had to fill their holds with opium from the poppy fields of Turkey and Afghanistan. It was an extraordinarily long detour, travelling to China via the Middle East, but worthwhile for the American shipowners nonetheless.

As for the ‘Honourable’ East India Company, it was profiting from the ruined lives of as many as 12 million addicts in China alone.14 By 1833, the senior member of the Board for Customs, Opium and Salt, in charge of the booming illegal opium trade from India, was Sir Charles D’Oyly. After the Governor-General and the Bishop of Calcutta, he was the next highest-ranked man in Bengal. He had tied his career to the Company’s infamous opium trade without, it seems, the slightest prick of conscience, and had grown his own private fortune from their generous wages. His years at Patna were spent surrounded by poppy fields and opium factories, yet he had contrived as an artist to avoid including them in his landscape paintings and sketches. You can say of D’Oyly that he was of his time, but ‘his time’ was already aware of the tragic consequences of opium addiction. The devastating impact of the drug on China and Indonesia in particular, did not seem to trouble him at all.

For small operators like Captain Carr, the challenge was to make the return voyage to England from Australia profitable by finding other sort-after goods to trade at Canton for silver and tea. On an earlier voyage Carr had discovered the tortoiseshell being bartered in the Torres Strait. The supply was limited, however, so he wanted to keep it a secret if possible. The Malay trading praus would have been a bigger threat to his income than the merchant ships of rival British traders. Five months after he had written it, Carr finally delivered his letter to the English-language Canton Register and it appeared in its 16 February 1836 edition. ‘GENTLEMEN,’ it began, ‘I beg you will make known to the public, and those connected with the vessel mentioned below, the following circumstance.’ Carr then went on to give the details of his visit to Mer and his encounter with a white youth and child. ‘I thought it right to make this known to you, to act on the information as you may think proper,’ he concluded. ‘I shall also write to London by the first opportunity.’ The editor of the Canton Register published his letter with the following comment: